![]()

1 Introduction

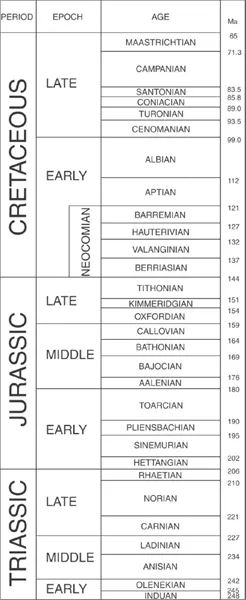

1.0. Geological time scale of the Mesozoic.

Modified from Palmer and Geissman (1999).

THE EVOLUTION OF MAMMALS DURING THE AGE OF DINOSAURS (IN the Mesozoic era; see figure 1.0), which encompasses 160 million years (Ma), or more than two-thirds of all mammalian history, was for a long time poorly known, with intriguing mysteries surrounding their origins and the relations among the different groups. Among the first to sort through this history was George Gaylord Simpson. In his first monograph on Mesozoic mammals (Simpson 1928a), he re-described most of the British Mesozoic mammals that had been collected since the middle of the nineteenth century and that are housed in the British Museum (Natural History) in London (now the Natural History Museum). His book also contained descriptions of some cynodonts (tritylodontids), which were at the time regarded as mammals. A year later, he published a second large monograph devoted to the Mesozoic mammals of North America (Simpson 1929). It was valuable work, but new discoveries were already beginning to alter our view of early mammals.

Simpson’s work contained no account of the significant material being uncovered in the deserts of Mongolia by the American Museum of Natural History’s Central Asiatic Expeditions (see chapter 3). Between 1922 and 1930, five expeditions to Mongolia brought back numerous dinosaur and mammal skeletons, as well as the first Cretaceous mammal skulls ever found. In addition to hundreds of articles and books on the scientific results of the paleontological expeditions to Mongolia, a number of popular or semi-popular books and articles were published in various languages, beginning with the great work of Roy Chapman Andrews, The New Conquest of Central Asia (1932).

