![]()

PART I

FROM SILENCE TO SOUND

![]()

1 | From the History of Graphic Sound in the Soviet Union; or, Media without a Medium |

Nikolai Izvolov

Translated from the Russian by Sergei Levchin

TYPICALLY, THE TERM cinema is reserved exclusively for moving images captured on a filmstrip by means of a photographic (i.e., positive-negative) process, capable of reproducing physical reality. Until now very little has been written about another, equally expressive and significant cinematic technique of the “optical period,” designed to synthesize a new and wholly novel audiovisual environment.1 Perhaps the most widely recognized name in this field of drawn animation is that of Canadian animator Norman McLaren, though he was neither the originator of this technique nor its sole practitioner.2

Notably, the possibility of this technique was never discussed in early theoretical writings on cinema. In 1945, one of the most insightful theorists of film, Béla Balázs, wrote: “Sound cannot be represented. We see an actor’s likeness on the screen, but never his voice. Sound is reproduced, rather than represented; it may be manipulated in some manner, but even then it retains the same reality.”3 Thus, the ontology of sound was equated with that of the voice or of music; no distinction was made between its acoustic and communicative aspects. One wonders whether Balázs’s actor was actually represented on film or merely reproduced there. This attitude seems especially perplexing when we take into account that Balázs collaborated on at least two films that made use of drawn sound.

There has been some writing on the subject of graphic sound, however, including S. Bugoslavsky’s chapter in the volume Mul’tiplikatsionnyi fil’m (The Animated Film) and a chapter in I. Ivanov-Vano’s Kadr za kadrom (Frame by Frame): unfortunately, neither offers more than a technical overview of the basic principles of the synthetic soundtrack.4 My own article, titled “Moment ozhivlenia spiashchei idei” (A Sleeping Idea Comes to Life), represented one attempt to set out the philosophical principles behind the idea of graphic sound.5

And so, who were the pioneers? Clearly, these could not be filmmakers—until the advent of sound, no one ever thought about sound theory. Instead, the most significant contribution to the invention and development of “drawn sound” was made by just four individuals: Arseny Avraamov (a composer and musical theoretician, and inventor of the forty-eight-tone universal musical system known as the Welttonsystem, or universal tone system; Evgeny Sholpo (an engineer and inventor who developed a device for the artificial performance of music); Boris Yankovsky (an acoustics engineer); and Nikolai Voinov (an animation cameraman).

Drawing directly on film stock opened up possibilities not just for the image track but for the sound track as well. The Soviet pioneers of graphic sound made the most significant contributions to the invention and development of this technique, also known as designed, drawn, paper, animated, synthetic, or artificial sound. With remarkable unanimity, all the early practitioners note the date of the invention as October 1929, even Yankovsky, who was not actually there to witness it. None of them claimed sole authorship of the idea, possibly because the first person to mention it casually in conversation was yet another cinéaste, animation director Mikhail Tsekhanovsky:

The three of us were sitting in the studio—myself, E. A. Sholpo, whom I had invited to be my assistant, and artist-animator M. M. Tsekhanovsky (the maker of the first Soviet sound animation film, “The Postal Service” [Pochta, Tsekhanovskii and Timofeev, 1929], based on the work of Samuil Marshak). With immense interest we were using a magnifying glass to examine the very first, fresh print of the soundtrack, still moist, which had just arrived from the lab.

Tsekhanovsky enthused about the beauty of the ornamental waveform traced on the film. He fantasized:

“Interesting, if you were to trace an Egyptian or ancient Greek design on the soundtrack—would we hear some hitherto unknown archaic music?”

Sholpo and I brought his fantasy back down to earth. As the ornament itself is strongly periodical in form, depending on its shape, we would hear only single tones of one timbre or another. Whether they would be “Greek” or “Egyptian” is hard to say, but there would certainly be nothing resembling a melody. . . .

But the word had been spoken. The idea of reproducing a synthetic, “artificial” soundtrack on the film strip with all its brilliant possibilities—this idea had taken firm hold of us all.

