This is a test

- 390 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Steve Larson drew on his 20 years of research in music theory, cognitive linguistics, experimental psychology, and artificial intelligence—as well as his skill as a jazz pianist—to show how the experience of physical motion can shape one's musical experience. Clarifying the roles of analogy, metaphor, grouping, pattern, hierarchy, and emergence in the explanation of musical meaning, Larson explained how listeners hear tonal music through the analogues of physical gravity, magnetism, and inertia. His theory of melodic expectation goes beyond prior theories in predicting complete melodic patterns. Larson elegantly demonstrated how rhythm and meter arise from, and are given meaning by, these same musical forces.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Musical Forces by Steve Larson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Theory & Appreciation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Music Theory & Appreciation1

Introduction

Sometimes we ask “How does that melody go?” At times we might say that a melody “moves by steps and leaps.” Or we might talk about melodies “ascending and descending.” In fact, it is hard to think of words for describing physical motion that have not been applied to musical motion. So this book’s first question might be, “Why do we talk about music as if it actually moved?”

Sometimes music can make us laugh, cry, or want to dance. At times it might induce us to see or remember colorful shapes and images, to recall painful or pleasant episodes, or to experience all kinds of different feelings. In fact, music and emotion have long been described as intimately linked. So this book’s second question (to rephrase our first question only slightly and to shift from motion to emotion) might be, “Why does music actually move us?”

This book gives partial answers to both questions by showing some ways in which physical motion influences our experience of classically tonal music (music of the Bach-to-Brahms era as well as much jazz and popular music) and contributes to its meaning. (As noted in the preface, the theory of musical forces concerns the experience of certain listeners: those listeners of tonal music who have internalized the regularities of “common-practice tonal music” to a degree that allows them to experience the expectations generated by that music. When this book talks about “we” or “us,” it is talking about members of that musical culture.)

The central argument of this book is that our experience of physical motion shapes our experience of musical motion in specific and quantifiable ways – so that we not only speak about music as if it were shaped by musical analogs of physical gravity, magnetism, and inertia, but we also actually experience it in terms of “musical forces.” Part 1 (chapters 2–7) describes this theory of musical forces, and part 2 (chapters 8–13) summarizes the substantial (and growing) body of evidence that supports it.

Of course, writers have long discussed music in terms of the metaphors of motion and forces.1 But the theory of musical forces presented in this book takes five further steps. Although none of these is entirely unprecedented, their combination is novel. First, the book identifies and rigorously defines three melodic forces (“melodic gravity” is the tendency of notes above a reference platform to descend; “melodic magnetism” is the tendency of unstable notes to move to the closest stable pitch, a tendency that grows stronger as the goal pitch is closer; and “musical inertia” is the tendency of pitches or durations, or both, to continue in the pattern perceived) and two rhythmic forces (“rhythmic gravity” and “metric magnetism”; these are discussed in chapter 6, where the rhythmic aspects of musical inertia are also explored in greater depth).2 Second, the book embraces the metaphorical status of those musical forces as central to, explanatory for, and constitutive of both our discourse about music and our experience of music. In other words, although these forces may feel to us as though they are inherent in the sounds themselves, they are actually a creation of our minds, where they are attributed (consciously or unconsciously) to the music – shaping our thinking about music and our thinking in music – so that they become a part of what may be called “musical meaning.” Third, the book explicitly grounds the operation of those musical forces in the theories of Heinrich Schenker. Fourth, it shows that the musical forces provide necessary and sufficient conditions for giving a detailed and quantifiable account of a variety of musical behaviors (for example, the regularities in the distributions of musical patterns in compositions and improvisations, and the responses of participants in psychological experiments). Fifth, it finds converging evidence for the cognitive reality of musical forces from a variety of practical and experimental sources.

In order to clarify the claims of this book, it may also be helpful to say what I am not arguing. I do not claim that the account given here completely explains the roles of musical forces in our experience of music. I do not claim that musical forces completely explain musical experience. I do not claim that every melodic motion results from giving in to musical forces. I do not claim that musical forces have the same universality or “natural” status that physical forces do. I do not claim that such forces are an important part of every culture’s music. I do not claim that gravity, magnetism, and inertia are the only forces that shape melodic expectations. I do not claim that musical forces and musical motion are the only metaphors that inform music discourse and musical experience. And I do not claim that the ideas of pattern, analogy, and metaphor offered in this book give a complete account of human meaning-making.