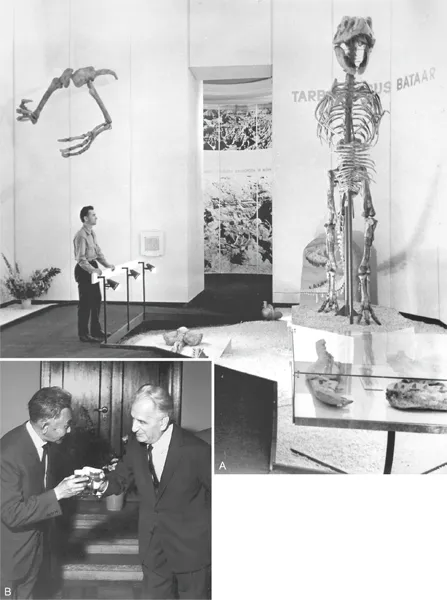

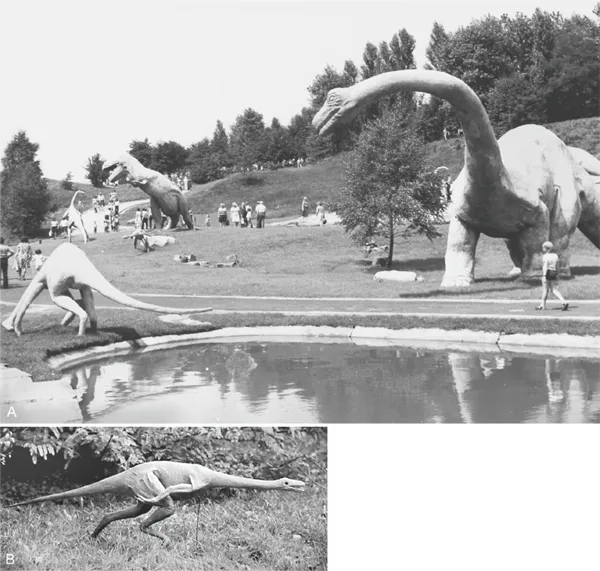

In 1930, and again after the Second World War, the Mongolian People’s Republic was closed to Western scientists, but paleontologists from Poland (a member of the Eastern Bloc) were allowed to work there. In 1963, I organized for the Institute of Paleobiology of the Polish Academy of Sciences the first Polish-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition to Mongolia. From 1963 until 1971 a total of eight expeditions were at work in Mongolia (see chapter 4). When the collections assembled by the first few expeditions arrived in Warsaw and were in large part prepared, the institute decided to show some of the prepared specimens to the public, and in 1968 opened the first exhibition in the Palace of Culture in Warsaw under the title Dinosaurs from the Gobi Desert (figure 1.1). Then in the summer of 1975 a permanent dinosaur exhibit opened in the Park of Culture in Chorzów (an industrial center in Silesia; figure 1.2). Subsequently, our institute opened in 1978 a permanent exhibit in the Palace of Culture in Warsaw entitled Evolution on Land.

1.1. A. Part of the exhibition Dinosaurs from the Gobi Desert, which opened in Warsaw in spring of 1968. On the right, the skeleton of a young individual of Tarbosaurus bataar, seen from the front, mounted in a semi-erect position; on the left, high on the wall, a cast of the shoulder girdle and forelimbs of a gigantic ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus. B. Roman Kozłowski (1889–1977) on the right, with Mongolian Ambassador Mr. Gurazhavyn Tuwaan, during the opening of the same exhibition in Warsaw.

Archive of the Institute of Paleobiology, Warsaw.

1.2. A. The first Dinosaur Park, open in Poland, at Chorzów in Silesia (southwestern Poland) in 1975. The models of dinosaurs were made at the Institute of Paleobiology in Warsaw, at the scale 1:10 by Wojciech Skarżyński and then enlarged to natural size by professional sculptors, on the spot. B. Reconstruction of a running Gallimimus bullatus in Chorzów Park.

Archive of the Institute of Paleobiology, Warsaw. Photographs by W. Skarżyński.

The Polish-Mongolian expeditions were of great importance for my work on the Late Cretaceous mammalian fauna, and I established many contacts with other workers in the field. One of these contacts proved to be particularly fortuitous. Beginning in 1965, I was in touch with Jason Lillegraven (figure 1.3A), who was working on his dissertation on the mammal fauna from the upper part of the Edmonton Formation in Canada (now referred to as the Scollard Formation). Since I had been working on Late Cretaceous mammalian faunas from Mongolia, we closely cooperated at that time. In a letter dated 1 March 1976, Jay announced that he and Bill Clemens thought the time was ripe for a new book on Mesozoic mammals and asked whether I would be interested in contributing a chapter on Asiatic Mesozoic mammals. I agreed with enthusiasm! During the next months our correspondence concerned mostly the details of the book and its chapters. I then accepted an invitation from the University of Wyoming to visit for six weeks in November and the beginning of December 1976 to work on editing our book. I spent the summer of 1976 in Poland in the cottage my husband and I shared in the small village of Zdziarka on the Vistula River some 60 km northwest of Warsaw hammering out on a typewriter (there were no personal computers at that time!) the chapters assigned to me.

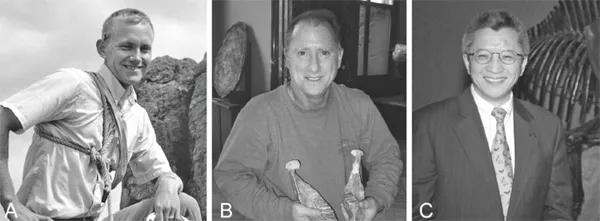

1.3. A. Jason A. Lillegraven as a student in 1964. B. Richard L. Cifelli. C. Zhe-Xi Luo.

During the autumn of 1976, typescript in hand, I arrived in Laramie, Wyoming, where Lillegraven had just settled into a new, large family house with his first wife, Bernie, and two small, charming children, Brita and Turi. And we began our work. In the preface to the book (Lillegraven et al. 1979), we described our rationale for the project: “The idea of this book developed through a course on the subject of Mesozoic mammals offered in the spring of 1976 in the Department of Geology of the University of Wyoming. Recognition by the students of: (1) the scattered nature of the literature; (2) the lack of recent general reviews; and (3) the fact that knowledge on Mesozoic mammals is expanding rapidly, led to the conclusion that it was opportune to provide a summary of the ‘state of art’ as of the late 1970’s.”

