![]()

Part One

![]()

I

Epilogue

Bloomington, Indiana, 1948–1993

My brother and I were horsing around on our twin beds, struggling over the small lead replica of the Empire State Building our father had brought back from the East. Ernest aimed it at me as if it were a gun—“Bang! Bang! Pow!”—and on my back I deflected the bullets, kicking up at him fearlessly. Our anarchy was the better for knowing we’d have to put on Sunday School penitentials before long. The door opened and in walked our mother and Grandma Lockridge, which stopped our play. They were sleepy-eyed. Ernest, aged nine, knew something was wrong. Our mother placed her hand gently on his shoulder and said, “Honey, your father is dead. He died last night.”

Ernest screamed and fell sobbing on the floor and I, aged five, was puzzled and a little embarrassed, for Mom and Grandma didn’t make it sound so bad. Our father had been tired, he needed a rest, he was now in a warm and sunny land, but no, he wouldn’t be coming home soon.

I tried to see my father in a space above my own, walking carefree amid trees and flowers, and hoped he’d soon be rested up.

Later that morning Ernest still lay on the floor. He’d stopped crying but hoped his mother would come in and find him lying there—then she would know how much he had loved his father and how dead with grief he was. But she was busy with funeral preparations, and he was tired of lying on the cold floorboards and got up and dressed.

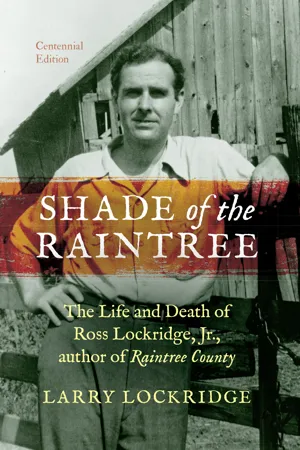

The death of fathers is a common theme, but the suicide on Saturday evening, March 6, 1948, of Ross Lockridge, Jr., author of the novel Raintree County, was improbable enough to be the subject of many editorials. At his death his novel was first on the New York Herald Tribune’s best-seller list, had won the enormous MGM Novel Award, had been excerpted in Life, and had recently been the Main Selection of Book-of-the-Month Club. He left a wife and four children.

“The death, apparently by suicide, of Ross Lockridge, Jr., author of Raintree County, has stirred a wave of shocked speculation among his countrymen,” noted the Washington Evening Star. “What more, they wonder, could a man ask of life than had been granted this 33-year-old writer, whose first book, an unabashed attempt at the great American novel, brought him wealth and fame and recognition. . . . Curiously enough, one of the book’s most notable aspects was its staunch repudiation, through its hero, of materialism, its repeated affirmation of faith in the American dream and the American destiny. How did the author lose the hope and optimism expressed by the hero who was presumably his spokesman? . . . We shall never know, since evidently the only testament he left is his questing, vital, sprawling book. He seems to have gained the whole world and then to have wondered what it profited a man. We can only pity the desolation and confusion of his going.”

My book is a quest, four decades later, to overcome confusion and lay bare this desolate act—and, more so, the life and work that preceded it. Pablo Neruda wrote that, in death, Ross Lockridge had joined Melville, Whitman, Poe, Dreiser, and Wolfe as American writers who were like “fresh wounds of our own absence.” They were all “bound to the depths” and “to the darkness,” were “checked in their work by joy and by mourning”—and yet over them “the same dawn of the hemisphere burns.” I’ll tell the story of my father’s life, from dawn to darkness, for the intensities of will and creative intellect we might find there. A full measure of them has not yet been taken. His was an American life of great aspiration, a life of prodigious labors ending in a sense of dead enormous failure even before the applause began. Few driven spirits give way to darkness so irrevocably, but I believe that in some ways Ross Lockridge’s life is an allegory of the American writer.

I always took pride in the The New York Times giving him a front-page obit. The circumstances of the death were chronicled there. “Dr. Robert E. Lyons, Jr., Monroe County Coroner, who returned the suicide verdict, said he had not been able to determine a motive. Mr. Lockridge was found unconscious in his car in the gas-filled garage of the new home he built with part of a $150,000 movie studio award for the book. He wrote the novel in seven lean years of trying to break into the writing field. Dr. Lyons said that relatives told him Mr. Lockridge appeared to be in good spirits yesterday. . . . Mr. Lockridge left no letters or notes indicating he was despondent or ill. . . . Mrs. Lockridge became alarmed last night when her husband failed to return after a reasonable time from a trip to the post office. She went to the garage shortly before midnight to see if the car was back and found the doors locked and the garage lights on. The car was inside. She summoned neighbors, who smashed in the doors. They found the car’s motor running and Mr. Lockridge sprawled in the driver’s seat. The door was open and his legs were hanging over the running board. The garage was filled with carbon monoxide fumes.”

