![]() Part One

Part One![]()

2Analytical Preliminaries: Brahms’s Sonata Forms and the Idea of Dimensional Counterpoint

Before starting in-depth exploration of the quartet, it will be helpful to describe the theoretical framework that forms the basis for subsequent analytical discussion. My approach to the quartet focuses primarily on musical form as a road leading to the intersection of structure and expression. Form, however, is conceived from a perspective that is more inclusive than is often the case in either theoretical or musicological studies. A movement’s form consists of the total structure that emerges through a counterpoint of musical dimensions.1 These dimensions can include virtually any aspect of a piece’s sound world, but for convenience they can be reduced to three main categories: thematic design, key scheme, and tonal structure.

Thematic design refers to patterns of melodic ideas organized into phrases, phrase groups, and so forth up to the largest sections of a piece. Key scheme indicates the succession of harmonic areas that are tonicized across the main sections of the form. Tonal structure encapsulates contrapuntal and harmonic relationships revealed through Schenkerian analysis. It is important to note from the outset that, although it is convenient to speak of these three parameters as distinct, any given musical dimension can never be completely isolated from the others. To evaluate the function of thematic components, an analysis must at minimum attend to aspects of key scheme, if not also to articulations provided by tonal structure. It would be impossible, for instance, to group the melodic ideas of a sonata into first-and second-theme groups without the guiding hand of the exposition’s modulatory trajectory. At the same time, evaluation of the significance of a tonicization depends on information provided by the thematic dimension: a modulation to the dominant cannot normally achieve the status of a key area until it is articulated into a section by thematic components. Similarly, a convincing account of tonal structure requires sensitivity to all aspects of the foreground, not least thematic, motivic, and rhythmic-metric characteristics.

The interaction of thematic design and key scheme produces patterns of organization associated with traditional form theory—binary forms, ternary forms, sonata and rondo forms, and so forth. A source of great musical interest in Brahms emerges from the counterpoint of these dimensions with tonal structure. Among other insights, a Schenkerian perspective provides a basis to distinguish between a formal section’s tonal center and its main prolonged harmony or controlling Stufe. Although traditional discussions of form often conflate key scheme and large-scale harmonic progression, these dimensions are not necessarily coextensive.

It is crucial to recognize that keys are relational networks, not sounding entities. A tonal center is formed by functional relationships between chords, not by any single chord. This is what makes it possible for a passage to be in a key without necessarily articulating the key’s local tonic. Thus metaphors of motion such as “the form progresses from the opening tonic to the dominant of the secondary area” are better suited to harmonies than to keys.2 It is true that the governing harmony for a section is typically its tonic, but this is by no means the only possibility. A local tonic may not appear until well within a formal section or even until the section’s point of closure. In other cases the tonic might not appear as a structural harmony in root position, but instead may be represented by an inversion. And in extreme situations, it might not surface in any form. For Brahms as well as his Classical forebears, the multiple possibilities are available not only in developmental passages but also in expositions, as alternatives to more conventional coordination of key scheme and Stufengang. This is one reason why it is important to draw a distinction between a work’s key scheme and its tonal structure: the progression of Stufen provides an important component of musical form distinct from a movement’s key scheme.

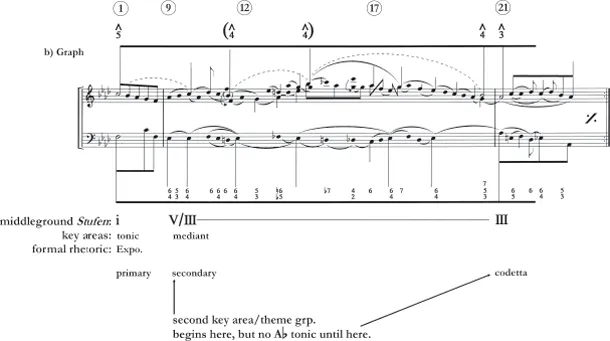

A brief yet beautiful passage from Mozart—the beginning of the second key area in the slow movement of his F-Major Piano Sonata, K. 280—illustrates all of these points (Example 2.1a). The passage encapsulates the essence of dimensional counterpoint on a small scale and thus lays bare the issues involved. It also demonstrates that considerations of dimensional interaction are crucial not only for interpretation of Brahms’s music, but also for the great tonal tradition of which he was a part. From the perspective of conventional formal analysis, the simultaneous entrance of a new thematic idea and a shift in key orientation from F minor to A♭ major articulate the movement’s secondary area at m. 9. In other words, the thematic and key scheme dimensions come together at this point to announce the beginning of a new formal section.

