![]()

1

Paleontology and Science: What Is Science?

Introduction

South America, the southern half of the pole-to-pole landmass named, according to the usual attribution, after the Italian merchant and cartographer Amerigo Vespucci—or, as convincingly argued by Lloyd and Mitchinson (2008), after the wealthy Bristol merchant Richard Ameryk, a main investor in Giovanni Caboto’s second transatlantic voyage—remains a territory full of interest, intrigue, and biological treasures. Artificially severed from the northern half by the Panama Canal, it extends from the tropics, where the marvelous Amazonian rain forest offers its biological diversity and chemical riches of trapped carbon, to the elevations and endless steppes of Patagonia, its tapered south that points at and nearly touches frozen Antarctica. From west to east, the assortment of landscapes includes the soaring Andes, followed in places by the Altiplano that so aroused past greed for silver and gold, and then descends into the low-lying eastern plains, where the fossils discussed in this book have mainly been found.

Despite this variety in habitats, latitudes, and altitudes, the great naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, better known as Comte de Buffon, claimed that South America lacked enough vital energy to yield true giants among its fauna. Indeed, the present-day fauna boasts no true megamammals, i.e., those for which body mass is given in tonnes (or megagrams, hence the term). Impressive as it is for a rodent, the capybara, at 60 kg, can hardly lay claim for membership in the same category as elephants and rhinos. Also of similar size are two xenarthrans (a group of mammals particularly characteristic of South America), the giant armadillo Priodontes maximus and the giant anteater Myrmecophaga tridactyla (both, sadly, of dwindling populations), for which the adjective applies only in comparison with their close kin, but not if placed side by side with hippos and giraffes. The largest South American mammal is the tapir, whose bulk (approximately 300 kg) is less than striking compared with bison. Among carnivores, the jaguar is the largest, but it cannot match other top predators, such as lions and tigers, respectively two and three times its size.

It was Charles Darwin himself who corrected Buffon: rather than absence, the reality for huge South American mammals is recent demise. Ten thousand years ago, an instant in terms of geologic time, South America was inhabited by a mammalian fauna so large, diverse, and rare that today’s African national parks would pale in comparison. Bears, sabertooth cats, and elephant-like gomphotheres lived alongside much-larger-than-extant 150-kg capybaras and oversized llamas. Horses roamed these lands and went extinct thousands of years before Spanish explorers reintroduced the domestic species. In addition to these relatively familiar mammals, there were also bizarre creatures only distantly related to modern forms, such as terrestrial sloths several meters in height when standing bipedally; completely armored glyptodonts, hippo-sized animals related to armadillos; the camellike macrauchenids; and the rhinolike toxodonts, weird yet strangely familiar in echoing the ungulate, or hoof-bearing, types common in North America, Africa, and Asia.

Thanks to the efforts of many people, both collectors who found and prepared the material, often in decidedly uncomfortable and in some cases outright dangerous conditions, and scholars who interpreted those remains, we have now resurrected them for our contemplation and awe.

Traveling today through the sparsely populated regions of South America, it boggles the mind to think that the plains and low hills were once filled by a fauna so grand that it was rivaled only by the dinosaurs in magnificence. But unlike these long-extinct creatures of the Mesozoic, the South American fauna is much closer to us in time and in the phylogenetic (or genealogical) relationships to living mammals, as well as being more abundantly preserved. It is therefore easier to understand the biology and infer the ways of life of these magnificent mammals; further, the extraction of genetic material from the more recent fossils is already being accomplished, in contrast to the currently impossible science fiction world of Jurassic Park. Perhaps even more intriguing is that some of these mammals coinhabited these lands with early Americans, who may, regrettably, have had a hand in their demise.

In this book, we deal with the life and times of these remarkable beasts, the adaptations they evolved, their origin and journeys, the ecology of those (not so) long ago times, and the possible reasons for their extinction. All these subjects are dear to paleontology, a discipline that claims its own place within science. Most people think of paleontologists as adventurous individuals dashing through remote areas of the world to find and dig out dinosaur bones. Although it is true that paleontologists need fossils to understand life of the past, their scope of knowledge and skills is broader than that required to unearth old dead things. Paleontologists usually receive broad training in both biology and geology, and they are generally equally comfortable in the field, deciphering the geology of the area under investigation, and in the lab, researching and describing the material they have collected. The latter in particular requires a wide knowledge of living organisms—how else could we hope to understand the way extinct animals appeared and behaved from the meager scraps we have left of them? This requires, among other things, an extensive knowledge of anatomy—it is no coincidence that many paleontologists also teach comparative anatomy in universities and human anatomy in medical schools.

Paleontology and science

Paleontology falls under the aegis of evolutionary biology, the scientific field that deals with the remarkable diversity of the organic world, past and present. The theory of evolution, the cornerstone of modern biology, includes the set of ideas explaining how and why evolution occurs. It is one of science’s most robust theories, supported by an impressive array of evidence. Surprisingly, it also happens to be among those scientific theories that the general public is least confident in. A recent poll among Britons, for example, indicated that fewer than half of respondents accept the theory of evolution as the best explanation for the development of life, with nearly 40% opting instead for some form of creationism—the set of ideas that rely on some sort of supernatural creator or designer as an explanation for the origin and diversity of life.

