![]() PART ONE

PART ONE![]()

CHAPTER ONE

In the Beginning: Before There Were Sunnis and Shi‘is

The split in Islam between Sunnis and Shi‘is is often traced back to the question of who should have led the Muslim community after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 AD. Failure to resolve that question to the satisfaction of all resulted in a great scandal: a civil war among Muslims over the leadership of the community. This began less than twenty-five years after the Prophet had been placed in his grave, and while there were still many people alive who had known him well and loved him.

One side to that civil war is often presented today as consisting of those who said that Muslims should choose the best available leader for their community. There were only two provisos. The first was that he should be a leading figure who was known for his devotion to the faith. This meant that he should be chosen from among the Prophet’s eminent Companions while they still lived. The other was that he must be from the tribe of the Quraysh to which Muhammad had belonged. This requirement may seem rather unnecessary to a modern reader who is unfamiliar with the history of Islam, but there were sound reasons for it at the time, as we shall see. The opposing party, it is frequently said, was made up of those who argued that leadership could be provided only by someone who was in the bloodline of the Prophet: initially, his cousin Ali, who was his closest living male relative at the time of his death and was married to his daughter Fatima. According to this view, the community should thenceforth always be led by a male descendant of that union.

Looked at this way, the dispute appears as much political as religious. It can even be interpreted as the pitting of those who favoured a somewhat more democratic form of religious authority (the Sunnis) against those who supported a strictly monarchical one (the Shi‘is). As time passed, the split would appear to take the form, at least on the surface, of struggles between rival dynasties. Yet there has not been a caliph with a strong claim to universal acceptance among Sunni Muslims since 1258, the year in which Hulegu the Mongol sacked Baghdad. According to the most widely known account, he ordered the last of the Abbasid caliphs to be wrapped in a carpet and trampled to death by a soldier on horseback. This form of execution was chosen because Mongol protocol dictated that royal blood should not be seen to be spilled. As for the Shi‘is, apart from a few groups such as the Ismaili followers of the Aga Khan who are a small minority even among them, none today pledge their allegiance to a worldwide religious community in which the supreme authority is a living descendant of Ali and Fatima.

Yet today the division between Sunnis and Shi‘is seems very much alive. It is frequently seen as an important aspect of the conflicts that have been ravaging Syria and Iraq over the past few years, and of the power politics playing out between Saudi Arabia and Iran. There must therefore be something more behind it than ancient civil wars and half-forgotten dynasties. We have to follow the history from the beginning right through to the present if we wish to understand the division and its impact on us now. Over time, incompatible narratives to explain the history of the early Muslim community emerged. These would split Islam. In Islam, as perhaps in other religions, history and theology became permanently intertwined.

I

Islam’s central tenet is faith in the one true God. It shares this with Christianity and Judaism, alongside belief in the Last Judgement, the Resurrection of the Body, Heaven and Hell. Even though the three religions have important differences which divide them, each enjoins its followers to live their lives in accordance with core virtues that are shared by them all, such as compassion, honesty, generosity and justice. Islam’s sacred scripture, the Qur’an (literally ‘the recitation’), consists of passages which Muhammad believed were revealed to him by the angel Gabriel. From the earliest days of the faith, the revelations that make up the Qur’an were known to be distinct from everything else the Prophet said. The Qur’an is not the sole source of Muslim teaching, however, since all Muslims agree it is to be amplified by following the example of the Prophet and emulating the way he lived his life.

The hallmarks of Islam are to be found in Muslim devotional practices – such as the formal prayers that are to be said at prescribed times over the course of the day, the fasting during the holy month of Ramadan, and the pilgrimage to Mecca known as the Hajj. But the religious laws that govern the way Muslims should lead their lives are also key to living the religion. These, too, are based primarily on the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the customs established by the Prophet. After his death, the community was faced with many important questions. Among the most important was how to formulate and interpret these rules that govern the way Muslims perform their devotions and lead their lives. They make up what came to be known as the Sharia (literally, the path to the watering hole in the desert).

