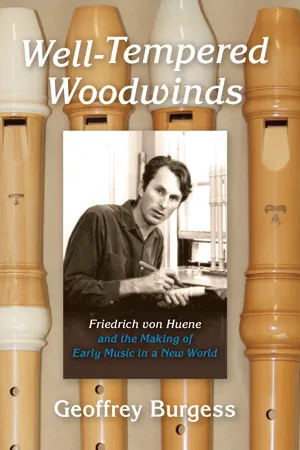

![]()

1Childhood in Paradise

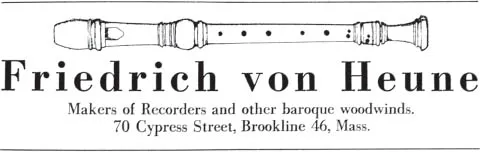

Figure 1.1. Advertisement in the American Recorder (1960).

HERALDED BY A HARPSICHORD

When Wesley Oler saw this announcement in the first issue of the American Recorder (February 1960) he wrote to von Huene excitedly: “It looks as though you are really in business!”1 The previous year, the Washington MD, recorder amateur, and collector encountered a von Huene recorder for the first time. The instrument was only the third that von Huene had made, delivered in June 1958 to the preeminent New York player Bernard Krainis. Oler immediately recognized it as the best recorder that could be had, and ordered one for himself. He quickly became one of von Huene’s most ardent supporters, and enthusiastically spread the word through the Washington chapter of the American Recorder Society (ARS).

Friedrich von Huene’s journey to this point in his career had been long and convoluted. It began on 20 February 1929 in Breslau (then part of Germany, now Wrocław in Poland). Only after escaping from East Germany, immigrating to the United States, attending college in Maine, serving three years with the U.S. Air Force, then completing college, and taking up an apprenticeship in Boston did he establish his recorder-making business in Waltham, Massachusetts.

Even if later in his career Friedrich’s stature among instrument builders was recognized with the title “Friedrich der Große,” few of his American customers suspected that, behind his charming affability and modest demeanor lay a noble heritage. His father, Freiherr (Baron) Heinrich Alexis Nikolai von Hoyningen-Huene, a Baltic German born in St. Petersburg in 1904, could trace his lineage back six centuries to knights who had taken part in the Livonian Crusade.2 His mother, Aimée Ellis (1903–1999), was raised in Hartford, Connecticut, and descended from Mayflower pilgrims. Both his parents appreciated music, and the night before Friedrich was born they attended a harpsichord recital given by Wanda Landowska.3 His mother sensed that Landowska’s music would bide well for her son’s future. Indeed, Friedrich’s career would not have been possible without the revival of the harpsichord and the interest in early music that Landowska and others had spearheaded. Fifty years later, when his reputation was well established and his workshop had graduated from the carriage house shared with the harpsichord builder Frank Hubbard, his mother once again recalled Landowska’s recital and Friedrich’s earliest experiments with sound. “It was Wanda Landowska I had heard the night before you were born and I remember when you were tiny and just standing in your crib and discovering that at a certain tone of yours, the lute hanging on the opposite wall responded with its own answer and your continuing delight over this miracle.”4

A BALTIC GERMAN BARON MEETS “MISS MAYFLOWER”

Friedrich’s parents had met in Paris a little under two years before he was born. Once married, they settled in Marburg, and then moved to Breslau for Heinrich to complete a degree in political science. His dissertation, which examined British-German negotiations prior to World War I, demonstrated his commitment to follow the path set by his father and grandfather by pursuing a career in international diplomacy.5 Emil (1841–1917) had been senior secretary in the Russian Senate from 1869, and in 1908 became a member of the Imperial Council’s Upper House, while Heinrich’s father Ernst (1872–1946) held a position in the First Department of the Directing Senate in St. Petersburg from 1896. With the establishment of the interim government after the Revolution in 1917, Ernst did what he could to expedite reform along democratic lines.

