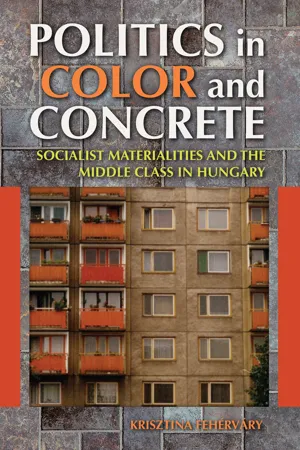

![]()

1 Normal Life in the Former Socialist City

The New Normal

In the mid-1990s in Dunaújváros, half a decade after the fall of state socialism, long lines once again formed in front of shops, but now for lottery tickets. An editorial on the front page of the local newspaper attempted to articulate the sentiments of the people standing in these lines, people still living in concrete apartment blocks, whose standard of living had declined rather than improved in the tumultuous years since the incursion of market capitalism.

Most people know…that unfortunately in this world it takes a lot of money for a full life. If you want to update your library, travel, see the world; if you want to have a livable home, drive a normal car, and occasionally have a respectable dinner—for these you need a small fortune. (Dunaújvárosi Hírlap, June 3, 1997)

Throughout my fieldwork, people used terms like “livable,” “normal,” and “respectable” to refer to services, goods, and material worlds that met their expectations of life after the end of state socialism. New telephone systems, automatic teller machines, twenty-four-hour convenience stores, and courteous sales clerks were amenities that many Hungarians associated with the dignity accorded respectable citizens of a “First World.” In contrast, they understood obsolete technologies and infrastructures, corruption and rude behavior, and the frantic pace of everyday life to be vestiges of a discredited socialist system. Scholars have reported similar uses of “normal” throughout central Eastern Europe and the Baltics during this period, as people used it to refer to things that were clearly extraordinary in their local context, but were imagined to be part of average lifestyles in Western Europe or the United States.

One could argue that such a normalizing discourse is precisely the mechanism by which older forms of consumption are replaced by newer, more elaborate forms. But that explanation forecloses a different set of questions: Why were such material environments and consumer goods normalized in these countries rather than explicitly marked as of European standard, as they were in Russia in the same period (Shevchenko 2009:128)? What functional and aesthetic qualities endowed certain places and things with such idealized normalcy, given that the ability to distinguish what counted as normal was not self-evident to outsiders like me?

The discourse of the normal indexed a profound adjustment of identity set in motion by the sudden geopolitical shift of these countries from Soviet satellite to aspiring member of a reconfigured “Europe.” Once envied within the Soviet bloc as the most western (and thus modern) of the socialist states, these nations suddenly found themselves situated on the undefined eastern border of greater Europe, with all the loss of prestige this entailed. After 1989 they were in the unenviable position of having to prove their westernness in a new context—to themselves as much as to a European Union reluctant to grant them membership. Hungary was disproportionately affected by this shift in status, having once been a popular vacation destination for residents of other Soviet bloc nations, who had regarded it as a paradise of freedoms and consumer affluence.

But closer attention to the Dunaújváros editorial suggests that the “full life” promised by winning the lottery was not a new desire and thus not one that can be fully explained by Hungary's entry into a global capitalist economy. While the imagined lifestyles of respectable citizens in Western Europe were certainly a model for the aspiring middle classes in Hungary, the full life referenced here is not one of mimetic transformation. Desire for high-quality comforts, conveniences, and health care, as James Ferguson (2002) has argued, is not the same as imitation and loss of cultural authenticity. It is a claim to membership in a wider society where citizens enjoy the tangible benefits of advanced technologies and economic prosperity. Qualities in material goods such as durability and functionality, innovative styling, and user-friendly or beautiful design were material evidence of the well-being that many people had long assumed their counterparts in Western Europe enjoyed. This well-being was made possible by a private life that ensured harmonious family relations, hard work rewarded with the means for dignified living, and a state that treated its citizens with care and respect. As we will see, “normal” materialities were regarded as signs of the emergence of a modern, civilized country, one that conferred citizens with the full humanity accorded to those peoples of coeval status with a First World (Fabian 1983).