After the film was finished, each of us pursued it in his own way.6

With these words, an idea was born—that of writing predesigned phonograms directly onto a film soundtrack—opening up remarkable new aural opportunities, which all participants in the discussion would later realize.

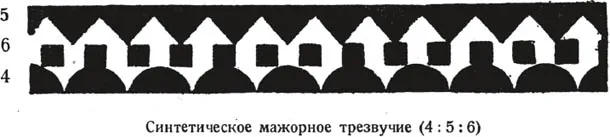

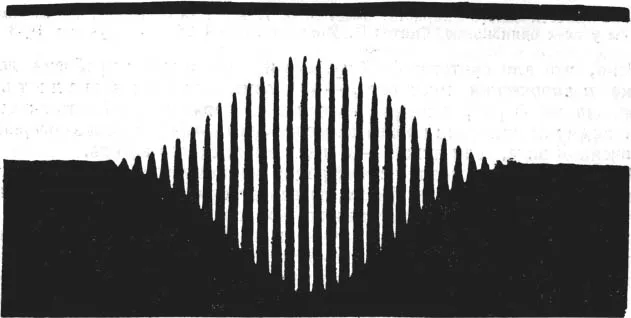

Figures 1.1–1.2. Illustrations to Arseny Avraamov’s article “Synthetic music,” Sovetskaia muzyka 8 (1939).

Unlike his three colleagues, Arseny Avraamov was not particularly interested in the technical side of the invention. Rather, he was attracted by the prospect of studying how visual forms could be transformed into the sound of music and voices. The underlying fundamentals of this process were the basic shapes of Euclidean geometry—squares, triangles, and circles—from which all visual forms are constructed, including those found on the optical soundtrack portion of the filmstrip (figures 1.1 and 1.2). Using the standard animation technology of the day, in the summer of 1930 Avraamov became the first person to create drawn sound; he demonstrated the results of his experiments at a conference on sound in Moscow the following autumn.

Each of the three remaining creators of drawn sound invented his own original device designed to facilitate the drawing of sound on film. Evgeny Sholpo called his the Variophone, though his colleagues at Lenfil’m Studios invariably referred to it as the Sholpograph in their various memoirs (figure 1.3).7 This device enabled the cinematic capture of sound on the moving filmstrip. Templates for the sounds were prepared on disks with the appropriate patterns cut into them. Depending on the number and configuration, the cuts could result in single sounds or chords. By means of prisms, a ray of light would penetrate the cuts on the rotating disks, which was reflected onto the film, which moved continuously (rather than spasmodically, as is more usual in film cameras). The disk could rotate at different rates relative to the film, thus producing various tempos.

Figure 1.3. Sholpo at work on the Variophone.

Interestingly, a mechanical television technology was also being developed at the same time: the Nipkov disk, which recorded and reproduced an image using a spiral pattern of holes. In response, Avraamov proposed another idea related to the reception of a television signal. If it was possible to transform an optical signal into sound, then the opposite must also be true: one could turn a sound signal into a visual representation. This hypothesis became the subject of his article “Sintonfil’m i Metamorfon” (Synthofil’m and Metamorphon). Though the “Metamorphon” proposed therein was never built, the idea of a rotating disk with openings through which light penetrates was nevertheless inherited from Sholpo’s Variophone (figures 1.4 and 1.5).

Figures 1.4–1.5. Illustrations to Arseny Avraamov’s article “Synthetic music,” Sovetskaia muzyka 8 (1939).

