![]()

“Baba”

(Father)

Imi baba manyanya | Father, you are excessive |

Imi baba manyanya | Father, you are excessive |

Imi baba manyanya kurova mai | Father, you beat mother too much |

Imi baba manyanya kutuka mai | Father, you insult mother too much |

Munoti isu vana tofara seiko? | How can we, children, be happy? |

Isu vana tofara seiko? | How shall we children be happy? |

Kana mai vachichema pameso pedu? | While mother is crying in our sight? |

Kana mai vachingochema pamberi pedu ava? | While mother just keeps on crying in front of us? |

Vati ponda ako ndifire pavana vangu | Saying, “Kill me in front of my children” |

Ponda ako ndifire pavana vangu ava | “Kill me, let me die in front of my children” |

Tozeza baba | We fear father |

Vauya vadhakiwa | He has arrived intoxicated |

Tozeza baba | We fear father |

Baba chidhakwa | Father is a drunkard |

Tozeza baba | We fear father |

Vauya vakoriwa | He has arrived drunk |

Tozeza baba | We fear father |

Hoyi hoyi hoyi hoyi manyanya | Hoyi hoyi hoyi hoyi you are excessive |

Chavanotadza chiiko? | What is her offense? |

Chinomirira madhakiwa? | That he awaits her drunk? |

Idoro here rinoti mai ngavatukwe? | Is it alcohol that says to insult mother? |

Idoro here rinoti mai ngavarohwe? | Is it alcohol that says to beat mother? |

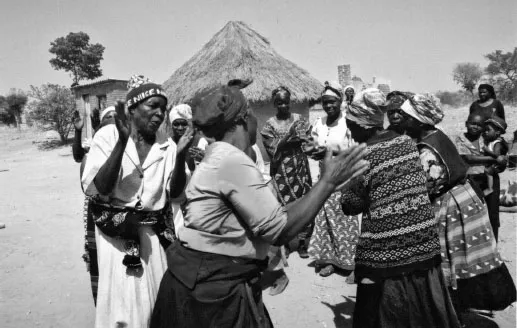

During the height of the dry season, in September 2002, I was invited to attend a postfunerary ceremony at my host family’s home in the Chiweshe rural areas, located along the way from Harare to Oliver Mtukudzi’s rural home, or musha, in the village of Madziva. Long relieved of their harvest, fields crackled with the parched stubble of maize stalks waiting to be plowed into the soil. Cows grazed at leisure, ambling together in small herds peppered by the brilliant white flecks of cattle egrets. Against a backdrop of bare boughs, a few trees clung to a last scrim of leaves. Low on the horizon, the morning sun was already hot as we awoke the morning after the ceremony. Just out of its reach, small groups of women rested in the shade. Seated on handwoven reed mats, or rukukwe, they gazed out at the modest structures of a rural homestead—a round kitchen with its thatched roof, a few square, brick bedrooms topped by sheets of corrugated asbestos, a crumbling, roofless toilet block, and a grass enclosure for bathing.

Mostly madzisahwira (sg. sahwira), or ritual best friends, these women had spent three days assisting the residents of this compound with the ritual of kurova guva, held roughly a year after the death of a family member to reincorporate his or her spirit into the family’s ancestral lineage. After staying awake all night, most people had stolen away for some much-needed repose. Yet these female madzisahwira spontaneously rose again, forming a circle in the middle of the dusty yard. Their long skirts swung out behind them as they began the weaving, counterclockwise movements of mafuwe, a ceremonial genre associated with rainmaking.1 Clapping their hands to keep time, the women launched into song, their voices settling into a high-pitched, narrow range as the lead singer called out:

Zvemusha uno / What is happening in this home

The others immediately answered her with a unison refrain:

A hiye wohiye rava dembetembe / Reflects a state of disorder2

Pausing momentarily, several of the singers interjected exclamations—Hokoyo / Watch out!—as well as frequent ululation, or mhururu, a ritualized expressive form reserved for women.

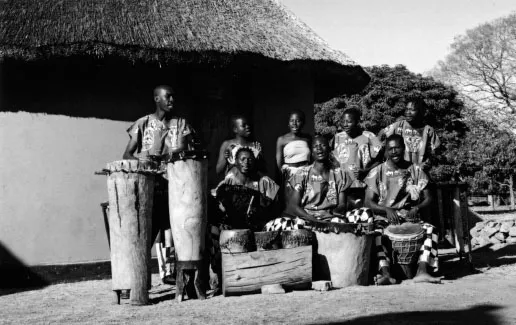

Soon, a group of men emerged from the house, carrying two drums, or ngoma. Throughout Southern Africa, several different varieties of ngoma share roughly the same construction technique. With cylindrical wooden bodies carved from whole tree trunks, their cow-skin heads, held firmly in place by a series of wooden pegs, can be struck with sticks or hands. From tall, slender instruments played while standing to wide, short drums capable of producing an incredible resonant bass sound, ngoma come in various sizes and can be played singly or in pairs. Depending on region, size, and genre, ngoma are known by an astonishing variety of names, even within Zimbabwe: mhito, dandi, mutumba, mhiningo, usindi, and mbete-mbete are but a few.

