eBook - ePub

The Year's Work in Lebowski Studies

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

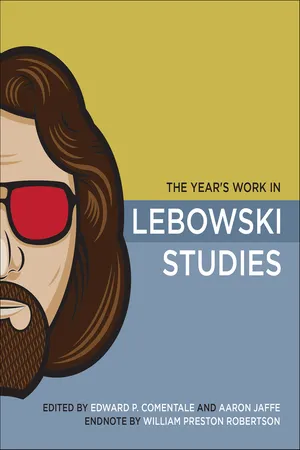

The Year's Work in Lebowski Studies

About this book

A massive underground sensation, The Big Lebowski has been hailed as the first cult film of the internet age. In this book, 21 fans and scholars address the film's influences—westerns, noir, grail legends, the 1960s, and Fluxus—and its historical connections to the first Iraq war, boomers, slackerdom, surrealism, college culture, and of course bowling. The Year's Work in Lebowski Studies contains neither arid analyses nor lectures for the late-night crowd, but new ways of thinking and writing about film culture.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part1

Ins

(Intrinsic Models and Influences)

1

The Really Big Sleep:

Jeffrey Lebowski as the Second

Coming of Rip Van Winkle

At the conclusion of the Coen brothers’ 1998 film The Big Lebowski, the tale’s frame narrator, the Stranger, asserts, “It’s good knowin’ he’s out there, the Dude, takin’ her easy for all us sinners.” Most manifestly, Jeffrey “the Dude” Lebowski fits into the Jewish folk tradition of the schlemiel—the bumbling, charismatic character to whom things happen.1 Like the classical fool, the schlemiel’s “antirational bias,” as Ruth R. Wisse has written, “inverts the rational model underlying so much of English humor, substituting for it a messianic or idealist model instead” (51). The Dude’s bias is directed foremost against effort. Things happen to him because he is not the sort to make things happen, his priority being instead the stylish avoidance of societal expectations—employment, marriage, even hygiene—that might interfere with “takin’ her easy.” By placing this avoidance in the service of “all us sinners,” the Stranger explicitly figures the Dude as messianic. The Dude stands in for viewers who, on some level, would likewise like to forego responsibilities; he redeems our often-soulless bourgeois striving with his compelling, carefree sloth.

Given the American Western flavor of the movie’s frame tale, the Dude arguably serves as a national savior. Indeed, The Big Lebowski grafts the schlemiel template onto a classic American narrative tradition that has always countered the more mainstream rags-to-riches story, or, as the wheelchair-bound tycoon for whom the Dude has been mistaken would have it, the achiever story. Eschewing the effort required to obtain riches, a number of American heroes have remained perfectly satisfied with their rags. In this respect, The Big Lebowski reprises the classic American monomyth that Leslie Fiedler delineated in his 1960 study Love and Death in the American Novel: the perpetual-adolescent male evasion, via masculine companionship and determined leisure, of structured work and marriage and adult responsibility.2 Fiedler finds an ageless American credo in Huck Finn’s valedictory comment, “But I reckon I got to light out for the Territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she’s going to adopt me and sivilize me and I can’t stand it” (Clemens 229).

A strain of the American psyche has always sought deliverance from duty, and a subset of our fictions have always offered us vicarious identification with appealing characters who find a way to “do nothing with impunity.” In this role, Jeffrey “the Dude” Lebowski resurrects Rip Van Winkle.

As Fiedler points out, this tradition originates with Rip Van Winkle, slacker hero of Washington Irving’s 1819 short story of the same name. Rip is a beloved figure among the women and children in his neighborhood, primarily for the friendly charisma that comes with his “insuperable aversion to all kinds of profitable labour” (450). His dictatorial wife, on the other hand, incarnates stern domestic obligation. In one of Rip’s periodic escapes from her into the wilderness that borders his village, he encounters a dreamlike band of Dutchmen playing ninepins and drinking a liquor that puts Rip to sleep for twenty years. His awakening is treated as a rebirth. He returns to a village completely changed by the American Revolution, finds his identity at first doubted by the new generation of townspeople, learns that his wife has died, and is ultimately accepted and even “reverenced” by the village. Having reached “that happy age when a man can do nothing with impunity,” Rip becomes an admired and envied surrogate for those bogged down by real-world responsibilities. The story ends with a reference to the gin that precipitated Rip’s sleep: “it is a common wish of all henpecked husbands in the neighborhood, when life hangs heavy on their hands, that they might have a quieting draught out of Rip Van Winkle’s flagon” (459).

