![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Fettered Development

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production ... From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution.

Karl Marx, Preface to A Contribution to the

Critique of Political Economy, 1859

When a revolutionary upheaval is not an isolated phenomenon attributable to specific political conditions in a particular country, but constitutes a shock wave that goes beyond the merely episodic to initiate a veritable sociopolitical transformation in a whole group of countries with similar socioeconomic structures, Marx’s thesis cited above takes on its full significance. From this perspective, the “bourgeois” revolutions at the heart of the Age of Revolution – from the sixteenth-century Dutch War of Independence and the seventeenth-century English Revolution through the long process comprising the French Revolution to the 1848 European Revolutions sometimes called the Spring of Nations – appear as a series of earthquakes triggered by the collision of the two tectonic plates Marx identified as developing productive forces and existing relations of production. The latter are represented by what the author of Das Kapital calls the “legal and political superstructure”, with the state at its core. These revolutions accelerated the transformation of the predominantly agrarian societies of the late feudal period into societies dominated by the urban bourgeoisie. They thus paved the way for capitalist industrialisation.

A comparable instance of the existing relations of production blocking the development of the forces of production was at the origin of the shock wave that, beginning with Poland in 1980, overturned all the Central and Eastern European “communist” regimes and culminated in the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union (USSR). This shock wave put an end to the bureaucratic mode of production of the USSR and Eastern Europe, undermined by stagnation at its very centre, and put a “market economy” in its place. With that, the process of capitalist globalisation was essentially completed. It has not been sufficiently stressed just how striking an illustration of Marx’s thesis this historic turn provides – a new irony of history, since the overturned regimes claimed to take their inspiration from his “doctrine”. Yet it was a Marxist critic of the Soviet regime, Leon Trotsky, who was the first to predict – in 1936, at a time when the “socialist fatherland” was posting record growth rates – that the bureaucratic command economy would ultimately founder on the “problem of quality”.1 Trotsky thus anticipated the period beginning in the early 1970s, later named the Era of Stagnation, which culminated in the collapse of the regimes descended from Stalinism.

Is what we have been witnessing in the Arab region since 2011 an “era of social revolution” brought on by a blockage impeding the development of productive forces? If so, is this blockage due to factors common to the countries of the region and specific to them, as in the two historical cases just mentioned? The question is worth asking, if only because the tremor running through the region has affected the whole of it, from Mauritania and Morocco to the Arab-Iranian Gulf. That, moreover, is why observers have compared the upheaval underway in the Arab countries with the shock wave that traversed Eastern Europe in the 1980s. Yet this upheaval has not – at any rate, not yet – brought about a radical change in the mode of production. There seems to be no change on the horizon of the revolutionary process unfolding today in the Arabic-speaking region profound enough to invite comparison with the great upheaval that ultimately integrated the “communist” countries into globalised capitalism.

Whereas the European upheaval of the 1980s resulted from a crisis at the very heart of the bureaucratic mode of production, the crisis in the Arab region affects only one of the peripheral zones of today’s globalised capitalist mode of production. Hence it cannot, by itself, be regarded as a manifestation of a general blockage of this mode of production, nor even – since capitalism continues to generate development in other peripheral zones – a blockage confined to the capitalist periphery. Indeed, even if the crisis currently besetting the highly developed economies central to the world system (the European economies, above all) eventually proves to be the expression of an insurmountable blockage leading to sociopolitical upheaval, the coincidence of this crisis with that rocking the Arabic-speaking region can hardly be interpreted in terms of cause and effect.

The fact that the crisis in Arab countries is clearly limited to them as far as its peculiar modalities are concerned plainly shows that specific factors are at work. It is neither a symptom of the general crisis of globalised capitalism, nor even a symptom of the crisis of “neoliberalism”, the dominant management mode in the current phase of capitalist globalisation. To identify the specific factors at work, we must compare the Arabic-speaking region with others on the periphery of the world economic system – particularly the countries of the Afro-Asian group of which the Arab region is a part.

Nevertheless, Marx’s paradigmatic thesis on revolution should not be ignored when explaining the ongoing upheaval in the Arab world. Simply, we have to derive variants that are less sweeping in historical scope: the development of productive forces can be stalled, not by the relations of production constitutive of a generic mode of production (such as the relation between capital and wage-labour in the capitalist mode of production), but, rather, by a specific modality of that generic mode of production. In such cases, it is not always necessary to replace the basic mode of production in order to overcome the blockage. A change in modality or “mode of regulation” does, however, have to occur.