A THEORY OF EXPRESSIVE MEANING

I suspect, however, that readers will want to think about how the idea of musical forces might contribute to a larger theory of expressive meaning – one that explains more thoroughly how and why music moves us the way it does. Therefore, in this introduction, I sketch the larger theory of expressive meaning in music that guides my thinking about musical forces. I do this in order to lay my cards on the table, as well as to contextualize the arguments of this book. But I do not claim that mine is the only possible theory of meaning that would encompass the idea of musical forces.3 I do not suggest that this book provides a complete description of that theory of expressive meaning. Nor do I believe that this book provides a complete defense of the value or the truth of that larger theory. Although the claims of this book may be seen as supporting that larger theory, they should be understood as claims about musical forces rather than claims about such a larger theory of expressive meaning in music. In other words, although this book makes claims about musical forces that could be understood as part of a larger theory of expressive meaning in music, I am not going to defend that larger theory – but I do want readers to see how the idea of musical forces might fit into such a larger theory. The theory of expressive meaning in music toward which my earlier writings point makes the following claim:

It is useful to regard part of what we call “expressive meaning” in music as an emergent property of metaphorical “musical forces.”

The remainder of this chapter clarifies what I mean by that statement – elaborating on the terms “expressive meaning,” “emergent property,” and “metaphor” – and it offers an overview of how some of these ideas inform the remainder of the book. Along the way it will be useful to respond to some of the objections that have been raised to this theory of expressive meaning.

Much has been written about emotion and meaning in music. In a book with that title, Leonard Meyer (1956) wrote that music excites emotions when it departs from what we expect. Others (e.g., Coker 1972; Cooke 1959; Davies 1994; Ferguson 1960; Kivy 1989; and Robinson 1997) have written about whether music can express emotions (or anything, for that matter), about whether music can “express” or simply be “expressive of” emotions, and about how musical meaning (if it exists) might differ from other types of meaning.

The theory of expressive meaning simply assumes that music has “expressive meaning” – that quality we experience in music that allows it to suggest (for example) feelings, actions, or motion. This quality may not translate well into words, nor relate clearly to the emotions felt by the creators (the composers, performers, and improvisers) of the music, but it seems to be one reason why we derive so much pleasure from listening to music. In other words, I use this term in the same way that Robert Hatten (1994, 2004) does and in the same way that Rudolf Arnheim (1974) uses the term “expression.”

Like Meyer, I also find an intimate connection between meaning and expectation. My theory further argues, however, that expressive meaning in music arises from the specific ways in which music moves when it denies – or confirms – our expectations. And I argue that we understand those specific ways of moving, in part, by using our knowledge of analogous physical motions – and the forces that shape those physical motions.

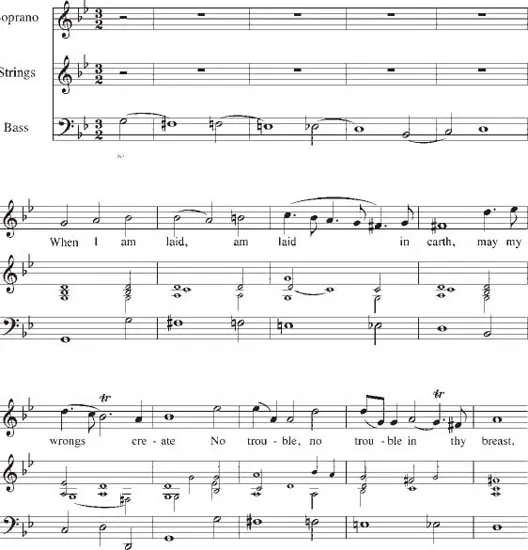

To illustrate some of the ways in which music can move us, and to help clarify the theory of expressive meaning in music, Examples 1.1 and 1.2 offer two types of musical examples. Example 1.1 gives the music for “Dido’s Lament” from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas – an example of a “lamento bass.” Example 1.2 (p. 16) gives a few excerpts that include what I call the “hallelujah figure”).

EXAMPLE 1.1. “Dido’s Lament” from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas.

TWO LAMENTO BASSES

In “Dido’s Lament,” Dido sings of how she would like to be remembered, just before she takes her own life. The music seems to capture the meaning of its text very well. It is based on a repeated bass line, the so-called lamento bass, which descends chromatically from tonic to dominant, in a minor key, and in a slow triple meter. A similar repeated bass line occurs in the “Crucifixus” from Bach’s B-minor Mass – which tells of Christ’s death. The lamento bass has a long history of association with texts expressing sadness and death (Williams 1997).