Both Rip and the Dude must suffer the slings of a Franklinian culture that tries to demand striving and achievement, a demand most forcefully embodied in Dame Van Winkle and the Big Lebowski, respectively.

A strain of the American psyche has always sought deliverance from duty, and a subset of our fictions have always offered us vicarious identification with appealing characters who find a way to “do nothing with impunity.” In this role, Jeffrey “the Dude” Lebowski resurrects Rip Van Winkle. In their comic ineptitude, both serve a critical function, exposing the sickness of a straight society premised on the Puritan work ethic—on the equation of self-realization with material accumulation and public accolade. More to the point, though, they provide simple and abiding wish fulfillment. In doing so, they address an underlying American concern as well, working to relieve our nagging fear that we are inextricably bound up in this system. To identify with the slacker hero is to deny, if only imaginatively, our complicity in the dehumanizing world of consumption and competition.

That world has become only more inhuman over the past two hundred years, and the early-1990s Los Angeles setting of The Big Lebowski reflects this in a way that Irving’s relatively benign colonial upstate New York tale cannot. The Coens move beyond Irving in the way they tell their story as well. Both are frame tales, introduced and concluded by colorful narrators who stand outside the action. Irving’s narrator playfully overprotests his tale’s status as a true story, and in doing so he exposes the frame, gently undercutting our willing suspension of disbelief.3 The Big Lebowski, however, in its celebrated collision of genres and the ultimate incoherence of its plot, completely, comically shatters its frame. More than “Rip Van Winkle,” then, the Coens’ text enacts formally what its hero accomplishes on the level of content. On both levels, The Big Lebowski offers us an imaginative redemption from the cultural, structural imperatives that work to constrain us.

In his 2006 book Doing Nothing: A History of Loafers, Loungers, Slackers, and Bums in America, Tom Lutz reveals the continuing relevance of “Rip Van Winkle.” In a study that treats Irving’s story in some detail and traces the idle-hero archetype up through contemporary film—Slacker, Clerks, Wayne’s World, Office Space, and, briefly, The Big Lebowski—Lutz explains, “From the slacker perspective . . . the classic work ethic . . . is a kind of emotional derangement, and loafing is the cure” (25). He points to Benjamin Franklin as the “invent[or] of the work ethic as we know it,” and calls Rip Van Winkle “the anti-Franklin” (58, 101). Forty-odd years before Lutz, Leslie Fiedler formulated Rip’s influence thus:

The figure of Rip Van Winkle presides over the birth of the American imagination; and it is fitting that our first successful homegrown legend should memorialize, however playfully, the flight of the dreamer from the shrew—into the mountains and out of time, away from the drab duties of home and town toward the good companions and the magic keg of beer. (xx)

With minor adjustments, Fiedler could be talking about the Dude here. In their respective flights from duty and “time,” Rip and the Dude share a remarkable number of similarities. In Irving’s case, of course, Rip’s primary avenue of escape is extended sleep. Both slacker and protoschlemiel, Rip does not seek out this sleep; it is visited on him by way of the drink he sneaks from the Dutchmen’s mysterious keg of gin. In other hands, such a serious lapse in consciousness might come off as a little dark. The text most often referenced as the Coens’ touchstone for The Big Lebowski famously uses “the big sleep” as a euphemism for death. When his former boss tells detective Philip Marlowe that maybe nothing can spare Marlowe’s client from grief “except dying,” Marlowe concurs, “Yeah—the big sleep. That’ll cure his grief” (Faulkner, Brackett, and Furthman 86). By contrast, Rip’s big sleep is a rest cure. While he is out, Rip’s domestic and foreign entanglements—a hyper-restrictive marriage and British colonial rule—neatly resolve themselves. And, unlike the fate envisioned for Marlowe’s client, Rip is allowed to wake up and enjoy a grief-free second childhood.