The situation in the United States is pretty much the same as in the United Kingdom. It seems incredible that one of science’s strongest theories should be viewed with such skepticism in such a scientifically and technologically advanced nation. Then again, some have cast doubt on the theory of evolution and voiced support for the teaching of intelligent design theory in U.S. public schools. This position was soundly routed in U.S. district judge John E. Jones’s 2005 ruling against Pennsylvania’s Dover area school board’s decision to insert intelligent design into the public school science curriculum. In one of the most stinging criticisms of creationism to date, Judge Jones noted the overwhelming evidence that establishes intelligent design as a religious view, a mere relabeling of creationism, rather than a scientific theory, and he condemned the “breathtaking inanity” of the Dover board’s policy, accusing some of the board members of lying to conceal their true motive of promoting religion.

Much of the public’s suspicion of evolution is the result of a consistent battle waged by a small, but politically active and well-connected fundamentalist religious faction that has tried to disparage evolution while trying to impose its own viewpoint on U.S. public schools; that is, on students during what is probably their most intellectually vulnerable stage. Originally a concern mainly in the United States, creationism has taken root in other Western nations over the last two decades. Its onslaughts on science have both contributed to and played upon, in synergistic fashion, the general public’s misperception of what science is. It is one thing when people who have not received a higher level of education are swayed by creationists, especially as many people start out their school careers already inculcated with some worldview that includes elements of creationism. It is quite another when the more highly educated members of society (U.S. polls indicate about 40% of college graduates do not believe that humans evolved from some other mammals) and indeed a former leader of the nation—a Yale University graduate with any number of highly qualified advisors supposedly at his disposal—misunderstand science. It is even worse when many professional academics venture into a field not their own and, with an embarrassingly limited understanding of the subject (remedied by even a first-year university-level course), decide they are qualified to hold forth on the perceived inadequacies of evolutionary theory. To place this sort of dabbling into perspective, image an evolutionary biologist trying to set a nuclear physicist straight on real or imagined inconsistencies in the theory of quantum mechanics due to interpretations over the value of particle accelerators. It is so preposterous an idea that we wouldn’t even take its proposition seriously. Yet we must wonder why so few eyebrows are raised when (rather than if) the reverse happens.

There seem to be two main reasons why so many people have an aversion to evolution. One is that evolution happens to touch on aspects of humanity dear to many of us: our place in this universe, and the meaning and purpose of our lives. The centrality of these facets leads many of us to assert that our personal convictions are as equally valid explanatory tools as evolutionary theory in dealing with the diversity, development, and history of life on this planet. However, this is simply not true. Evolutionary theory analyses the physical and behavioral changes in the forms of life over time and provides explanations for how those changes occurred. That such changes have occurred is beyond any reasonable doubt. Opinions on such questions are not equally valid, any more so than is any particular person’s opinion on whether matter is really composed of atoms or the earth revolves around the sun. There may still be people somewhere in the world that believe in a flat earth. Their opinion, bluntly put, simply does not count. Evolutionary theory does not deal with, nor does it purport to deal with, questions of spirituality, which, for reasons explained below, are outside the realm of science. Many scientists, including a good number of evolutionary biologists, such as Francisco J. Ayala (Fig. 1.1), have reconciled religion and science, maintaining their spiritual faith while recognizing the fact of evolution.

Another reason why people mistrust evolution has to do with how they view science. This calls into question the effectiveness and role of science education in much of Western society. Science education has made great strides in the last half century or so, particularly in conveying scientific knowledge. Yet we have to wonder whether our emphasis on presenting the results and successes of scientific investigation has overshadowed the more basic principles of how we arrive at that knowledge, on what actually qualifies as science. If we have done our job properly, then by the time a student graduates from high school—given that we start science education in the elementary grades—the student would have a perfectly good grasp of what science is and what it is meant to do, and there would be little if any reason for debate on whether we can accept evolution as scientific or whether it is true or not because “it is only a theory, after all.” When almost half of college graduates—in the United States, at least—are confused, it might be a sign that we are not doing all we can as educators. Given the current level of misunderstanding about science in general, and to place the information of this book in context, it is worth spending a few pages to consider what science is.

1.1. Francisco J. Ayala in 2008, former Dominican priest and famed geneticist and evolutionist. Although he does not discuss his personal opinions, his views represent an appropriate way of dealing with science and religion.

Image courtesy of F. J. Ayala, University of California, Irvine, USA.

Science is so important to modern society that rarely does a day go by without a media report on some new discovery. It is perhaps because science is so ubiquitous that we have begun to take it for granted and fail to reflect on just what it is that’s behind the headlines. This is certainly one reason why science is so misunderstood, but the fact that so many people complete their formal education without understanding the fundamentals of science means that we may not be instructing students properly—or at least not emphasizing the essentials.

What is it about science that makes it so special? Most people view scientists as diligently working away to fill in some piece of a giant puzzle, a great edifice of knowledge that, once completed, would represent the truth about the way the nature works. This picture is misleading. Scientists are not out to seek some universal truth—at least, not in the way most people understand truth. At best, we can say that scientists are out to describe the way that nature works, and that the best we can usually do is to arrive at some approximation of the truth.

Science provides us with tentative answers. Any scientist worth his or her salt realizes that any answer is provisional and can expect to be corrected or revised (Tattersall, 2002). Eventually a larger understanding of nature’s workings is achieved, but this knowledge is always based on our current abilities to perceive nature. If new techniques or conceptual frameworks provide us with novel ways of analyzing phenomena, then we can expect our conceptualization of nature to change. This is precisely what happened when we switched our picture of matter and motion from a Newtonian to a quantum perspective.

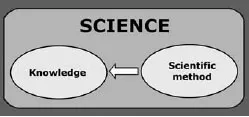

1.2. Science is a human activity that is both a body of knowledge (scientific knowledge) and a way (scientific method) of investigating natural phenomena. The method is peculiar to science and results in the knowledge we co...