![]()

PART 1

SOCIAL LIFE AND DEATH

![]()

ONE

Gold Coast Backgrounds

We were a people in motion still . . .

AYI KWEI ARMAH, TWO THOUSAND SEASONS (1973)

This chapter provides a historical optic through which the Gold Coast diaspora in the Americas can be better understood. If we can embrace notions forwarded by Gomez, Palmer, Thornton, and others that diasporic peoples carried their histories with them across the Atlantic, then understanding those histories helps contextualize the societies they encountered, confronted, and recreated in the Americas.1 Social death, then, may have been real and consequential. However, the forced separation of Atlantic Africans from the societies of their birth and their subsequent diasporic dispersals did not lead to mass amnesia nor, for that matter, a series of cultural holocausts. They did not forget the range of familiar political, social, and cultural geographies from their immediate pasts, nor could they continue their previous lives in unaltered forms. Physical separation from natal societies and life in chattel bondage in the Americas represented real historical watersheds and the frames within which the enslaved could engage in the invention and formulation of new sociopolitical traditions. Simply put, social death gave way to social resurrection as diasporic Atlantic Africans actively and continuously reinvented themselves using concepts with which they had strong familiarity.

In this view, the Gold Coast past mattered in their New World present. In order to grasp the processes of resurrection and reinvention in the Americas, Gold Coast backgrounds become key starting points for this study. The goal here, however, is not to project static conceptualizations of Atlantic Africa—histories without complexities, layers, and motion—or broad categories of continuities in the Americas. Instead, this chapter seeks to describe and understand the complicated and fluid “terrains”—physical, ethnolinguistic, and political—inhabited by diverse peoples throughout the early-modern Gold Coast with a particular focus on speakers of the Akan, Ga, Adanme, and Ewe languages. Within these ever-moving and shifting terrains, Gold Coast peoples and polities became linked through a number of ongoing political, commercial, and cultural processes. These connections, including the “Akanization” of Ga-, Adanme-, and Ewe-speaking polities by the early-eighteenth century and the spread of Akan—along the coast and into near hinterland regions—as a political and commercial lingua franca, resulted from identifiable historical processes and not from some ethereal sense of a shared or “genetic” Gold Coast or Akan cultural “heritage” existing in the region since time immemorial.2 Manifestations of cultural cross-fertilization, particularly the spreading influence and political domination of Akan-speaking peoples, meant that between 1700 and 1765 most of the Gold Coast Africans sucked into transatlantic slave trading vortices knew Akan as a primary, secondary, or tertiary language. This common linguistic thread and the heavy concentrations of Gold Coast Africans in specific Caribbean and mainland colonies in the Americas served as catalysts to ethnogenesis and the creation of Coromantee and (A)mina identities and cultures throughout the eighteenth century.

In sum, this chapter surveys Gold Coast history through the mid-eighteenth century. The northward expansion of the Asante kingdom during and after 1760 radically altered the ethnolinguistic composition of the Gold Coast slave trade as more and more non-Akan speakers were drawn into Atlantic commercial orbits. While some previous studies employ Asante-centric assessments of the Gold Coast slave trade and the formation of Gold Coast diasporas in the Americas, this bias toward the hinterland leads to underestimations of the number of Akan, Ga, Adanme, and Ewe speakers from littoral zones embarking on slavers during the early decades of the eighteenth-century—a period when Coromantee and (A)mina ethnic groups formed in the Americas.3 Since the larger study assesses the formation of the Gold Coast diaspora from the 1680s to the 1760s, limiting the chronological focus of this chapter allows for keener assessments of the links between littoral histories and geographies in the Gold Coast and the broader Atlantic World. In seeking to illuminate as much of the relevant and usable Gold Coast past as possible, the goal in this chapter is to recreate a part of the transregional history of eighteenth-century Atlantic Africa. As articulated by Kristin Mann, the diasporic paradigm employed here requires “a model that begins in Africa, traces the movement of specific cohorts of peoples into the Americas and examines how, in regionally and temporally specific contexts, they drew on what they brought with them as well as what they found in the Americas to forge new worlds for themselves.”4 From this frame, we can better judge and assess the nature of a range of continuities and discontinuities that became part of the multiple worlds inhabited by Gold Coast Africans in the Western Hemisphere.