From correspondence with Jay, I had been led to understand that some of his students would provide descriptions of some groups of Mesozoic mammals. However, not much had been accomplished when I arrived in Laramie. It was evident that writing such summaries had been just too difficult for some students, and these chapters were not going to be written without contributions from paleontologists currently studying Mesozoic mammals. So we invited our Harvard colleagues Alfred W. Crompton and Farish A. Jenkins–specialists on early mammals–to write chapters on the “Origin of Mammals” and on the “Triconodonta.” In addition, William A. Clemens, one of the book’s editors, discussed with me the chapter on Multituberculata, which we decided to write together. He also agreed to correct the chapter on Symmetrodonta and become a co-author along with Michael L. Cassiliano, who originally had written this chapter (Cassiliano and Clemens 1979).

By the time I was ready to leave Laramie in December 1976, we had a more or less clear picture of how the book should be subdivided into chapters, whom we should contact as potential authors, and what more should be done. It was evident that we would need to meet at least once more. I invited Jay and Bill to Poland, and they arrived in Warsaw in the early spring of 1977. We packed all the literature we had on Mesozoic mammals and left for the cottage at Zdziarka to work for three solid weeks on our book. Beginning in 1977 Jay Lillegraven worked hard on the final editing of the book, Mesozoic Mammals: The First Two-Thirds of Mammalian History, which appeared in 1979.

In June 1981, the eminent Italian paleontologist Eugenia Montanaro Gallitelli (1906–1997), a specialist on fossil corals and micropaleontology, invited numerous invertebrate and vertebrate paleontologists from around the world to an international paleontological meeting in Venice, at which they presented papers on crucial problems of paleontology. I provided a lecture on “Marsupial-Placental Dichotomy and Paleogeography of Cretaceous Theria,” which, together with other lectures read at the symposium, was subsequently published in the book edited by Montanaro Gallitelli (1982).

In 1982 my husband Zbigniew Jaworowski, at that time professor of radiobiology at the Central Laboratory for Radiological Protection in Warsaw, received an invitation from the Centre d’Etudes Nucléaires in Fontenay-aux-Roses near Paris to come for a year to study the history of the contamination of the French population with heavy metals and radioactive elements. I took a one-year leave from the Institute of Paleobiology and joined him. Our stay in Paris was prolonged until August 1984 (see chapter 10 for a description of my work during our stay in Paris).

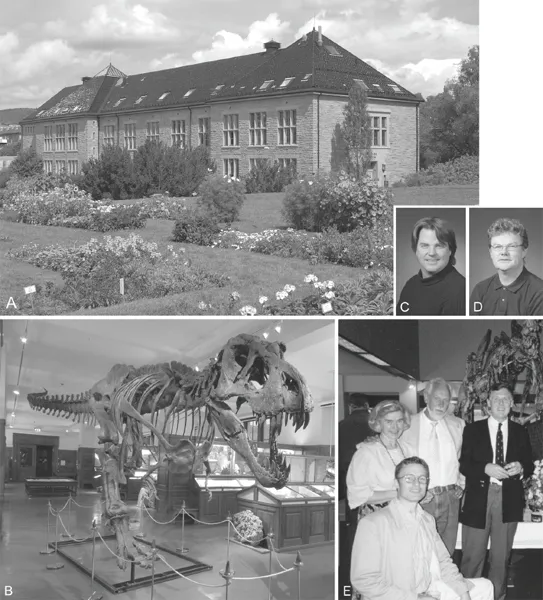

In the summer of 1985 I chanced to read in Nature an announcement from the University of Oslo calling for applications for the position of professor of paleontology. The situation of Polish science was at that time very difficult–there was no money for equipment and no funding for scientific literature or for traveling abroad. After a short discussion with my husband we decided that I should apply. In September, I sent my application with five boxes containing all of my publications, copies of my diplomas, and other necessary documents. The University of Oslo (figure 1.4) appointed a five-member international committee to assess ten candidates who applied from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Great Britain, and Poland. The committee completed its work in December 1986 and informed me that I won the competition. The nomination, in distinguished and beautiful regal style, signed by King Olav VI himself, was sent to me in January 1987. I was expected to take my position at the university by 1 June 1987.