The staccato timbre of wooden sticks on hide shattered the early morning as the drummers launched into the powerful, syncopated rhythms of mafuwe. Joining them, a hosho player performed a simple pattern on a pair of shakers made of dried gourds filled with canna lily seeds. While he did little more than mark each triplet grouping, the hosho’s rich spectrum of frequencies immediately added sonic density and thickness, filling out the musical texture of the performance.

Celebrating the successful completion of kurova guva, the women whiled away the time with this recreational performance of mafuwe. Their position in the yard, a secular space that contrasts with the sacred realm inside the thatched kitchen of the family home, symbolically separated them from the deep work of ritual, now already completed. Yet the women remained preoccupied by themes of kinship, sociality, and moral relations, situated at the very heart of kurova guva. Invoking the moral personhood of hunhu, the lead singer intoned:

Zvemusha uno / What is happening in this home

VekuChihota we / Those from Chihota

Vanga vachiti hakuna hunhu amai / They have been saying, “It lacks hunhu, mother”

In the performance of these madzisahwira, we see with particular clarity how ngoma enables contemporary Shona speakers to articulate, negotiate, and critique evolving social relationships, transforming experiences of disorder, loss, and disjuncture into the moral relations of hunhu. We also see the madzisahwira’s special license to perform social criticism, which is linked to a long-standing Shona institution of ritualized friendship known as husahwira. Together, hunhu, husahwira, and ngoma represent the type of local forms of social organization that anthropologist Claire Ignatowski has described as “rooted in, though not unchanged from, the precolonial past,” and which continue to shape the experiences of millions of people throughout Southern Africa.3

Women dancing mafuwe at a kurova guva ceremony in Chiweshe. Photo by Jennifer W. Kyker.

The Zvido Zvevanhu ngoma ensemble performing in Harare. Photo by Jennifer W. Kyker.

Hunhu, Husahwira, and Ngoma in Tuku Music

While Oliver Mtukudzi’s urban, popular music seems far removed from this rural, ritual setting, the very elements so foundational to this performance of mafuwe—the social ethos of hunhu, the ritualized friendship of husahwira, and the participatory aesthetics of ngoma—are precisely those at the heart of Tuku music. In this chapter, I illustrate how husahwira and ngoma are enmeshed with Mtukudzi’s approach to singing hunhu, forming an essential frame of reference in understanding how Zimbabwean audiences have imbued his songs with larger social and political implications. Throughout the chapter, I return frequently to the song “Baba,” or “Father” (Shoko, 1993), which offers a representative example of how Mtukudzi has invoked the concepts of husahwira and ngoma in order to craft particularly vivid musical imaginaries of hunhu, enabling him to communicate more effectively with his audiences.

Houses of Stone

Before delving into these themes, I offer a brief overview of the political developments leading to Zimbabwe’s emergence as a modern nation-state, in order to situate my discussion of Mtukudzi’s music within a larger historical arc. Bounded by the Zambezi River to the north and the Limpopo to the south, the territory now known as Zimbabwe became a British Protectorate in 1891. After a series of uprisings known as the First Chimurenga failed to quash British ambitions, the colony was rechristened Southern Rhodesia in 1898.4 With a substantial settler population and the sort of extractive economic policies typical of colonialism, Southern Rhodesia was ruled by the British for the next sixty-five years, including a brief period of federation with the neighboring colonies of Nyasaland (Malawi) and Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), from 1960 to 1963. Shortly after the federation’s collapse, Southern Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith unilaterally proclaimed the colony’s independence from Britain in 1965, largely in an attempt to circumvent the British Crown’s demand for a transition to majority rule.

Yet Smith’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence merely hardened the determination of emerging African nationalist movements. Foremost among them was the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), a predominantly Ndebele organization, and ZANU, a predominantly Shona group. Soon, the struggle for self-governance evolved into a brutal and protracted armed war, which became known as the Second Chimurenga. In a desperate attempt to quell the rising tide of nationalist power, Ian Smith formed a coalition with yet another nationalist movement, the United African National Council, in 1979. The nation was r...