The Coen brothers’ treatment of the motif is, like Irving’s, tongue in cheek. In his book The Big Lebowski: The Making of a Coen Brothers Film, William Preston Robertson quotes Ethan Coen as saying their movie “affects to be noir, but, in fact, it’s a happy movie. It’s a comedy.” It is in this spirit that Ethan responds to a question about his and Joel’s writing process: “‘Well, you know,’ he shrugs. ‘We sleep a lot’” (98–99, 47). Although we never see the Dude actually sleeping, we do see him relaxing deeply, for instance, in his candle-lit bathtub and prone on the rug he has lifted from the big Lebowski’s mansion. Twice he is rendered unconscious, once from a slapstick blow to the head and the other time, à la Rip Van Winkle, from a comically doctored drink. The Coens use both occasions to introduce extended dream sequences in which the Dude plays out his anxieties over the things that are threatening his freedom—Maude Lebowski’s manipulations, castrating nihilists, what have you. Even these anxieties are presented humorously, though, and in the end the Dude survives his surreal ordeal and resumes a carefree life at the local lanes. Like Rip’s, the Dude’s big sleep is temporary and serves mainly to transport him through to the less stressful existence he is accustomed to. As viewers, we are as drawn to the Dude’s spots out of time as “the henpecked husbands in the neighborhood” are to “Rip Van Winkle’s flagon.”

1.1. The Dude pursues his ease.

In classic American fashion, the two protagonists pursue their ease geographically as well as temporally. Irving’s narrator, Diedrich Knickerbocker (a figure every bit as quirky as the Stranger), situates his action at the foot of the Kaatskills, “away to the west” of the Hudson River. Although Rip resides there in a “village of great antiquity” (449), at the time of the story this represents the edge of the American frontier. As a man happy to “eat white bread or brown, which ever can be got with least thought or trouble” (451), Rip invokes the mythic American pattern of westward movement away from the domestic power centers of the East, toward dreams of easy money or, in his case, simply ease. Significantly, when Rip wishes to escape the “petticoat government” of Dame Van Winkle’s home, he heads further west into the forested Kaatskills.

The Coens’ westward theme is more obvious. The Western, as a literary and film genre, is clearly invoked in the movie’s first words as the Stranger drawls, “Way out west there was a fella,” voiced over the Sons of the Pioneers’ version of “Tumbling Tumbleweed” and a shot of a large spherical tumbleweed being blown across desert. The scene shifts as the floating cinematic perspective, in the script’s words, “top[s] the rise” to reveal “the smoggy vastness of Los Angeles at twilight,” and we follow the tumbleweed through empty, night-time city streets and finally across the beach to the Pacific, the early-morning mountains of the California coast silhouetted in the background. The tumbleweed reaches the shore and then turns right to blow upward along the coast. Though geographically this would be north, the camera pans so as to place the mountains, like Rip’s Kaatskills, still to the viewer’s left—the west—of the shoreline. In fact, however, the Dude has no further west to go. Los Angeles serves as the terminus for Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier thesis from a century earlier, wherein the closing of the American frontier presages the end of individual autonomy as a primary feature of American life. Whereas Rip can escape into the woods, the Dude remains trapped in the massive electrical L.A. grid that the film’s opening sequence lingers on.

Within that grid, though, the Dude is every bit as directionless as Rip Van Winkle, as signaled in the last refrain of the opening song: “Here on the range is where I belong / Tumbling along with the tumbling tumbleweed.” It is their mutual indolence that most clearly unites the two figures as American role models, the Dude reincarnating what Fiedler calls Rip’s “scapegrace charm” (333). In Irving’s story, Rip is introduced as “one of those happy mortals, of foolish, well-oiled dispositions, who take the world easy” (451). For the Dude, these are words to live by: when he reprimands Walter for drawing a gun on an opponent during league play, pleading “just take it easy,” Walter responds, “That’s your answer to everything, Dude.” Rip, we are told, has “an insuperable aversion to all kinds of profitable labour” (450). The Dude can relate. Though he tells Maude Lebowski his “career’s, uh, slowed down a bit lately,” he admits to the cops investigating his stolen briefcase that he is unemployed, and we are given no indication throughout the movie that he seeks to alter that status. Irving’s Knickerbocker tells us, “if left to himself, [Rip] would have whistled his life away, in perfect contentment; but his wife kept dinning in his ears about his idleness, his carelessness” (451). The Coens’ script first introduces the Dude as “a man in whom casualness runs deep,” and the Stranger famously “plac[es] him high in the runnin’ for laziest [man] worldwide.”

