eBook - ePub

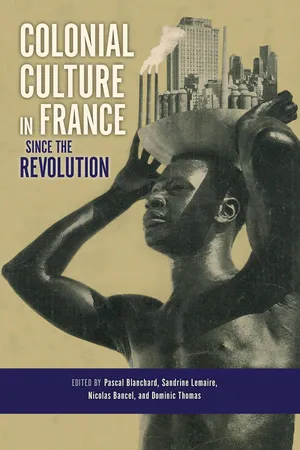

Colonial Culture in France since the Revolution

This is a test

- 648 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Colonial Culture in France since the Revolution

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This landmark collection by an international group of scholars and public intellectuals represents a major reassessment of French colonial culture and how it continues to inform thinking about history, memory, and identity. This reexamination of French colonial culture, provides the basis for a revised understanding of its cultural, political, and social legacy and its lasting impact on postcolonial immigration, the treatment of ethnic minorities, and national identity.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Colonial Culture in France since the Revolution by Pascal Blanchard, Sandrine Lemaire, Nicolas Bancel, Dominic Thomas, Pascal Blanchard,Sandrine Lemaire,Nicolas Bancel,Dominic Thomas, Alexis Pernsteiner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Afrikanische Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

GeschichteSubtopic

Afrikanische GeschichtePART 1

THE CREATION OF

A COLONIAL CULTURE

A COLONIAL CULTURE

Foreword

French Colonization: An Inaudible History

This foreword is based on a 2005 interview conducted with the historian Marc Ferro, a specialist on the issue of colonization and the reception of this past in French society, namely in books such as L’Histoire des colonisations (1994), Les tabous de l’Histoire (2002), and Le Livre noir du colonialisme (2003).1 He has described the current situation—a situation in which the French public has turned its back on the work of historians—as a form of “self-censorship by citizens,” paired with a “censorship by the governing authorities.” This sort of postcolonial posture, which characterizes France at the beginning of the twenty-first century, cannot and does not want to accept that “the Republic betrayed its core values” because to do so would be to question the “Republic” itself.

In his introduction to Le Livre noir du colonialisme, Ferro points to the “aftershocks” of this history today:

The events of September 2001, the shocks of Algeria, the demonstrations calling for repentance in France, are these not all the aftershocks of colonization, of colonialism? [ … ] At the dawn of the twenty-first century, before and after September 11, 2001, one notices that the sickness caused by colonization, which has been reincarnated in new forms—neocolonialism, globalization and accelerated globalization, multinational imperialism—affects both the territories and peoples formerly under European domination, and also the metropoles.2

Fifty years after the end of colonization, we must begin to inquire into the colonial aftershocks in the “metropoles,” along with what they mean for the field of historiography. The interview is thus interspersed with excerpts from some of Ferro’s recent work, to highlight not so much a “French taboo,” but rather a historical approach proper to the École des Annales.

The Republic Betrayed Its Core Values

Colonization was obviously a great scandal. The Republic betrayed its core values in Indochina and in Africa. Colonial peoples were never granted the full rights of citizens. Never mind the question of forced labor… But today there reigns a sentiment of “culpability,” which I find particularly striking, since a portion of public opinion acts as though this history had been entirely hidden from them. This is simply not true. It is just that previously it did not shock the sensibilities in the way it does today. Before, we were less concerned with human rights than with the Nation-State. At the time, people considered that the progress of “civilization” was at stake and that if we killed people, it was in the name of civilization!3

All those whose actions have put into question the legitimacy of their behavior— in terms of moral, ethical, and cultural norms—have a difficult time with the writing of their history. It took the Germans twenty years to produce serious books on Nazism. Only today do the Polish acknowledge that they were just as anti-Semitic as the Germans during the Second World War. The Russians also have a complicated relationship with their history: a riot practically broke out in 1994 with the release of Nikita Mikhalkov’s film Burnt by the Sun, because in it he showed the complicity of Russians in Stalinist crimes. Societies are not fond of self-flagellation.

Similarly, when it comes to colonization, France also resists its own history. This is understandable, if we consider the extent to which the decolonization process was largely an internal issue. For example, in the 1950s, with the crisis in Algeria, anticolonialist groups spoke out against torture, the comportment of the army and political personnel overseas, the mobilization of military recruits to fight against a people struggling for their freedom—they were protesting our institutions. However, at the time, few asked the question “What do the Algerians want?” Movements on the mainland rarely took up indigenous points of view, or considered what it was they were fighting for.

The fact is that the French did not have a firm grasp on Algerian political parties. They did not internalize the problems facing colonized peoples. Moreover, anticolonialist movements in the metropole turned a blind eye on crimes committed by these victims. In a way, for these movements, terrorist acts and crimes perpetrated in the name of liberation were legitimized by the simple fact that they were committed by these victims. Instead, they were more vocal about French repression in Algeria, which is to say the repression of terrorism, than with terrorism itself. While these issues were once taboo, they are being reconsidered today. Terrorism attacked institutions and killed innocent people, either in a random fashion or as part of a violent political policy seeking to liberate Algeria that even went so far as to target Algerian civilian populations. Quite clearly, this was a fact that the French did not wish to reckon with.