Yet, as the graph of

Example 2.1b highlights, the

position of the opening A

♭ sonority participates in a dominant rather than tonic prolongation. Indeed, Mozart delays the root-position A

♭ Stufe that more conventionally would enter at the outset of a secondary area all the way until the point of closure for the exposition (m. 21). Annotations beneath the graph highlight the lack of coordination between a traditional formal parsing based on theme and key and the middleground progression from i to III. A further layer of artistry arises out of the fact that the

chords throughout the beginning of the section project a double meaning. Because they contain the pitches of the tonic, they hint at the presence of the very harmony they participate in delaying.

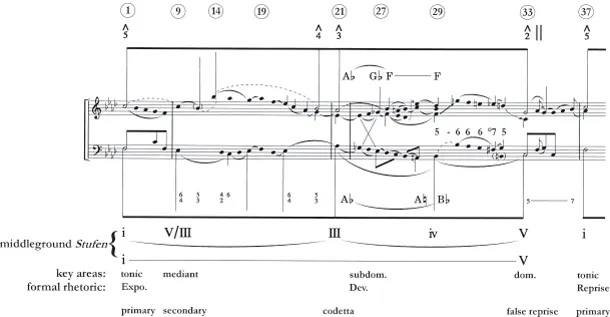

An analytic method sensitive to distinctions between key scheme and structural harmonic progression allows for greater responsiveness to the complexity of a passage like the Mozart sonata’s. We can at once observe ways in which the secondary area follows convention in the thematic and key-scheme dimensions, while also responding to the element of delay in the tonal structure—a crucial component of our aesthetic experience of the passage. Another advantage of drawing the scheme/structure distinction is that it allows for evaluation of the main harmonies of the key pattern according to their function in a large-scale tonal-contrapuntal framework. The middleground mediant at m. 21 in the Mozart sonata, for example, forms a stepping stone on the way from the tonic point of departure to the dominant that arrives toward the end of the development. Example 2.2 illustrates the coordination of this Bassbrechung with the movement’s sonata design.

Example 2.1. Mozart, Piano Sonata in F Major, K. 280, II

(a)Second Key Area

Although traditional formal analysis tends to treat tonicized harmonies as main pillars, a Schenkerian perspective dictates that not all tonicized chords are necessarily structural harmonies, and that not all structural harmonies are necessarily tonicized chords.3 Even if a tonicized chord is the main harmony for a formal section, it nevertheless may be subsidiary to other chords that form the pillars for a structural progression. This is the case in the Mozart movement, where the tonic and dominant have a deeper structural significance than the mediant, even though III governs a key area.

Example 2.1. (b)Graph

Example 2.2. Mozart, K. 280, Middleground Graph

Mozart emphasizes the dominant in this particular movement via tonicization at the false reprise of m. 33. Yet even if the dominant were never tonicized, it could participate in a high-ranking i–V progression. Because this point has been cause for concern among critics of Schenker’s approach, I will return to it later. For now, it suffices to say that the concept of dimensional counterpoint affords the opportunity to acknowledge the importance of key-scheme characteristics while still leaving room for the possibility of a Stufengang distinct from a succession of tonicized chords. An analysis thereby can respond both to a pattern of keys and to specific details of harmony and counterpoint through which a key scheme is articulated.

The importance of viewing Brahms’s forms through the interaction of thematic design, key scheme, and tonal structure is most easily demonstrated through a look at some actual music. My approach in this preliminary discussion will be to compare the first and last movements of the piano quartet with the first movements from the First Symphony and the C-minor string quartet. In addition to illustrating my analytical approach, the discussion will begin to present a formal overview of the piano quartet, as well as of two related works that we will return to in later chapters. The symphony and string quartet movements provide an appropriate context not merely because they are also C-minor sonata forms, or even because of the complex mix of similarities and differences among them and the piano quartet. They also, as already noted, share important expressive and biographical connections with op. 60: all ...