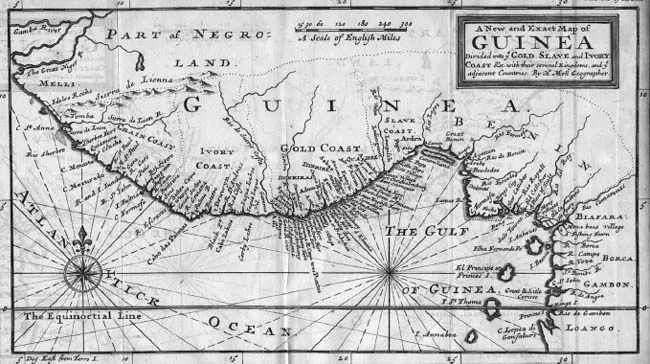

PHYSICAL AND ETHNOLINGUISTIC GEOGRAPHIES

No discussion of the Gold Coast can begin without some description of its physical terrain and topography. Historically, the area lacked a common place name among its inhabitants; the Gold Coast moniker was originally adapted by European traders in the sixteenth century from the Portuguese Costa da Mina (the Coast of Mines) due to the lucrative trade in gold in the coastal regions. The region includes just over three hundred miles of coastline in Atlantic West Africa situated between the Comoé River in the west and the Volta River in the east—encompassing parts of modern-day Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo. Depending on the century, or decade in some instances, the Gold Coast extended inland to the Volta basin in the north and—at least in terms of potential slave procurement or catchment areas—as far north as modern Burkina Faso. Much of the northern reach of the Gold Coast depended on the expansion and wide-ranging political influences of the Asante kingdom, particularly during the course of the mid- to late-eighteenth century.5

1.1. A map of Guinea divided into the Gold, Slave, and Ivory Coasts, circa 1680s. Source: Bosman, A New and Accurate Description, opposite 1. Courtesy of the Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Despite its small size relative to other coastal regions in Atlantic Africa, the Gold Coast was a land of stark contrasts. Within its diverse and shifting boundaries, the Gold Coast included three vastly different ecological zones—coastal grasslands, forests, and savannas. From south to north, flat coastal lands, salt marshes, and lagoons give way to hills, mountains, and dense forestation—representing a seemingly impenetrable “bush” in the early-modern European imaginary. In the view of Ludewig Rømer, a trader stationed at Christiansborg Castle in the 1740s, “Africa (the sea coasts excepted) is still wholly unknown,” a fact he blamed on “Nature herself,” which created thick stands of forest and bushes that even the inhabitants had difficulty managing. The land was not as foreboding and impenetrable as outsiders believed, though its tropical disease ecology—complete with such lethal afflictions as malaria and yellow fever—made the Gold Coast, and much of Atlantic Africa by extension, truly a “white man’s grave.”6

Despite its lethality to Europeans, the fertile coastal lands and inland savannahs sustained life to the degree that high population and settlement densities led to the wide proliferation of settled agricultural communities and large towns in the Gold Coast prior to 1600. On this note, Gerard Chouin and Christopher Decorse contend that as early as 800 CE, Akan-speaking peoples in the southern Gold Coast created a “pre-Atlantic” agrarian order in which they carved out—with iron tools no less—agricultural spaces and dwellings from the dense inland forests. Within these habitations, people cultivated palm oil and yam and used iron digging tools to create the entrenched earthwork settlements they lived in between 800 and 1500 CE. The Chouin-Decorse model is an open challenge to one forwarded by Ivor Wilks in which European contact and the start of Atlantic commerce in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries served as catalysts driving sociopolitical complexity in the southern Gold Coast. Joining and, for the most part, corroborating Chouin and Decorse in their counter to Wilks, A. Norman Klein introduced DNA and radiocarbon evidence that dates the presence of Akan-speaking agrarians in the forests of the southern Gold Coast by 700 CE. The pre-Atlantic agrarian order, however, collapsed abruptly as the possible result of epidemic disease that caused a demographic catastrophe and served a devastating blow to the rise and growth of polities in the Gold Coast when it struck. In the wake of rapid population collapse, a new “Atlantic agrarian order” emerged that coincided with the arrival of the Portuguese in the fifteenth century. In this case, the Gold Coast was still recovering from the demographic and sociopolitical legacies of epidemic disease, and the previous earthwork settlements and agrarian spaces of the pre-Atlantic agrarian order were largely reforested by the late 1400s.7

By the 1600s, both populations and agrarian settlements had rebounded. Indeed, the Gold Coast witnessed a veritable demographic explosion, perhaps as a result of the natural process of recovery from epidemic disease and not, as argued by Wilks, a new shift to crop cultivation. Wilhelm Müller, a Lutheran pastor residing at a Danish fort near Cape Coast from 1662 to 1669, described various “large and populous” towns in the region, including Efutu, Wimba (Winneba), Enkinne-Fu, and Ando-Crum. Reporting historical narratives passed on to him by the Ga-speaking residents of eighteenth-century Accra, Rømer noted, “The old Blacks tell us about millions of people once living on the Accra coast alone. . . . It was not only the coast that was densely populated. . . . where the mountains begin, [the district] was full of towns and people everywhere.” In sum, the Gold Coast was “full of people” in Rømer’s view, owing to a number of causes. “Blessed” and fertile land as well as efficient modes of agricultural production and labor mobilization combined to help sustain high population and settlement densities that later represented deep “recruitment” pools from which Europeans extracted enslaved Atlantic African labor.8