Furthermore, it would be wrong to hold the French army solely responsible for violence during this conflict, for the colonial system generally, and the Europeans who had been living in Algeria for some time, shared in this responsibility. These blind spots all contributed to the way in which the writing of this period took shape, as well as to the specificities of collective memory.

“History’s Taboos”

Today, we have developed the habit of using the word “taboo” for all situations. For example: “Torture during the Algerian War used to be a taboo.” No. It has often been evoked. [ … ] The topic was censured for a time, sure, then there was a long silence on the matter, and finally various events brought the issue to the fore. In Algeria, before the war, people spoke of the “mistreatment” of “Arabs”; meanwhile, the “Algerian problem” was indeed a taboo subject in many circles.4

In fact, this taboo even put into question the French presence in Algeria. The manner in which colonial history is taught in schools is absurd. It is broken down into two periods: “Conquest and Colonization” and “Independence Movements.” The continuity between the two periods is never established. Moreover, there is a clear effort to “uproot” the idea that colonization could have been criticized from as early as its very inception.

Let us again consider the case of Algeria to better understand the situation. There, autochthonous uprisings against colonization existed at every stage. By “cutting history into slices,” to cite Fernand Braudel, we make it impossible to understand colonization in its totality. Today, colonization is understood only through the prism of “torture in Algeria.” We have thus bracketed other traumatic facts: the massacres that took place in Madagascar, the carnage in sub-Saharan Africa, to name just a couple. Moreover, this is a simplistic vision of colonization that strips the overall situation of its complexity. Simply put, it is an abbreviated and false perspective.

One could compare it to textbooks in Japan, in which almost everything is false, for their aim is to legitimize the imperial tradition. Even in today’s Japan, it is extremely difficult to revisit this history, for the elites have all been brought up on these apologetic visions of history. In France, when it comes to colonization, the situation is analogous, which makes a more complex approach to colonial history rather difficult, even though anticolonialism is one of the oldest families of thought in this country.

Self-Censorship by Citizens and Censorship by the Governing Authorities

All of these facts [abuses of power in the colonies] were known, public. However, if denouncing them put into question “France’s actions,” then their existence was categorically denied: the government can make mistakes, but my country is always right… This conviction, internalized by the French, still exists today; it survives because of self-censorship on the part of the people and because of official censorship: for example, none of the movies or television programs “denouncing” the abuses committed in the colonies figure on the list of the 100 greatest hits, either in sales or in audience ratings.5

Today, there is a lot of talk about colonial history. It has become an important topic. Several major events have made this possible, notably the fall of communism, which led to a reevaluation of the nation-state and, through a ricochet effect, of “imperialist policy.” Indeed, the ideology of the nation-state, which was still a dominant ideology in the period between 1950 and 1970, has since ceded the ground to an ideology of human rights.

It is essential to understand that during the colonial period, the aspects of colonization that appear so scandalous today were still considered acceptable. A few decades ago—from the colonial period until about the end of the 1960s— colonial history was for the most part taught in textbooks, and though they were euphemistic, they did not hide the truth when it came to violent acts. However, these violent acts were not considered problematic, since they were legitimized by colonization as an emancipatory project. There was almost unanimous consensus when it came to colonization: according to the dominant ideology of the nation-state, the colonial act was fully legitimate. We cannot forget this ideological context: today we are at another point in history, in which an ideology of human rights has supplanted that of the nation-state. We therefore see colonial crimes in a completely different light from before, when they were tolerated, and “tolerable,” as a means to the “ends” of colonization.

It is also worth noting the conspicuous absence of a history of immigration. Such a history could help us to better understand the historic depth of xenophobia, recorded since at least the sixteenth century. Integration also has a long history. Today’s receding state has given way to micro-communities, often formed around specific roots, around provinces, regions, and also—for immigrants— around shared nationalities or origins. All of this appears definitively disconnected from the expected outcomes of history lessons.

The General Public Is in a Structural Rut

“The real problem in the postcolonial period is the general public’s self-censorship. The public will not go to see a movie that speaks poorly of them, or of their fathers, cousins, country, army. The public prefers instead to see movies that glorify them.”6 Regarding scholarly research, let us take, for example, the reception of Le Livre noir du colonialisme in France. This book was fairly well received by the general public, but poorly received by the academic community. Historians of colonization had, in sum, the following to say: “What is Marc Ferro doing on this territory?” Many scholarly readers expressed reluctance toward the book, or outright hostility, especially toward the parts where I compared colonialism to totalitarianism, an idea that had not occurred to many historians. The problem is that many of these readers are overly specialized in a chosen field, subject, or country, and refuse to stray from these narrow confines. However, we can make progress only if we begin to work on different subjects, on different terrains.