This account permitted many of his friends to think it an accident. Maybe he was listening to the regional high school basketball tournament over the car radio and passed out, maybe he hit his head when exiting. Here was an exuberant writer known for thoroughness in all matters who hadn’t left a note, who hadn’t made out a will, who in a letter to his lawyer on the day he died alluded to future books. But our mother, years later, didn’t encourage us to think it an accident. And I’d come to dislike the idea that it could have been. However bleak, suicide is a willed act invested with human meaning.

But if it was suicide, it seemed less premeditated than impulsive. Those legs exiting the Kaiser’s front door even hinted at a lastminute change of mind. Somehow I wanted my father to have done what he fully intended to do.

Grandma Lockridge, a Christian Scientist with a master’s in psychology, felt the four Lockridge children shouldn’t attend the funeral, and our mother gave in on this, as she would later rue. But we were there for the wake. My younger sister, Jeanne, had, like the rest of us, been dispatched to relatives while funeral arrangements were being made. Aunt Lillian—an obese woman once photographed standing next to Revolutionary War cannons by my father, who wrote the caption “They shall not pass!”—was in charge of Jeanne. Barely four years old, she had little conception of what was happening.

She could see, arriving at our house, that the living room was full of flowers and she knew it had something to do with her daddy. “I want my daddy! I want my daddy!” she screamed as she fought to get free of Aunt Lillian. She ran to the coffin, was picked up by someone, and stared at the white skin, puzzled that her father was in a box and seemed to be sleeping. She satisfied herself that he was breathing. She and I then ran through the crowded living room, endangering floral displays with hide-and-seek around the coffin—she trying to wake him up—taking it all for a party until somebody subdued us. Jeanne would later be surprised that her breathing, sleeping father was simply gone.

Ernest returned from our uncle’s home in Indianapolis. Furtively he reached into the coffin and touched his father, who felt like ice. On a piece of paper he wrote “Daddy I love you” and stuck it in the coffin. He could never again stand the smell of flowers, the taste of pineapple pie. Earlier, next to the typewriter in his father’s bedroom, he had found a typed page entitled “Ultimate Philosophy” and scribbled guns all over it.

Not attending the funeral would have consequences for Ernest—it would complicate the work of mourning. Jeanne and I would gradually learn of death’s finality. Terry Ross, two years old, would learn to mourn a father he could hardly remember. At the wake his mother held him above the coffin so he would see his father lying there. Later that day he saw his father’s pajamas in the downstairs bedroom. “Daddy?” he asked.

Confident that we would learn in our own time and way what we needed to know, our mother set no agenda for discussing the dead father, but would narrate luminous moments of their life together. We children didn’t much discuss him or ask many questions of our mother, though she answered what little we asked. Rather we began private dialogues with him that continued over the years. We had been thrown into a story so rich in vital promise that to allude to our father and his novel was to mourn a bright universe lost. We couldn’t speak casually about this founding catastrophe.

The house at 817 South Stull Avenue, Bloomington, Indiana, contained a number of relics that prompted these dialogues. His dress shoes were in our mother’s closet, his shaving mug and eyewash cup in the bathroom medicine chest. We’d take our family picnics on his cream-and-crimson varsity blanket. On the walls there hung a drawing of the novel’s hero, John Shawnessy, struggling to pull himself by a root out of the Great Swamp, a silkscreen of Senator Garwood B. Jones arriving at Waycross Station, and a painting of the book jacket after my father’s design. Only when I reached puberty did I see that the green map of the county disclosed in its contours a woman’s naked body.

I learned to play the piano with two pictures of him, one serious and one smiling, staring at me from atop the Acrosonic. And at the foot of the wooden staircase was a large publicity photograph—a handsome man seeming to smile with the self-assurance of a movie star, with FDR’s posthumous Nothing to Fear cradled on his lap. When we went upstairs to our rooms for serious tasks or sleep, his eyes followed us as if in ghostly encouragement.

From time to time our mother would take us through the many photo albums of their marriage, including one of great poignancy he made shortly after his novel was accepted. The visionary landscape of Raintree County, sketched in pencil, merges with photographs of familiar Indiana pastoral scenes, and Ross and Vernice are smiling together in photos going back to their courtship days. “ ’Tis summer and the days are long!” As my sister would write, his memory “has been carefully preserved for us by our mother and others, like a rare and beautiful life-form, long since extinct, preserved in translucent amber.”

