![]()

1

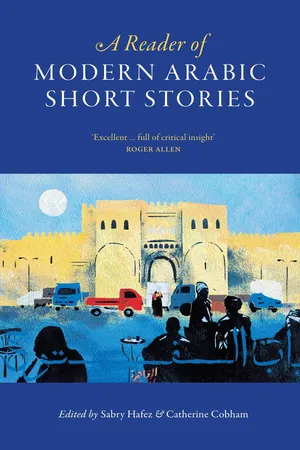

Shams Saghīra

Zakariyya Tāmir

1. Zakariyya Tāmir

Zakariyya Tāmir was born in 1929 in Damascus. After he had finished compulsory primary education he was apprenticed to a blacksmith, but later became interested in politics and was encouraged by contact with intellectuals to continue his education at night school. He read voraciously and was provoked by his reading, as he later said in an interview, ‘to create a voice which [he] hadn’t been able to find [there]’ (Al-Maʿrifa, August 1972). His intention was to represent in his writing the very poor majority of men and women in Syria, with their joyless and restricted existence; these were for him the materially and spiritually deprived members of the society rather than the more picturesque characters like beggars and sellers of lottery tickets whom he accuses the ‘soi-disant committed writers’ of concentrating on almost exclusively. His claims to have taken a new direction were certainly borne out by the great influence he was to have on short-story writing, especially in Syria, Iraq and Egypt. On the other hand he began writing in a literary climate influenced by predecessors and near-contemporaries such as ʿAbd Al-Salām Al-ʿUjaylī, Saʿīd Hūrāniyya and Mutāʿ Ṣafadī in Syria and the Egyptian writers of the late 1940s and early 1950s, including Yahyā Haqqī, particularly in his two collections Qindīl Umm Hāshim (1944) and Dimā’ Wa Ṭīn (1955). Tāmir published his first collection of short stories in 1960 and since then has published seven other collections and many individual stories. He also writes children’s stories and works as a freelance journalist. He left Syria in the early 1980s and has lived in the UK ever since.

When he became a writer and journalist he joined a different social milieu from the one he had been born into but he tended to view the sufferings of his fellow intellectuals from the outside, retaining the memories and perceptions of poverty and deprivation from his own early life. In many of his stories he emulates or parodies popular folk-tales and plays with time, place and subject matter in a ‘magical’ way, juxtaposing things which are not normally found together and breaking down the barriers between dreams and reality. The syntax and vocabulary of his stories are simple and the complexity and ambiguity in them are not to be found in the thought processes or actions of his characters but in their dreams and fantasies. These dreams, or illusions, or substitutes for thought, help people to bear their lives but are also perhaps indicative of a lust for a more beautiful life and a desire for change, as well as being sources of deadly frustration.

The act of killing also figures in nearly all of Tāmir’s stories. It is often described in sensuous detail and presented as a positive act, a removing of obstacles. It is a shock tactic at the same time, used to awaken the reader to the continuous clash between human beings and oppressive authorities, and as such is relevant to the everyday realities of life in Syria rather than to a general metaphysical view of the human situation. Tāmir views the particular situation of his characters as nightmarish and oppressive, and his simple images of power and beauty, often referring to animals, the countryside or natural phenomena, make moments of brightness that eventually only emphasize the extent to which darkness and injustice have penetrated, leaving nothing in the society untouched.

2. Shams Saghīra

Abū Fahd, the hero of ‘Shams Saghīra’ (1963), is a Chaplinesque figure as he walks down the narrow alleys of a poor quarter of Damascus after three glasses of arak, singing to himself. He begins to find his harsh voice beautiful and he has a momentary picture of a rapturous reception from a large audience, but before his dream becomes sentimental he laughs at himself and continues on his way singing with even greater delight.

His encounter with the sheep is described in matter-of-fact, humorous terms. It is strange to find a sheep wandering without an owner and, magically , it speaks and promises him gold, but the narrative is mainly concerned with Abū Fahd who tries to drive it along or pull it by its little horns, and finally carries it on his back, because initially it represents to him a huge supply of free meat.

The mixture of tenderness and irritation shown by Abū Fahd’s wife when he returns home is portrayed delicately in few words; for example, when he is tired and dispirited she abandons her scepticism and supplies him with information about the habits of the jinn, and then, when he sets out again she is timorous but instinctively helps him gird himself for battle, winding the sash around his waist. This has the effect of refining the popular-comic nature of the scene of the couple in bed discussing what they will buy and how they will change their lives and that of their unborn child when they are rich. There is a hint that their child may have a life as circumscribed as theirs, as they plan his future career for him, but this sardonic note does not seem to indicate cynicism towards the characters, rather some bitterness and anger from the author that they humiliate themselves unconsciously in their daily lives.

The fantasy ends when a man, drunk as Abū Fahd was, or may have been, appears under the bridge and spoils the chances of the sheep returning; and yet humorously and ironically the drunk misconstrues Abū Fahd’s reasons for loitering under the bridge and quickly builds his own fantasy about a woman in whom he can have a share.

The violence which thwarts Abū Fahd and destroys him at the point where he believes he is measuring up to reality and is about to realize his dreams is described dispassionately as if the fight were a fairly matched contest or a strange dance. At the same time it turns out to be a harshly real event breaking in suddenly on a gentle tale. As Abū Fahd dies the dream returns too late and the gold he was promised falls on the ground in a heap, like a ‘little sun’ tumbling from the sky.

3. The Text

4. Textual Notes

![]()

2

Al-Khuṭūba

Bahā’ Ṭāhir

1. Bahā’ Ṭāhir

Bahā’ Ṭāhir was born in 1935 in Giza near Cairo where he went to school. His parents were originally from Karnak in Upper Egypt and he spent several long summer vacations there. He graduated in history from Cairo U...