For example, in Le Livre noir du colonialisme, I was surprised by the similarity in structure between two films: Le Juif Süss and La Charge de la brigade légère. In Le Juif Süss, either the Jew has to stay in the ghetto and remain contemptible, or he has to integrate himself and be considered dangerous. In the second movie, the idea is the same: either the Indian remains outside of colonial society and is contemptible, or he assimilates and becomes a threat. I thought to myself, “My! The Nazi mentality and that of the colonists had a lot in common.” This realization drove me to compare Nazism with colonialism, and it was this idea, which came from colonial history and its ghetto, that caused some jealousy within the field. In sum, it is absurd to separate colonial studies from postcolonial studies either in the countries that were colonized or in the former colonizing powers. I remain convinced that we cannot study contemporary societies without taking into account their colonial heritage.

In France, the Republican tradition makes of our country the embodiment of revolution, liberty, equality, fraternity, human rights, and civilization within a frame of colonial expansion. Because France was supposed to be the incarnation of these virtues, the world had its eyes turned upon her—France with her great history—and expected her to revolutionize the world. The various European countries were thought to look upon France with envy and the Republican regime was considered by the French to be a kind of inspirational model for other peoples. Those who were not French could only one day hope to become French. This is why, in the case of France’s colonies (for example, in Algeria), French nationality was only granted in small doses, as an ultimate reward. In other words, the Republican tradition upheld the notion that, deep down, colonized peoples only wanted one thing: to become full-fledged French citizens. This was certainly the case for some, but not for all.7

Notes

1. Marc Ferro, “Le colonialisme, envers de la colonisation,” in L’Histoire des colonisations, ed. Marc Ferro (Paris: Seuil, 1994), Les tabous de l’Histoire (Paris: NiL éditions, 2002), and as editor, Le Livre noir du colonialisme. XVIe–XXIe siècle: De l’extermination à la repentance (Paris: Robert Laffont, 2003).

2. Ferro, “Le colonialisme, envers de la colonisation,” 47.

3. Marc Ferro, “La République a trahi ses valeurs,” Les collections de l’Histoire, no. 11 (April 2001): 3.

4. Ferro, Les tabous de l’Histoire, 11–12.

5. Ferro, “Le colonialisme, envers de la colonisation,” 13.

6. Marc Ferro, “Le filtre de la fiction,” La Revue: Forum des images (2005).

7. Ferro, Les tabous de l’Histoire, 28.

1

Antislavery, Abolitionism, and Abolition in France from the End of the Eighteenth Century to the 1840s

Before getting to the heart of the matter, it is important to clarify the terminology: “antislavery” and “abolitionism” are not equivalent terms, even if there exists admittedly a continuity between the two. Strictly speaking, though one could not be abolitionist without being antislavery, there is a qualitative difference between one term and the other. Proponents of antislavery limited themselves, in a way, to a moral condemnation of slavery based on religious, ethical, and economic principles, but they did not envision a way out, nor the means by which a society founded on slavery might transform itself into one founded on free labor. On the other hand, abolitionism was a form of political engagement, in which was conceived a concrete means of abolition, and even the kind of society to be established once slavery had been eliminated.

The organization of a postslavery society became the main question for abolitionists, and all conflicts and disagreements arising in the subsequent period revolved around how to achieve this goal. I will therefore limit myself to distinguishing between antislavery, which laid the groundwork for the condemnation of a system, and abolitionism, which proceeded one step further by considering both abolition itself and its characteristics, as well as the means of transition from the age of enslaved labor to the age of free labor.

A second point of terminology must be addressed: what was an abolitionist with respect to a reformist? Nelly Schmidt published an important book on this theme, although centered almost exclusively on the nineteenth century.1 There was, however, a continuity between the eighteenth century and the nineteenth century in this regard: there were many colonial reformers during the Ancien Regime and in the first half of the nineteenth century, who for the most part adhered to a logic of maintaining slavery, and their actions and proposals were aimed rather at adapting slavery, not eliminating it.2 Most often though these reform projects faced considerable resistance from the supporters of the system, who almost always adopted an uncompromisingly conservative position. For them, the system of slavery formed a coherent whole, and any reform, even at the margins, would lead to its rapid destruction. On the contrary, abolitionists were concerned with the complete elimination of slavery and anticipated the future of the colonies without slaves.

There were certainly both “progressivist” abolitionists—they, in fact, were the majority—who envisioned abolition as a process, and “immediatist” abolitionists— long an isolated minorit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction: The Creation of a Colonial Culture in France, from the Colonial Era to the “Memory Wars”

- Part 1. The Creation of a Colonial Culture

- Part 2. Conquering Public Opinion

- Part 3. The Apogee of Imperialism

- Part 4. Toward the Postcolony

- Part 5. The Time of Inheritance

- Bibliography

- Contributors

- Index