Once a year, on Memorial Day, we’d visit his grave at Rose Hill Cemetery in Bloomington, taking peonies, pulling weeds, and cleaning spider eggs out from his name on the simple granite marker. We’d watch the parade and the DAR ladies reading poetry—“Ain’t God good to Indiana? Ain’t he, fellers, ain’t he though?”—and adjourn to the radio broadcast of the Indy 500, which compounded our domestic tragedy with fresh deaths of its own.

Jeanne and I didn’t find out our father was a suicide until she was ten, I eleven. A neighbor girl taunted her after school one day—“Your daddy killed himself! Your daddy killed himself!” My mother brought me into the room with Jeanne to say yes, the neighbor girl was right and it was time for us to know. He’d had a nervous breakdown and felt he would never be well again. Jeanne cried, but once again I silently wondered what this meant.

It still seems remarkable to me that there could have been so uniform a silence among Bloomington children and adults. I hadn’t learned for six years what most townsfolk already knew and what Ernest knew instinctively from the beginning. We all know that silences are as compelling as words spoken—and suicide, insanity, sex, and unorthodoxy are matters that families and larger communities often decline to make more real through talk. I suppose the silence in Bloomington came out of cautious respect for family privacy. Amid genuine sympathies, people often presume that suicide survivors must feel some shame, and what good comes anyway from reminding others of their tragedies?

The most sacred relic around the house was the novel itself, which was anything but silent about sex and unorthodoxy. Raintree County had been prominently denounced as obscene and blasphemous, and to this day some Indiana folk think he “got what he deserved for writing that dirty book.” A small portion of the original manuscript, which he wrapped up with a belt while burning the rest, was left untouched on top of Ernest’s and my bookcase. The novel has gold antique lettering on a green cover, and a book jacket blurb that ends, “Through all vicissitudes of residence and travel, the Lockridges have considered Bloomington their home town.” Shortly before he died he signed copies for each of us—with his signature only, no personal message.

Even so, the novel spoke to us like a testament from the grave and resuscitated its author in every reading. He left no instructions as to how we should carry on, and I recall my puzzlement as to how I was to fill in this fatherless future. But he left a novel that some critics would read as the incarnation of an enormous vitality, with all sorts of implicit imperatives. Others would read it as an unusually gaseous suicide note.

Thus we grew up with a novel instead of a father—a novel attempting “no less than a complete embodiment of the American Myth,” not just a chunk of it. So driven by the quest for ultimate meaning, so warmed by eroticism, so full of its own search for origins and fatherhood—ending with “a signature of father and preserver, of some young hero and endlessly courageous dreamer”—and so suffused with a sense of loss, Raintree County was to us a haunting. It was an extended letter left to us, with a hero who seemed like our father—exuberant, ambitious, maybe all too good—except that Shawnessy survives in the end.

In 1979 a critic said of Raintree County that it was “an ecological novel written before its time, and its time has finally come.” He noted its impassioned evocation of this biological planet and its lament at industrial rape. In the Great Swamp, John Shawnessy sees the astonishing beauty of plants and insects as he searches for an Asian tree said to have been planted by Johnny Appleseed.

Though I never warmed to bugs, I felt a similar biological imperative and a sense of the land’s pagan antiquity whenever the southern Indiana spring arrived. A few times as a young adolescent I set out on solitary journeys through river goo and poison ivy, reenacting the feverish pastoralism of the novel.

It is written like a decipherment, with parchment maps and an old county atlas and aboriginal swamp sounds that hint of generous meaning. These beckon its hero to return to origins in a landscape that wears a human face and has imprinted in the contours of its river his own initials. I suppose my adolescent reenactment was an attempt to find the signature of my father in the Indiana wilderness, and perhaps his blessing, but I knew at the time that this was too literal-minded a search for symbols.

I’d feel a rebuff whenever we drove through Henry County, Indiana—the prototype of the novel’s county and ancestral home of my father’s mother. Signs on the old National Road still inform confused drivers that they are entering “Raintree County.” You will look hard and wide for the Shawmucky River, Paradise Lake, and the Great Swamp, and they won’t be there in this unarresting farmland some twenty-five miles east of Indianapolis.

You find human testimonials, though: “Raintree Auto Sales,” “Raintree Bait and Tackle,” “Raintree County Dairy,” “Raintree Barber and Styling Shop,” “Raintree Industries,” and “Raintree Muffler Shop.” My father enhanced Henry County with the Eel River, lifted from Miami County where his father had grown up, and with the raintree itself, lifted from the utopian community of New Harm...