Like most Baltic German aristocrats, the Hoyningen-Huenes’ wealth was held in land. Their ancestors came from Westphalia in Germany and had settled in the Baltic States in the thirteenth century. By the sixteenth century Heinrich Hoyningen-Huene (b. 1597) was master of several estates in the Kurland area around Riga in present-day Latvia, and by the eighteenth century the family had acquired additional property in Estonia. At the end of the following century they moved freely between five estates and also kept a residence in St. Petersburg. Through Friedrich’s grandfather’s marriage to Countess Marie Sievers (1873–1958), the Hoyningen-Huenes acquired the 7,000-hectare (4,500-acre) estate Alt-Ottenhof in Livland (present-day Latvia). Close to the blue expanse of Burtneck Lake, Ottenhof became the family’s favorite vacation retreat. Heinrich, the third of five children, was particularly enchanted by the vine-covered house set amid lush green meadows, unspoiled streams, and magical woods scented with springtime lilacs and summer lindens. In addition to yachting, swimming, and hunting, music parties were fixtures during the family’s summer vacations. There would always be someone on hand to accompany their chorales, play four-hand piano duets, or entertain the children with rousing renditions of Finnish marches.

But by the time Aimée met Heinrich, the family had lost all its holdings in Russia and the Baltic States—at least temporarily. In 1917 Heinrich had witnessed a band of zealous revolutionaries break into their St. Petersburg home and apprehend his father and grandfather. After a short incarceration and interrogation by an ad hoc revolutionary tribunal, Ernst and Emil were released. While no one was killed, and the Hoyningen-Huenes sustained only limited damage, the Revolution had a serious impact on their lives. Fleeing to their estates would have placed them at greater risk, so they endured the harsh winter of 1917–1918 in their St. Petersburg residence with virtually no financial resources. Ernst lost his political appointment and took the only employment available—hard manual labor clearing the streets of ice.

Some months later, when Germany had taken the territory up to Riga, they escaped to Ottenhof where they could enjoy several months of peace. The end of World War I brought only temporary stability in the region. The Russians occupied the area, and by December 1919 the family realized that they would have to move on. Mindful of preserving what he could of family heritage, Heinrich rescued as many family portraits as he could, some of which now hang in his son’s home in Brookline. They joined relatives in Dresden, where they adopted a modest lifestyle. The lucrative income from the abundant harvests in their last years at Ottenhof evaporated in inflation. Ernst was forced to abandon his career as a lawyer and took a menial job at the Leo pharmaceutical factory. As consolation for the loss of Ottenhof he cultivated the small piece of land around their new home.

The family could also turn to music for solace. Heinrich’s favorite sister Margarethe, his junior by a year, had learned to play the piano in St. Petersburg and entertained the family with Schubert, Schumann, and Beethoven. Their limited finances did not allow them to attend more than the occasional concert, but they made a point of hearing the free vespers services with the Hofkapelle choir, and Margarethe sang in choral societies. Heinrich had no formal training in music, but through the Jugendbewegung (Youth Movement), he participated in the German folk music revival, and became interested in “early” instruments.

Having lived and worked in St. Petersburg meant that the Honyningen-Huenes were all fluent in both Russian and German, but they held to their German cultural identity and Lutheran faith. Religious ritual saw them through their daily life as well as their traumas. Ernst presided at daily Bible readings, prayers, and chorale singing, and family business transactions were likewise sealed with expressions of faith. Ernst had been educated at St. Anne’s School, St. Petersburg’s oldest German Protestant institution (established 1741). He later studied law and history in Berlin, where he was exposed to the principles of European constitutional government. His son Heinrich attended the König Georg Gymnasium in Dresden, where he mixed with young German aristocrats, but resources were lacking to fund his education further. Through a chance meeting with an American businessman who recognized his potential, Heinrich was offered a stipend to attend Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. During his studies in 1927 he enjoyed an active social life and made the acquaintance of the state governor, Theodore Francis Green, and a young actress called Hope Carey, both of whom would play significant roles in his future. His studies prepared him to serve as a European representative for the American’s business concern, the Nicholson File Company. Once he returned to Europe, Heinrich worked for the company briefly, and then, with the little money he had saved, enrolled in diplomatic studies in Paris.

It was through Hope Carey that Heinrich met Aimée Ellis. While he came from a large, noble, but impoverished family, Aimée’s background was more modest, and her family sparser. She had lost her mother when she was not quite three, and her father, always a distant and cold figure, died when she was in her early twenties. A plain girl with no particular achievements apart from a fair hand at sketching, Aimée was determined to escape her family’s expectations of a society marriage. Funded by trusts set up by her parents, she took herself to New York and enrolled in Bridgeman’s life classes at the Art Student’s League. City life opened her eyes to art, theater, and music. From New York, she planned to expand her horizons with European travel, and invited her school friend Hope Carey to accompany her. Together they set off, starting in Southern Italy and traveling north to Paris where Hope was eager for Aimée to meet Heinrich.