The peoples of the Gold Coast were just as diverse as the physical geographies they inhabited. The four largest ethnolinguistic clusters in the region, both numerically and in terms of geographic expanse, include Akan or Volta-Comoé (Fante, Twi, Guang), Ga, Adanme, and Ewe. These language groups were joined by a range of others—including Gur in the north and Etsii, Efutu, Eguafo, and Asebu in the south. Particularly in the coastal south, some of these smaller ethnolinguistic groupings became amalgamated by larger language clusters through complex processes of ethnogenesis, often as the result of military conquest or the political exigencies arising from the threat of northern invasion. In part, the current study seeks to work against the bias toward Akan speakers in historical accounts on the Gold Coast—Asante in the hinterland and Fante in the coastal south. Even if Akan speakers represented a numerical majority in the southern Gold Coast, they lived among and interacted with speakers of Ga, Adanme, and Ewe, and the resulting cultural formulations played out in revealing ways in the Western Hemisphere diaspora. In this specific sense, they created something in the Americas that went beyond an “Akan” diaspora, and both Coromantee and (A)mina were amalgams of the languages and cultures of a range of peoples living in the littoral and near inland regions of the Gold Coast.9

As John Parker notes, only a handful of historians “have paused to consider the history of the Ga-Dangme coast between Accra and the River Volta, yet it divides two of Africa’s most intensively researched cultural agglomerations: the Twi-speaking Akan kingdoms to the west, and the Aja- and Yoruba-speaking kingdoms in the east.” The lack of historical attention to Ga, Adanme, Ewe, and—to a lesser extent—Fante speakers in the central coast has a lot to do with the historical “weight” associated with centralized and expansionist kingdoms in Atlantic Africa—particularly Asante, Dahomey, Benin, and Kongo.10 Those who lived in decentralized societies and small polities constituted a majority of the people in the Gold Coast and throughout Atlantic Africa and, by the fact of their relative powerlessness vis-à-vis centralized kingdoms, they were overrepresented among the enslaved, the (dis)embarked, and the dispersed. It is for this very reason that their collective stories form an important aspect of the Gold Coast diaspora.

Before 1700, Akan was the most widely spoken language throughout the Gold Coast. It also had, by far, the largest geographic scope and spread. By the seventeenth century, the range for Akan speaking peoples encompassed much of the coastal portion of the Gold Coast, reaching northward beyond the region between the Afram and Volta rivers. From west to east, Akan speakers inhabited the area between the southeastern portion of what is now Côte d’Ivoire and parts of the coastal region east of the Volta River’s outlet into the Gulf of Guinea—in the western portion of modern-day Togo. Certainly, given the long history of human migrations and the rise and fall of powerful states throughout the Gold Coast, the region in which Akan speakers lived experienced constant expansions and contractions, rendering it difficult if not impossible to convey a sense of a stable ethnolinguistic geography. They, like others, were a people in continuous motion. Even the mapping of Akan-speaking habitation patterns in the seventeenth and eighteenth-century becomes more complicated when we take into account the Akanization of people from a variety of language communities conquered by Akan polities or through the more benign adoption of Akan as a political or commercial lingua franca. As a result of a number of intersecting political and sociocultural processes, many peoples throughout the littoral and near-inland regions of the Gold Coast were familiar with Akan or a mutually intelligible dialect and could likely speak it as a secondary or tertiary language by the early eighteenth century.11

Though many Akan traditions of origin speak of ancestors who descended from the sky or from under bodies of water, the corpus of “terrestrial” genesis traditions—in which the first people originated from underground—point in useful historical and archaeological directions. Due to the precision of the geographic locales at which Akan ancestors sprang from the ground, Wilks hypothesized that they represent the “exact sites where farming began” in the thirteenth or fourteenth century. Quite a number of these sites pointed the way to valuable archaeological findings producing some of the earliest known Akan materials, including ceramics and samples of charcoal. However, carbon dating pushes back the chronology from Wilks’s earlier estimates to 800–930 CE. These sites of Akan origins may have represented more than places where they began a new agricultural mode of production. In the “long memory” represented by Akan oral traditions, the sites where their ancestors emerged from the ground may have been geographic way points representing regions they settled after lengthy migrations from elsewhere.12 From afar, it may have seemed as if their ancestors emerged from holes in the ground, given how deeply rooted Akan speakers were to become in the forest fringe of the Gold Coast.

Using a fragmentary evidentiary base, a handful of writers—namely W. T. Balmer, Eve Meyerowitz, and J. B. Danquah—theorized that the ancestors of the Akan speakers who populated the Gold Coast originated from the ancient empire of Ghana. While this theory had a great deal of currency when the Gold Coast became independent in 1957—serving as the basis for the choice in name for the new republic—not much extant evidence supports the claim. Even more unsubstantiated have been the assertions of Akan connections to, in the words of Danquah, an “ancient heliolithic culture which once flourished in the Mediterranean and the Ancient East.” This particular theory originated with Thomas E. Bowdich in 1817 during the British mission to Kumasi—the capital of the Asante kingdom. In this case, Bowdich discovered what he thought were similarities between the laws and customs of ancient Egypt, Abyssinia, and nineteenth-century Asante. While orig...