In Dunaújváros, as elsewhere in the country, people used this discourse of the normal to evaluate changes to the material landscape after 1989, creating spatial and temporal distinctions between objects and spaces that seemed to be contemporaneous with the West and those that seemed caught in the quicksand of the socialist past. I begin by describing changes to Dunaújváros in the 1990s, providing a sense of how people responded to the changing world around them and how it met or failed to meet their expectations. I then turn to an examination of this discourse itself, including how it built upon two other, more enduring ways Hungarians evaluated material worlds and the kinds of people associated with them. One was a discourse of national identity that alternated between situating Hungary in Europe and “the West,” or positing it as an autonomous Magyar country whose authenticity stemmed from its eastern origins. Another was an equally long-standing set of discourses and norms for creating order (rend) in the material world. These three discursively explicit and morally loaded ways of evaluating the material environment will begin to ground what appear as conventional middle-class fashioning practices in the particularities of Hungarian history—and thus set the stage for the rest of the book.

A New Landscape

The regime change in Hungary catalyzed swift, ideologically motivated transformations to the built environment, most of them carried out by the first democratically elected nationalist government. The new regime focused on eliminating all symbolic references to the socialist state, communist ideology, and Soviet occupation in public space. As elsewhere in the former Soviet satellite states, the red stars that had graced all public buildings for four decades disappeared overnight. Statues of Marx and Lenin were removed, though some of these were later displayed, somewhat controversially, as socialist “relics” in a tourist-oriented park on the outskirts of Budapest (Nadkarni 2009). Ideologically charged street and place names such as Red Army Road or Lenin Street were literally crossed out, superseded by signs displaying names associated with presocialist Hungarian nationalism, apolitical names from the socialist era, or newly created names reflective of a nonsocialist Hungarian identity. In Dunaújváros, the city council named one street after Zoltán Latinovits, a beloved socialist-era actor, and another after Lajos Kassák, the famous modernist poet, writer, and artist. Elsewhere in Hungary, place names linked to heavy industry were generally equated with state socialism and replaced, but in Dunaújváros, names like Ironworks Avenue remained. For a time, I lived on Foundry Worker Street (Kohász utca) and noticed that when I gave my address to clerks in Budapest, they would snicker in disbelief.

As the streetscape changed, so did shop fronts and store shelves. Consumer goods once accessible only through trips to the West or through personal connections became abundantly available in shops, though access to them was now determined by raw purchasing power rather than by connections. The currency used to buy these commodities had also been transformed. Socialist-era symbols on bills and coins were replaced with grand figures from Hungarian history, including King István (Stephen), the founder of Christian Hungary at the turn of the first millennium, and Count István Széchényi, considered to be the founder of modern Hungary. The hefty weight and high quality of the new metal alloy coins, in contrast to the aluminum coins and flimsy bills of the socialist era, were designed to convey the substance and cultural value of European currencies—even as these were giving way to the euro elsewhere in Europe. These changes politicized places, buildings, and objects that had been for the most part, as Maya Nadkarni observed, “unnoticed facets of everyday life” (Nadkarni 2010:194–95).

In contrast to these rapid, largely symbolic changes, a more gradual unmaking of the material world of the socialist state was taking place through production of an aesthetically distinct built environment. The ground floors of city buildings, blackened by decades of exposure to pollution, were painted in bright colors to showcase small shops, restaurants, and boutiques with fanciful window displays, creating a bright commercial corridor for pedestrians. The renovation of one building on a soot-darkened city block sometimes threw the dilapidated state of neighboring buildings into stark relief. In the larger cities, new commercial spaces mushroomed, from postmodern bank buildings, luxury hotels, malls, and private medical clinics to big-box discount warehouses, gas stations, and convenience stores. Billboards, neon signs, and other forms of public advertising, which had been increasing in the last decades of state socialism, proliferated. The restoration of historic castles, churches, and cobbled streets was prioritized by both local and national governments. These artifacts of Hungary's presocialist past could be harnessed to transform the country's image abroad, de-emphasizing its role as ex-Soviet state and evoking its earlier status as part of the Austro-Hungarian empire.1 Meanwhile, the maintenance of socialist-era buildings, both civic and private, deteriorated as state funds evaporated and unemployment rates rose. This neglect heightened the distinctions between spaces marked as “socialist,” and therefore of the past, from those marked as part of the postsocialist present.