Such changes do not necessarily presuppose social or even political revolutions. They can result from economic crises that induce the economically dominant class to change tack. Capital has negotiated more than one such turn in the course of its history. Both the 1930s Great Depression, followed by World War II, and the generalised recession of the 1970s precipitated sharp changes of tack, leading in two diametrically opposed directions. Certainly, the social balance of forces entered into the equation in both cases: the workers’ movement was strengthened by the first crisis, weakened by the second. But these were not periods of social revolution or counter-revolution in the proper sense.

These changes in the management mode occurring within a basic continuity of capitalist relations of production illustrate, in some sense, another of Marx’s theses. He presents it shortly after the passage in the 1859 Preface that serves as the epigraph to this chapter:

No social formation is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed, and new superior relations of production never replace older ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework of the old society.2

Yet there also exist situations in which the development of productive forces is held back, not by a “simple” crisis in regulation or management mode, but by a particular type of social domination, one sustaining a specific variant of the generic mode of production. In such cases, the blockage can be overcome only if the dominant social group is overthrown, that is, only by a social revolution. Yet that revolution will not necessarily precipitate a radical change in the mode of production. We may here make use of Albert Soboul’s definition of “revolution” as a “radical transformation of social relations and political structures on the basis of a renewed mode of production”,3 as long as we admit that such renewal may be limited to a profound change in the modalities of a mode of production, with no accompanying change in the generic mode itself.

For capitalist development can be blocked by a distinct configuration of dominant social groups sustaining one particular modality of capitalism, rather than by the general relations of production between wage labourers and capitalists and the attendant property relations (private ownership of the social means of production). Later we will discuss the conditions under which such a blockage can be overcome, as well as the social dynamics that may accompany that process. What matters for present purposes is the blockage itself. We must therefore first determine whether, in the case at hand, such a blockage exists.

The Facts

The most frequently cited indicator of economic development – in the sense of growth, considered without regard to other aspects of human development – is an increase in gross domestic product (GDP), both in absolute terms and also relative to the size of the population. This indicator is, of course, very much open to discussion (a point to which we will return), but it does provide some idea of the relative development of the production of goods and services: its growth over time as well as variations in the pace of development in the various countries and regions of the world.

It so happens that, of all the regions still referred to as the Third World, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is the one facing the most severe developmental crisis. After the 1960s, when most of this region’s economies were dominated by the public sector in line with a state-led developmentalist perspective, the 1970s saw the inauguration and gradual extension of policies of infitah (opening), the name then given to economic liberalisation in the Arabic-speaking region. Infitah went hand-in-hand with public sector privatisation and an erosion of social gains. Certain MENA countries, notably Egypt, thus prefigured the “structural adjustment programmes” that would be imposed on the whole planet from the 1980s onwards in the framework of neoliberal deregulation.4

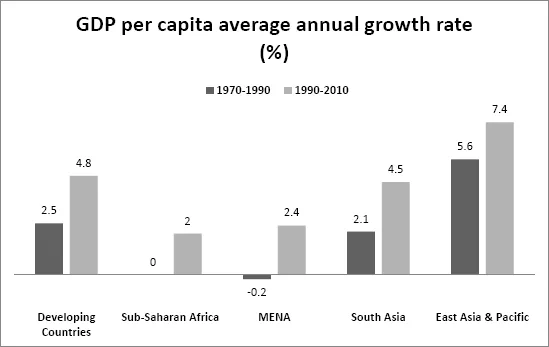

The available data plainly show that the two decades between 1970 and 1990 saw stagnation in per capita GDP in MENA: the GDP’s per capita average annual growth rate (at constant prices in local currencies) was even slightly less than nil. Although that growth rate became positive again in the two following decades, it remained at levels well below – 50% below – the average rate of increase in developing countries (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 (Source: UNICEF)

It goes without saying that the regional average masks disparities between individual cases. But the fact remains that most of the positive performances in the 1970–90 period were inferior, or at best equal, to the average performance in developing countries. Egypt was set apart from the other countries in the region with an average annual rate of 4.1% in 1970–90; this growth rate, substantially higher than that posted by the other MENA coun...