As mentioned, in Fiedler’s formulation the hero is always a man, always fleeing the responsibilities most directly associated with mature romantic relationships. Yet if Rip and the Dude are not lovers, neither are they fighters. That these particular protagonists’ lack of conventional drive equates to a lack of masculine aggression is thrown into relief by the American wars that serve as the backdrop for the two stories. Rip, who “inherited . . . but little of the martial character of his ancestors” (450), sleeps right through the American Revolution. He shifts seamlessly from “loyal subject of” George the Third to citizen in the republic presided over by George Washington (457). Aggression is likewise lacking from the Dude’s cosmos. He provokes Walter’s derision by proclaiming his pacifism, but he seems unfazed by the Gulf War, a backdrop which all but drops out of the film after an early sequence depicting a televised George the First aggressively denouncing Iraqi aggression against Kuwait. Despite his professed past of “breaking into the ROTC” and helping pen the uncompromising original draft of the Port Huron Statement, the Dude avoids physical confrontations and ignores current events. In this he resembles Rip, of whom we are told, he “was no politician; the changes of states and empires made but little impression on him” (459). The wars in both texts come off as inconsequential and serve primarily to highlight the thematic war between aggressive American striving and passive American slacking. And though the achiever Lebowski insists that the deadbeat Lebowski’s “revolution is over” and that “the bums will always lose,” it is peaceful idling that prevails in the value systems of these two fictions.

Rip does, the narrative tells us, chafe under one type of government, and that is the domestic despotism of marriage. Women are often the enemy in Fiedler’s classic American fiction, and feminist readers such as Judith Fetterly have identified “Rip Van Winkle” as a primary offender. Irving via Knickerbocker does more telling than showing in his characterization of Rip’s wife Dame Van Winkle, calling her a “shrew,” a “virago,” and, twice, “termagant,” and making no fewer than seven references to her sharp scolding tongue in the story’s first two pages (450–52). Though not “routed” into the woods by a domineering wife, the Dude is equally allergic to domestic partnership, demanding of Jackie Treehorn’s rug-pissing thugs at the movie’s outset, “Does this place look like I’m fucking married? The toilet seat’s up, man!” Walter reminds us that the Dude “do[es]n’t have an ex” either. As the Dude’s primary partner, Walter brings Knickerbocker’s misogyny into the modern era, referring to Bunny Lebowski (whom he has never met) as “that fucking strumpet . . . this fucking whore. . . .” Fiedler claims that American novelists tend to exclude any “full-fledged, mature women” from their fictions, opting “instead [for] monsters of virtue or bitchery, symbols of the rejection or fear of sexuality” (xix). A film whose two most substantial female characters are Maude and Bunny Lebowski would not seem to challenge that criterion.

Evidence of the Dude’s dread of spousal responsibility climaxes just after his only sexual encounter of the film. When Maude explains to him that her yoga-like contortions on the bed are meant to increase her chances of conception, the Dude, now standing at the bar, sprays his suggestive-looking White Russian halfway across the room, stammering, “yeah, but, let me explain something about the Dude.” He is clearly unwilling to accept the duties of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One: Ins (Intrinsic Models and Influences)

- Part Two: Outs (Eccentric Activities and Behaviors)

- Endnote: The Goofy and the Profound: A Non-Academic’s Perspective on the Lebowski Achievement

- Works Cited

- List of Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Year's Work in Lebowski Studies by Edward P. Dallis-Comentale,Aaron Jaffe,Edward P. Comentale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Popular Culture in Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.