The Prophet had died fairly suddenly, and had not made any clear arrangements accepted by the whole community as to who was to lead it after his death. He had not instituted any kind of priesthood or left behind an uncontested teaching authority on spiritual matters. Moreover, ever since the Prophet’s Hijrah, or emigration, from Mecca to the oasis of Medina some ten years before he died, the Muslim community had been a political entity. It had since grown into what today we would call a sovereign state, and required political leadership. This had been ably supplied by the Prophet himself while he was alive. Who was best qualified to supply it now? There were pressing problems of statecraft that had to be addressed at once. These were likely to involve murky compromises and messy decisions by a leader who would also be required to have the purity of heart needed to give guidance on spiritual matters. Sooner rather than later, this was likely to lead to a hard choice for the community: the person best able to exercise authority over it as an effective political leader might not be the most suitable candidate to be its spiritual guide.

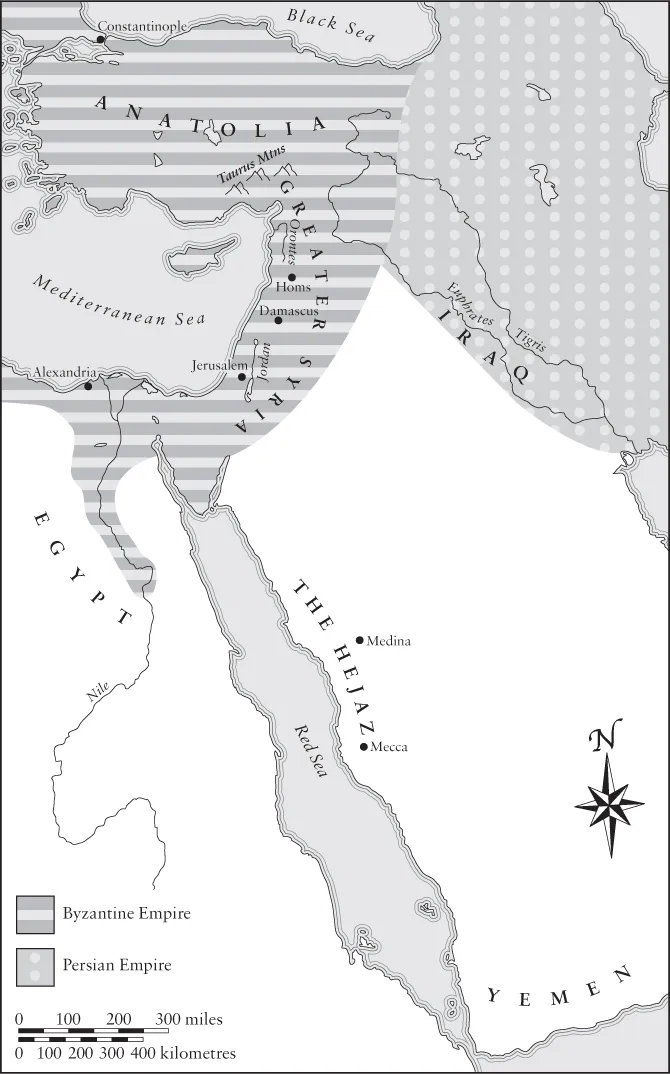

By the time Muhammad died, the community he had founded had come to dominate the desert subcontinent of Arabia. He had made Medina his capital, but Mecca, not Medina, was his native city and the place where he had begun his mission. Apart from the relatively small band that had responded to his initial preaching, the Meccans had been indifferent to his message or had actively opposed it. After a while, the city’s fathers had made the situation of the first Muslims very uncomfortable. The result had been that Muhammad had gone to Medina, a large oasis with considerable settled agriculture that lay more than 250 miles to the north, where he already had some followers. This was in response to an invitation to act as a kind of resident arbitrator in disputes between the tribes living there – a position that would imply a degree of leadership. He had charisma and wisdom, and was known for his trustworthiness. He would have appeared an ideal outsider to fulfil such a role.

