![]()

Who was Derrida?

Jacques Derrida was a philosopher. Yet he never wrote anything straightforwardly philosophical.

His work has been heralded as the most significant in contemporary thinking. But it’s also been denounced as a corruption of all intellectual values.

Derrida has famously been associated with something called DECONSTRUCTION. Yet of all development in contemporary philosophy, deconstruction might be the most difficult to summarize…

What Is Deconstruction?

There have been many answers.

All of these (and more) have been said of deconstruction. But there’s some consensus on one point: its leading exponent has been Jacques Derrida.

Derrida’s writing undermines our usual ideas about texts, meanings, concepts and identities – not just in philosophy, but in other fields as well.

Reactions to this have ranged from reasoned criticism to sheer abuse – deconstruction has been controversial. Should it be reviled as a politically pernicious nihilism, celebrated as a philosophy of radical choice and difference… or what?

There’s much more to Derrida’s work than the public controversies suggest. But controversy can reveal something about what’s at stake in contemporary philosophy. A small quarrel at Cambridge has done precisely that…

BORDER LINES

According to a tradition dating from 1479, English universities award honorary degrees to distinguished people. It’s never been quite clear why. But it’s assumed that both parties benefit.

On 21 March 1992, senior members of the University of Cambridge gathered to decide its annual awards. It should have been a formality – no candidate had been opposed for twenty-nine years. But the name Jacques Derrida was on the list. Four of the dons ritually declared non placet (“not contented”). They were Dr Henry Erskine-Hill, Reader in Literary History; Ian Jack, Professor of English Literature; David Hugh Mellor, Professor of Philosophy; Raymond Ian Page, Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon. And they forced the University to arrange a ballot.

NON PLACET NON PLACET NON PLACET NON PLACET

There were two problems. First, this was a boundary dispute. Most of Derrida’s proposers were members of the English faculty, but by training and profession Derrida was a philosopher. But more trenchantly, Cambridge traditionalists in both disciplines saw Derrida’s thinking as deeply improper, offensive and subversive.

Campaigns were organized, and the Press was alerted. To the outraged dons, Derrida represented an insidious, fashionable strand of “French theory”. They struck Anglo-Saxon attitudes…

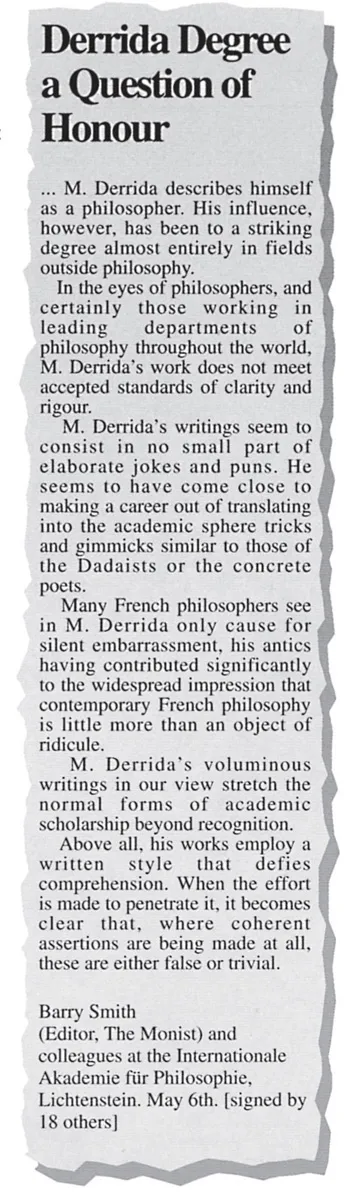

19 academics summed up the indictments in a letter to The Times:

Derrida is accused of obfuscation, trickery and charlatanism.

He’s not a philosopher, he’s a flim-flam artist. And strangely, his trivial joking gimmickry is seen as a powerful threat to philosophy – a corrosion in the very foundations of intellectual life.

But Derrida had his defenders, such as Jonathan Rée: “The traditionalists were offering a mere and meagre argument from authority. They were refusing the possibility of dissent from established systems – an establishment stance, yes, but scarcely a philosophical stance…”

The ballot on 16 May vindicated Derrida and his supporters by 336 votes to 204. Derrida collected his award. But the dispute has continued.

What was at stake? Underneath the posturing, there were two important questions:

If the dons had wanted a rigorous address to these questions, they might have found one in the writings of a certain Jacques Derrida…

The Critique of Philosophy

Derrida’s writing is a radical critique of philosophy. It questions the usual notions of truth and knowledge. It disrupts traditional ideas about procedure and presentation. And it questions the authority of philosophy.

So Derrida writes “philosophy” in something...