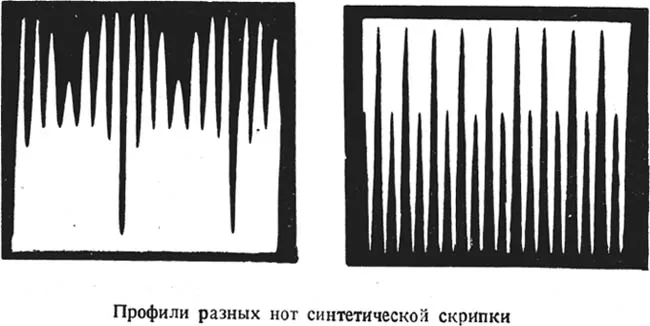

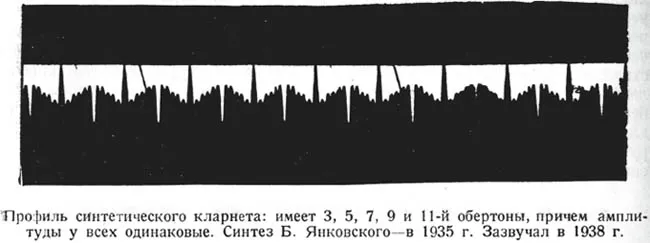

Boris Yankovsky’s device, the Vibroexponator, was devoted to creating sounds of varying timbres, a sonic aspect that had been largely underdeveloped in the other inventions (including those of Sholpo and Voinov). As a professional acoustic engineer, Yankovsky’s work in this field is particularly interesting and significant. From 1930 to 1932, he worked alongside Avraamov in his laboratory, conducting a great deal of research that would later prove essential for the graphic representation of sound. In 1932, the ambitious researchers announced that they were preparing to synthesize the sounds of human speech. Avraamov wrote that all consonant sounds could be conveyed in four types of graphic representations and that vowel sounds could be conveyed in only two. But this “homunculus” (as the idea was called by Avraamov’s colleagues) was not fated to be heard.

Nikolai Voinov, who also began his experiments with Avraamov, created a device to make a kind of paper “comb,” which could serve as a standard template for fragments of future phonograms.8 His method was based on the traditional technique of paper cutout animation. The soundtrack would be photographed alongside the image, frame by frame. This was a practical but restrictive method, as it reduced to a minimum the rich set of acoustic possibilities available to drawn sound. In the credits of the film Vor (Thief, 1934), Voinov’s method is credited as “paper sound,” though obviously the templates could have been made of any number of other materials. In contrast to the other inventors, Voinov was not inclined to theorize his approach, and did not leave any written texts. But his four finished cinematic works with designed sound have been fully preserved.

Unfortunately, most of the works by the inventors of drawn sound have not survived to the present day. Arseny Avraamov’s experiments were kept at his house and were accidentally destroyed. Boris Yankovsky’s inventions never left the laboratory stage and may have existed only in single copies. Nikolai Voinov’s films were much more fortunate. Some of them were released in theaters and exist in multiple copies. Four of his films are preserved in the Russian film archives. Probably the most well preserved archive is Evgeny Sholpo’s. Several dozen of his movies, along with fragments of those by other inventors, were shown for the first time at the animated film festival in Utrecht in November 2008.

By and large, the pioneers of graphic sound maintained friendly relations with one another on the basis of professional camaraderie and goodwill. Debates, when they arose, were mostly over theoretical differences. Thus, according to one legend, when the article “Na avantpostakh tekhniki” (At the Vanguards of Technology) appeared in the May 1931 issue of the journal Izobretatel’ (The Inventor) attributing the invention of drawn tone film (graphic sound) to Sholpo, and a few months later Soiuzkino recognized Avraamov’s contribution to the development of “graphic animated sound recording” using Sholpo’s technique,9 the composer was absolutely furious. On Sholpo’s next visit to Moscow Avraamov sought out the inventor and demanded an explanation. Evidently, Avraamov believed that Sholpo intended to take full credit for the idea of graphic sound. Fortunately, the matter did not come to blows, and the two men parted as friends.

One assumes that it was the relative minimalism of Voinov’s acoustic experiments that prompted the dismissive tone that is readily detectable in the writings of the ultra-sophisticated acoustic engineer Yankovsky.10 The group known as IVVOSTON (A. Ivanov, P. Sazonov, N. Voinov) was quick to respond in kind. The late A. Sazonov (son of P. Sazonov) told me about a decade ago that Yankovsky was an object of light mockery among the animators—though, having been very young at the time, he could not remember why.

He also recalled a remarkable incident...