To the Muslim Muhajirun or ‘emigrants’, who set out for Medina from Mecca in unobtrusively small groups, there were now added Medinan converts who became known as the Ansar or ‘helpers’. They were able to consider the Prophet one of their own, since his paternal grandmother had originally come from Medina. Yet not all the inhabitants of Medina converted. The Jewish tribes in the oasis retained their own religion, and substantial numbers of the other inhabitants remained polytheists. Despite this, over time Muhammad became the most powerful man in the oasis and its de facto leader. That leadership eventually consolidated into rule. Initially, however, his authority was on sufferance, except as far as his Muslim followers were concerned. His position of pre-eminence stemmed from agreement, especially treaties of alliance with the major tribes. While he was still in Mecca, conversion to Islam had involved the risks of ostracism, discrimination and active persecution. We can therefore assume that all conversions while he had been in Mecca had been sincere. But now, in Medina, it became expedient for many to accept Islam for reasons of self-interest. This large group was referred to as the Munafiqun, generally called ‘the hypocrites’ in English, who are frequently attacked in the Qur’an.

War with Mecca broke out almost immediately after Muhammad went to Medina, and seems to have been initiated by him and his followers. In contrast to the agricultural lands of Medina, Mecca was situated in a dry, rocky valley and had little or no agriculture of its own. Its prosperity depended on trade and, to a lesser extent, on its status as a pilgrimage destination, since it possessed the shrine of the Ka‘ba, which tradition stated had originally been built by Abraham and his son Ishmael (Ibrahim and Ismail in Arabic), although it was now a crowded house of idols. Meccan caravans had to pass Medina on their way to and from Syria, and it was this trade that Muhammad and his followers began to raid as a source of booty. By attacking its trade with Syria, he was threatening Mecca’s lifeblood.

ARABIA IN THE TIME OF THE PROPHET

Raiding of this sort was permitted by long-established Arabian custom. The tribe was the basic social and political unit of pre-Islamic Arab society, and rights and obligations were limited to those towards other members of the tribe, and the upholding of whatever agreements the tribe may have entered into with others. Third-party arrangements included relations with other tribes, as well as engagements with individuals or groups who might seek the tribe’s protection. The deterrent of vengeance, the old cry of an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, was the cornerstone of justice and the only way in which law and order were maintained. It could be exacted not merely against the perpetrator of a wrong, but against any member of the wrongdoer’s tribe. Not for nothing was ‘persistence in the pursuit of vengeance’ a cornerstone of the central Arab virtue of hilm, the quality which also combined steadfastness, courtesy, generosity, tact and self-control, and was the characteristic most sought after in the leader of a tribe.

This illustrates just how hard and lawless life was in seventh-century Arabia. It was not just the barrenness of the desert that was harsh. It had produced a brutal society that practised, among other extreme acts, the infanticide of unwanted baby girls. Not only was the physical environment hostile, but the lack of any settled government meant that there was no social unit above the tribe. Islam was something entirely new. When somebody became a Muslim, this meant that he or she had a new allegiance and a new code of conduct that overrode that of the old tribal customs. Tribal relationships were modified among those who had accepted the new religion, and the brutality of those relations softened by the teachings of Islam. If one tribe had a claim against another for the murder of one of its members, the Qur’an taught that the life of the murderer was forfeit – but it would be better and more praiseworthy to renounce the right to the murderer’s death and accept blood money instead. Islam forbade the killing of another member of the murderer’s tribe on the old basis of an eye for an eye, so vengeance could now be exacted only against the murderer himself. The death penalty for the murderer or acceptance of compensation was the choice for the victim’s family, and the victim’s family alone, to decide.