Why have these (and other) lamento basses appealed to their composers as an excellent way to set such texts? One answer to this question might be caricatured as “rote learning of conventions.” According to this argument, we first hear “Dido’s Lament,” then notice that the words are sad, and finally come to associate that sadness with that piece and its bass line. Later, when we hear another lamento bass, we think something like “Oh, this sounds like ‘Dido’s Lament’ . . . so it must be sad, too.” Although I do not deny that learning such associations is possible, I am convinced that this view of musical meaning leaves out something important.

CONVENTION AND CULTURE

One problem with assuming that all musical meaning relies solely on “rote learning of conventions” is that it seems to assume that the musical material is entirely arbitrary – that it is purely conventional. However, if the musical material were really arbitrary, then any association between material and meaning would be possible.

One reaction to this argument concerning associations between material and meaning is to believe that “musical association is culturally determined – symbolic – and that is why just any association is not possible.”4 This reaction is emblematic of a line of thinking that is counterproductive to the project of this book, so I examine it here at some length.

Note, first of all, that such a reaction makes an important point: culture does play a central role in helping to shape the associations we make between material and meaning. In fact, although the specifics of their claims have proven controversial (or at least thought, by some, in need of qualification), ethnomusicologists have noted relationships between culture, meaning, and musical material that seem to go beyond “rote learning of conventions.” Judith Becker (1981) has shown interesting connections between Javanese conceptions of time and the organization of their gamelan music. Steven Feld (1981, 1988) has discussed relations between the music of the Kaluli people and their stories about native soundscapes, as well as their habits of conversation. Alan Lomax ([1968] 2000) has suggested that, in folk songs from all around the world, correlations between attitudes about sex or authority seem to be reflected in aspects of a culture’s music (such as its vocal tension or textural organization). If these authors are right (and even if their claims need qualification), then culture does play an important role in shaping musical material and meaning.

At first glance, this reaction (“association is culturally determined – symbolic – and that is why just any association is not possible”) also seems to agree with at least part of the idea I am arguing for here: that it is not possible to make just any association between musical material and musical meaning. Nevertheless, this reaction implies that culture is the sole determinant of such associations (“association is culturally determined – symbolic – and that is why just any association is not possible”), and it describes those associations as “symbolic,” a term from semiotics implying that the association is arbitrary (more about this term in a moment).

THE SINGLE-MECHANISM FALLACY

Let us begin with three responses to the idea that associations between musical material and musical meaning could be determined solely by “culture.” These three responses concern single-mechanism explanations, the complexity of culture, and the logic of this reaction.

First, I am skeptical that anything as complicated as associations between musical material and musical meaning could be determined solely by any single mechanism – even one as complex as culture. Nevertheless, it is an interesting aspect of our minds (which seem to have a drive toward simple explanations) that they tend to seek causality in terms of a single mechanism. This idea (that our minds prefer to attribute meanings to single mechanisms even though mechanisms, including mental processes, tend to be multiple) is a recurrent theme in this book. For example, chapter 11 (“Evidence from Music-Theoretical Misunderstandings”) will re-examine single-mechanism explanations by noting that some prior writings about musical forces make an understandable but mistaken assumption: that only one force (whether physical or musical) operates at a time.

Second (or perhaps this just puts the same argument in a different way), if we understand “culture” in such a way that it is reasonable to regard it as the sole determinant of such associations, then culture must itself be a very complicated entity; that is, in this view, culture must surely include things like embodiment, body image, and body schema – factors that, as this book argues, reflect nonarbitrary relations between material and meaning.

Third, the logic of the reaction (“and that is why”) is not sound. Even if culture were the sole determinant of associations between musical material and musical meaning, it does not automatically follow that culture would therefore forge such associations arbitrarily. The reaction seems to suggest that if culture were the sole determinant of such associations, then the nature of the material would necessarily be irrelevant – that the nature of the material would not help determine such associations. The reaction implies that for any association that one culture might make between material and meaning, another culture could make apparently opposite associations – and that nothing about the musical material itself would make this improbable.

LEARNING, STATISTICS, AND INTERNAL REPRESENTATION

The reaction we are discussing raises an important practical question: “If associations are arbitrary, then how do we learn them?” In othe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- Part 1 A Theory of Musical Forces

- Part 2 Evidence for Musical Forces

- Part 3 Conclusion

- Glossary

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index