My husband and I spent eight years and four months (1987–1995) in Norway (figure 1.4), where I received several grants from the Norwegian Science Foundation, which enabled my cooperation with colleagues from abroad, in particular with Russian paleontologists–the late Lev A. Nessov (1947–1995) and the Armenian Russian zoologist Petr P. Gambaryan (working in the Zoological Institute in St. Petersburg).

1.4. A. The building of the Mineralogical-Geological and Paleontological Museum in the Botanical Garden in Oslo. B. The cast of Tyrannosaurus rex mounted in a horizontal position of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae. C–E. Part of the staff of the Museum. C. Jørn H. Hurum. D. Hans-Arne Nakrem. E. Standing from left, Natascha Heintz, Kjell Bjørklund, and David Bruton; sitting, Bogdan Bocianowski.

A and B. Courtesy of Per Aas, Paleontologisk Museum, Oslo; E. Courtesy of Zbigniew Jaworowski.

During this time, the riches of the Gobi Desert were opened to scientists from the West when the political situation in European and Asiatic countries changed, beginning in 1989 with the Solidarity movement in Poland. The new political openness also resulted in invitations being extended to Mongolian paleontologists to exhibit Mongolian dinosaurs in the West.

As a consequence of one of these invitations, an exhibit entitled Dinosaurs et Mammifères du Désert de Gobi was set to open in Paris in 1992 (Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle 1992). My friend Philippe Taquet, at that time director of the Paleontological Institute of the Museum of Natural History in Paris, decided that the dinosaur displays would be more interesting if the dinosaurs were shown in association with the mammals that lived at that time. Two eminent French specialists on early mammals from the institute in Paris, Denise Sigogneau-Russell and her husband Donald Russell, visited me in Oslo at the beginning of February 1992. It was during that visit that Don, also a world-renowned specialist in preparing casts of minute fossils, produced copies of the Late Cretaceous mammals collected by members of the Polish-Mongolian Paleontological Expeditions. These casts were subsequently displayed alongside the dinosaur skeletons at the Paris exhibition. For the book released in connection with the exhibit, written by the staff of the museum in Paris in cooperation with Mongolian paleontologists based in Ulaanbaatar, Philippe Taquet contributed the section on dinosaurs (Taquet 1992), while Denise Sigogneau-Russell (1992) described the Mesozoic mammals.

A cooperative endeavor between the Mongolian Academy and the American Museum of Natural History led by American paleontologist Michael Novacek, a specialist on the evolution of eutherian mammals, and the late Demberlyin Dashzeveg, from Mongolia, began its work in 1990. In addition to numerous papers on the scientific results of the expeditions, Novacek published a charming popular book, Dinosaurs from the Flaming Cliffs (1996), describing the work of the expeditions.

In 1995, just before my husband and I were to leave Norway and return to Poland, David M. Unwin contacted me on behalf of the editors (M. J. Benton, M. A. Shishkin, D. M. Unwin, and E. N. Kurochkin) of the book The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia and proposed that I contribute a chapter on “Mammals from the Mesozoic of Mongolia.” I accepted but suggested that three other scientists, who in the last few years had contributed to the knowledge of Mesozoic mammals from Mongolia, join me as co-authors–M. J. Novacek, B. A. Trofimov, and D. Dashzeveg. My proposal was accepted, and I submitted our chapter in 1997. In 2000 the book was published by Cambridge University Press (Kielan-Jaworowska et al. 2000).

The last quarter of the twentieth century saw a remarkable accumulation of knowledge about early mammals. Mesozoic mammals have been discovered on all the continents (except Antarctica) and in regions where they had been unknown previously, for example, Australia and Madagascar. These discoveries include excellently preserved teeth, jaws, and parts of skeletons belonging to the groups that were formerly poorly known or unknown. In 1998, Richard L. Cifelli (figure 1.3B), from the University of Oklahoma, and I decided to write a new book on Mesozoic mammals. However, as both of us had been working mostly on Cretaceous mammals, it soon became evident that we needed a specialist on the earliest mammals and mammalian origins. We invited our colleague and friend Zhe-...