Many Hungarians also embarked on transformations of their domestic space. New neighborhoods of single-family homes emerged, contrasting with the apartment blocks that epitomized residential norms under socialism. Those unable or unwilling to make the sacrifices required to build such a house had recourse to interior renovations. In Dunaújváros, some people were only able to repaint their living quarters, but others showed me around new, open living spaces created by adding arched doorways and tearing down walls. Ceramic tiles in bright white or natural tones replaced linoleum floors. And the old, uniform front doors were replaced by doors of carved wood or padded leather or personalized with a brass nameplate. Although these changes were often not visible from outside, redecorating practices were publicized by ubiquitous advertising, specialty stores, television shows, and home decorating publications.

These new construction and renovation projects, undertaken at a time of great economic uncertainty, were often achieved at an expense far beyond a family's means. Nationwide, the average size of new houses was significantly larger than those considered comfortable by the socialist standards of the 1980s (122 square meters), and far bigger than the largest standardized apartments (72 square meters or about 700 square feet). Homebuilders and renovators sacrificed elsewhere in order to use the highest quality materials possible (Magyar Nemzet, Oct. 15, 1996), from Italian tiles, German appliances, and American floor heating systems to Hungarian porcelain sinks. And yet as I was shown around these newly transformed spaces, proud residents responded to my admiring exclamations by insisting, “Well, it's totally normal, isn't it?” (Hát, ez teljesen normális, nem?). I was bewildered by these reactions. In my experience in Hungary during the 1970s and 1980s, I had often been shown objects or spaces people had been proud of, such as an unusual belt buckle or self-built addition to a weekend cottage—and it had always been appropriate to admire such innovations and mark them as special. At first I wondered whether these statements were aimed at me, either to claim equivalent status with me or making assumptions about what I would think was normal for the United States. But I soon realized that this discourse of the normal was not limited to exchanges with or for the benefit of outsiders (cf. Herzfeld 1997). It was widely used in everyday conversation and in the popular media throughout most of the former Soviet bloc countries.2

System Change Comes to Dunaújváros

Given the rapid changes that followed the end of state socialism elsewhere in Hungary, I fully expected the system change to visually transform Dunaújváros equally rapidly, revamping the vast expanses of monochromatic apartment buildings with new colors and distinguishing forms. But in the early 1990s, other than the discreet iron bars on ground-floor windows and the rare outburst of graffiti, it was striking how little seemed to have changed. In fact, after 1989 new building of all kinds ground to a halt and the city became the physical embodiment of what Reinhart Koselleck has called the “one-time future” of a past generation (Koselleck 1985:5). Throughout the country in the 1990s, a common lament was the lack of a “vision of the future” (jövőkép) thought to arise from the past. In Dunaújváros, this was a problem of particular significance. Dunaújváros's origin myth as a new socialist city built on a modernist tabula rasa haunted its reputation and self-image. Unlike other towns in the country that had the material artifacts of a precommunist history in civic buildings, churches, and so forth, Dunaújváros had little upon which to build, little materiality of a valued past that could carry it into the future.3

By the 1990s, this town of 57,000 had spread out on a plateau on the western side of the Danube and could be divided into thirds. Multistory, residential apartment buildings covered one-third of the total area of about twenty square miles, housing 80 to 90 percent of its population (Figure 1.1). This was the main part of town, where the majority of apartments were two room spaces with a bathroom and small kitchen. A small neighborhood called the “Garden City” (Kertváros) was nestled in the midst of these districts of apartment buildings, where some families had been allowed to build houses for themselves. The steel factory and its grounds spread over the southern third of the new town, separated from the residential areas by a green belt. The final third consisted of the presocialist, run-down village of Pentele to the north, long ago incorporated into the city as the Old Town district (Óváros), as well as an area of single-family houses built over the last three decades of state socialism.

Dunaújváros residents were uncertain of how their city could manage the transition from stigmatized socialist showpiece to “normal,” capitalist city. The dairy factory closed in 1995 and the clothing factory the following year. The city hospital suffered the fate of medical health facilities throughout the country, namely massive funding cuts, which severely reduced the number of hospital beds and caused the flight of many trained staff, including doctors, to more lucrative private enterprises. Central to the uncertainty about the city's future was the fate of the largely state-owned steel mill (vasmű) employing more than ten thousand people in the mid-1990s, or almost a fifth of the city's population. By 1993, the unemployment rate in Dunaújváros had shot up from almost zero to 10.7 percent, though it had stabilized and begun to fall by 1995.

Figure 1.1. The two primary forms of buildings in Dunaújváros: in the foreground, a Socialist Realist residential block from the Stalinist 1950s; in the background, a high-rise “panel” building built in the 1970s. Visible in between are two five-story original concrete panel buildings from the early 1960s. Photo by author, 1997.