Islam provided a kind of ‘super-tribe’, of which all Muslims were members. Yet Islam did not replace tribalism as such. That would have been impossible in seventh-century Arabia, and there is no sign that the idea even occurred to the Prophet. The converts to the new faith formed a community that closed ranks against outsiders, such as the polytheists of Mecca, but the community’s relations with the tribes of Mecca (and elsewhere) were still based on the old tribal customs. The Muslim attacks on Meccan caravans would have been understood in these terms by everybody in Arabia. Tribes which had converted to Islam would now focus their energies on spreading Islam, rather than dissipating it on raids against each other and blood feuds.1

II

During the ten years between Muhammad’s Hijrah from Mecca to Medina and his death, he gradually rose to be the undisputed leader of much of Arabia. This was an extraordinary feat of political skill. First he had to make himself the leader of the whole oasis, then overcome the opposition of the Quraysh tribe which ruled Mecca, and finally spread his message far and wide across a desert subcontinent.

The first major military encounter between the Muslims and the Quraysh was at the wells of Badr, when a smaller force of Muslims defeated a Meccan army sent to escort a trading caravan returning from Syria. Muhammad received a revelation that divine help, in the form of legions of angels, had aided the Muslims. The victory simultaneously boosted Muslim morale, lifted their prestige among the non-Muslim inhabitants of Medina, and turned the struggle with Mecca into open warfare. For the sake of the tribe’s own standing, the Quraysh needed to take revenge.

This is what they sought a year later. A large Meccan force approached Medina. Muhammad met them at Uhud, a mountain outside the oasis. Initially, it looked as though the Muslims were gaining the upper hand. Excited rumours spread through the Muslim ranks that the Meccan camp was about to fall, and soldiers rushed forward in the hope of booty. The result was that archers guarding a flank abandoned their posts, and the Meccan cavalry were able to wheel round and attack the Muslims from the rear. Most of the Muslims were able to escape to high ground and lava-flows where they were safe from the enemy cavalry, but the Meccans were left in possession of the main battlefield. Muslim casualties were heavy. The Prophet himself was wounded. One of the men closest to him, his uncle Hamza, was killed. Hamza’s body was mutilated and Hind, the wife of the Meccan leader Abu Sufyan, ritually chewed part of his liver in revenge for the death of her father, son, brother and uncle who had all been killed at Badr.

The defeat also demonstrated that Muhammad’s leadership was still fragile. A large party of Munafiqun under Abdullah bin Ubayy, a tribal leader in Medina who aspired to rule the oasis and resented the prominent position Muhammad had acquired, deserted him before the battle. At the same time, the Jewish tribes and some others had remained neutral. Muhammad had clearly not consolidated his control of Medina at this point, yet he was able to ensure that Uhud was no more than a setback. The defeat made it necessary for him to redouble his efforts to extend his authority.

The Jewish tribes in the oasis presented him with a problem. They rejected his status as a messenger of God and argued that the truth lay in their own scriptures, not the Qur’an. On the ideological level, this made them his most dangerous opponents. One of the Jewish tribes, the silversmiths of Banu Qaynuqa‘, had already been exiled after the Battle of Badr. Now, Muhammad moved against the wealthiest Jewish tribe in the oasis, the Banu Nadir. Following allegations of their treachery, he laid siege to their village. It was eventually agreed that they would surrender their arms and leave the oasis with their moveable property. The siege of the Banu Nadir had demonstrated the weakness of Abdullah bin Ubayy’s position, since he was bound to extend his protection to them. However, it had now been shown that he was not strong enough to challenge Muhammad. The departure of the Jewish tribe was therefore a humiliation for him and another major step towards Muhammad consolidating his authority in Medina.

The Quraysh now sought to destroy Muhammad once and for all. A much larger army than the force that had fought at Uhud was assembled and joined by major confederations of tribes. This time, rather than march out of the oasis to...