The two immediately sensed a mutual attraction, and after a short courtship they were engaged to be married. Their wedding in November 1928 was a fairytale pageant in Dresden’s Sophienkirche, followed by a honeymoon at Heinrich’s Aunt Margot’s château in Toffen, near Berne, in Switzerland. There they acquired some art works and family heirlooms, including the Baroque panels painted with commedia dell’arte figures that now decorate their son’s music room in Brookline. For the present, Aimée was the wealthy one. She came to realize that her American dollars, stretched thanks to the astronomic inflation in Germany, would be responsible for their livelihood, and she did not spare her generosity with gifts for the family and assistance for the essentials of life. Swallowing his pride, Heinrich learned to rely on the benevolence of “Miss Mayflower.”

Heinrich, whose charm was matched only by his audacity, invited two distinguished acquaintances to be his first son’s godfathers: Governor Theodor Francis Green, and one of his fellow students from the Dresden Gymnasium, Prince Friedrich von Saxe-Altenburg after whom Friedrich was named.6 Aimée and Heinrich planned a large family, and as they had both been brought up in houses with servants, they found a young nurse to take care of Friedrich. With the freedom this afforded them, they took a second honeymoon in Paris. There they had their photograph taken by Heinrich’s cousin George Hoyningen-Huene (1900–1968), whose iconic black-and-white photography had won him an influential position on the staff of Vogue (plate 2).7

Once Heinrich had finished his studies in Breslau, the young family moved on, this time to Berlin, where Heinrich hoped to find employment. They established their home in Wilmersdorf, known at the time as Little St. Petersburg because of the concentration of Russian émigrés. Berlin of the 1930s, captured so vividly in Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories, was the capital of power and decadence. But, with unemployment as high as 30 percent, life for many was desperate. Berlin’s nightclubs, alive with the rhythms of American Jazz, provided the chic and well connected with temporary respite from the disturbing reality that was overtaking the country. As he moved from one minor bureaucratic appointment to another, Heinrich got swept up in the hurly-burly and had more than one affair on the side, returning home “only to go like a whirlwind through the house and out again.”8 According to family lore, he provided the real-life model for the playboy Baron Maximilian von Heune (no doubt intentionally misspelled to avoid accusations of slander) in the cinematic adaptation of Christopher Isherwood’s novels, Cabaret (1972).9

Despite his infidelities, Heinrich resolutely believed in the sanctity of the family and the positive impact that Aimée had on his life. “I stand so firmly with you; you are the present, our children our future,” he wrote to her around this time.10 He also felt a deep longing to recapture the closeness to nature that he had felt at Ottenhof and convinced Aimée to look for a similar rural setting where they could bring up their family: a farm where they could produce their own food and combat Germany’s failing economy.

In June 1930, shortly after the birth of their second child, Michael (known as Maik), they joined the extended family at Ottenhof—the first return visit since their flight in 1918—for the baptism of their two sons (see figure 1.2). Ernst proposed that Heinrich and Aimée take over the estate, but Aimée felt that it was too isolated. It fell to Heinrich’s younger brother Georg to settle there with his wife and family, but only a few years later, in 1939, prior to the area’s being overrun by Stalin, they were forcefully relocated to the Hohensalza region of German-occupied Poland, and Ottenhof was irretrievably lost.

BLUMENHAGEN

In the spring of 1932 Aimée and Heinrich found a small farm 100 kilometers north of Berlin in the Mecklenburg region, in what would become East Germany. While dilapidated, it was affordable and had potential. With its languid undulation of hills, lake fringed with silver willows, and forests home to wild boar, rabbits, foxes, and deer, Blumenhagen was the substitute that Heinrich sought for Ottenhof. By the time they moved, a third child was on the way. Three daughters would follow over the next decade. For this growing brood, Blumenhagen was a paradise. Much smaller than Ottenhof (only 125 hectares, or about 300 acres), its varied landscape still provided much for the children’s entertainment. In summer, there was the lake for swimming and fishing, and little beaches for building sand castles. In the winter, fields of snow for building forts and the frozen lake for ice skating. Writing back to America, Aimée extolled the glories of her new-found Eden: “Deer and wild boar are h...