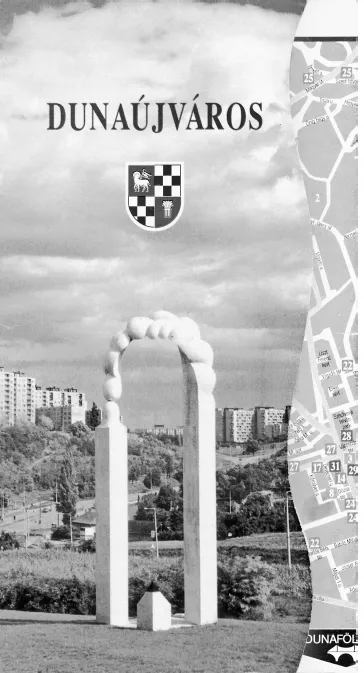

While many older working-class residents continued to identify with socialism, the elderly villagers in the old town of Pentele, most of whom were ambivalent about the new town, regarded the fall of state socialism as an opportunity. A “friendship circle” (the Pentele Baráti Kör) had been meeting once a month for years, sometimes for occasions such as a Hungarian song night (Nótaest). They wasted no time in constructing a memorial to the Pentele community members fallen in World War II who had never before been memorialized because they had fought against the Soviets. Next came a memorial to the two hundred local heroes who died in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, signaling the resurrection of a presocialist Hungarian history and the old village's place within it. The group commissioned an eight-meter-high braided arch of white marble from a local sculptor nationally known for his use of ancient Hungarian symbolism. Erected on a hilltop along the main road into the town, the arch provided a new entry, reframing the angular cityscape behind it (Figure 1.2). In the unveiling celebration, a prominent local artist declared that with this monument, “Finally, there is hope that this city can come to terms with its own past. That it can believe, and make others believe, that what was, is now past” (Dunaújvárosi Hírlap, Sep. 28, 1990).

Among the other visible changes to the city, some were literally made from the inside out, as apartment privatization gave residents the right to make alterations as long as they did not interfere with the structural integrity of the building. In the higher-quality apartments of brick construction in the city center, built during the Stalinist period, people had more leeway to take down walls and enlarge windows. Some were able to buy or appropriate the attic spaces in these buildings to create spacious loft apartments (tetőtér). The city had encouraged such loft building in the 1980s to offset the housing shortage, but had restricted its size and scope. The lofts built in the 1990s, in contrast, took up the space of two or three of the standard two-room apartments below them. The terraces, mansard eaves, and double-story windows of these dwellings offered visible evidence that some people were beginning to enjoy entirely different kinds of private living space.

The steel mill's short-term future was secured in 1994.4 Because it was the largest and most modern of Hungary's steel factories, the new reform socialist government decided to streamline and eventually privatize it. This development was enough to reassure foreign and domestic investors and allow the city government to initiate construction and reconstruction projects, even though a postsocialist version of downsizing had afflicted other city employers. It was then that the dramatic changes to the landscape in Dunaújváros I had expected in 1990 began to materialize. The city's aging symbols of a discredited modernist utopia now provided a muted backdrop for monuments to a new capitalist era: car dealerships, gas stations, banks, shopping centers, and several new churches. The designs, colors, and materials of these new structures highlighted their difference from the modernist architecture surrounding them. The Opel dealership and gas stations were painted bright yellow and blue. A new bank, clad in mirrored glass, went up next to an oval-shaped, multistory shopping complex, providing a sharp contrast to the large but faded modernist cubes that housed the socialist department store and national savings bank. As a socialist new town, the only churches in Dunaújváros had been in the old village, and the churchgoing population had been negligible. But by 1996, the support arches of an enormous cathedral, financed in part by German Catholics, rose to break the angular uniformity of socialist-era residential estates that surrounded it (Figure 1.3). Nearby, a Lutheran-Calvinist church of red brick with curving lines was being built in a Hungarian Organicist architectural style, another Western-financed effort that had targeted the socialist city as an ideal place to begin undoing four decades of “godless communism.” And, although fairly small, the city's Mormon temple was said to be the first in Eastern Europe. (This affected my fieldwork, as I was often mistaken at first for a proselytizer. Most people's only direct experience with Americans was with the “polite young men” who were regarded with sympathy and yet irritation for their unwillingness to leave once they got their foot in the door.)

Figure 1.2....