This is a test

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

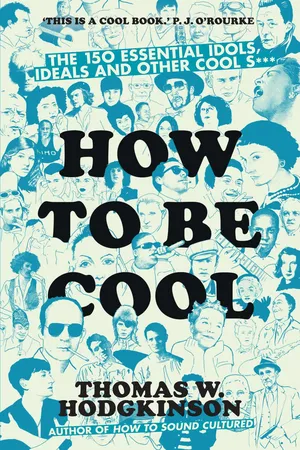

Cool can't be taught. That's the received wisdom, yet this wry, entertaining compendium by Thomas W. Hodgkinson (author of the indispensable How to Sound Cultured ) shows that, on the contrary, anyone can increase their cool quotient by learning from the masters and the methods of the past.It's never an easy journey. But to set yourself on the path to true cool, you'll need this invaluable roadmap.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access How to be Cool by Thomas W Hodgkinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Popular Culture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE:

IDOLS

This isn’t a list of the 75 coolest people who ever lived. I think I probably need to repeat that, because admittedly, it’s what it looks like: but this is not a list of the 75 coolest people in history. I could try to write that list, but it would be completely subjective, and tell you far more about me than anything else. If that’s your wayward interest, Part Three caters to your whim.

No, what this is, or aims to be, is a list of the 75 people who have contributed most to defining or refining our idea of what ‘cool’ has come to mean. It should really be entitled ‘Idols and Idolaters’ since it includes ‘cool-chasers’ such as Quentin Tarantino and David Bailey, more notable for whom they perceive to be cool than for their own coolness (though neither does too badly). There’s also the laboriously uncool Norman Mailer, included because he wrote an important essay on the topic. And one or two others whose reputation baffles, but who seem – who knows how? – to loom large in the imagination, once the mind starts skimming over the landscape of cool.

William Blake, poet and artist (1757–1827)

You’ve got to start somewhere. And if you take William Blake to be one of the fathers of the Romantic movement, and accept that the Romantic movement – which prioritised rebellious feeling over conventional common sense – was an important forerunner for the rise of cool, then the life and personality of William Blake seem as good a place to start as any. Add to that the fact that the poet Allen Ginsberg*, one of the founders of 1960s countercultural cool, idolised him, and is said to have enjoyed a series of ecstatic epiphanies while reading Blake’s poetry and masturbating, then that settles it. We had better start with Blake.

The man was a visionary, and that’s not meant loosely or lazily, but in the literal sense. He actually saw visions of angels and demons, whom he would paint in oils (the extraordinarily sinister sketch ‘The Ghost of a Flea’ is an example) and address in his verse. He was, after Michelangelo, the greatest poet-painter in history, and one of the few really important British visual artists. He was also widely believed to be barking mad, although the evidence for this largely consists of those diverting or disconcerting visions:

Tiger, tiger, burning bright, In the forest of the night …To see the world in a grain of sand, And a heaven in a wild flower …Love seeketh only self to please, To bind another to its delight …

These sonorous phrases all flowed from Blake’s pen, highlights to poems of flickering brilliance, which, although little read in his lifetime, with the benefit of hindsight can be seen to be worth whole cantos of Byron’s* bestsellers. Strangely enough, the man’s best-known lines today are the lyrics to the hymn ‘Jerusalem’ (‘And did those feet in ancient time …’). What’s curious about it is that the mind behind these patriotic-sounding sentiments was in fact passionately anti-monarchist.

Blake’s unconventional views were one reason for his obscurity in his lifetime, and also for the attraction he held in the mid-20th century for the likes of Ginsberg, who worshipped him not only for his rebelliousness, but also as a prophet of free love. Blake’s poem ‘The Garden of Love’ imagines the ministers of organised religion ‘binding with briars my joys and desires’. Yet these apparently hippyish views were not pursued in practice. A mainstay of the poet’s life was his wife Catherine, to whom he was faithful for 45 years.

Beau Brummell, dandy (1778–1840)

Lord Byron* once remarked that there were three great men of his era: himself, Napoleon and Beau Brummell – but the greatest of these was Brummell. What was his drift? Brummell wrote no poetry worth reading. He led no armies into battle. He is mainly credited with having popularised trousers. And ties. And three-piece suits. But to be fair, this did constitute a complete rewriting of the rules of fashion. Before Brummell, men had worn elaborate wigs and flashy clothing. This, he declared, was absurd. On the contrary, the aim should be to dress as simply as possible but with scrupulous attention to detail. This has been the shimmering ideal of male fashion ever since.

Picture Oscars night. You can see all the women in their diaphanous or soigné outfits, with the plunging necklines and backlines, and the twills and the frills and the gimmicks. (There goes Björk* in her infamous ‘swan dress’.) Yet the strange thing, if we weren’t so used to it, is that the men are all dressed more or less identically in sleek black dinner jackets. That’s Brummell’s legacy. He was known as a ‘dandy’, which originally meant a man who dressed in a plain style, albeit one that was achieved by a vast concentration of effort. The story goes – although it presumably cannot have been true – that every day he spent five hours getting ready before venturing out of doors.

A dandy is also someone who elevates the art of dressing to a life philosophy. The implication is that your clothes aren’t designed to decorate you. They are you. It doesn’t matter if you’re not from a posh or wealthy family. If you’re the best-dressed man in the room, you’re the best man in the room, and everyone else can go to hell. This may seem a little superficial, but it was actually revolutionary at a time when worth was more generally determined by breeding.

Brummell, who was from a middle-class background, earned the admiration of the dim, plump Prince of Wales with his daring style and insolent, insouciant manner. This is one of the man’s main claims to being a forerunner to 20th-century cool: he was dispassionate, rude, and often very funny in his deliberately outrageous attitudes. When someone asked him if he really restricted his diet to meat and bread, or if he ever indulged in vegetables, he confessed, ‘I once ate a pea.’ Another time, a friend of his noticed that he had a limp. ‘I hurt my leg,’ Brummell explained sadly. ‘The worst of it is, it was my favourite leg.’ Eventually his inability to resist a sharp one-liner led to his downfall. The sulky Prince snubbed him at a party, and Brummell declared loudly to his neighbour, ‘Who’s your fat friend?’ Denied royal patronage, he fell into debt and died in a French asylum, penniless and insane from syphilis. Nevertheless, if you are intent on ruining your life, publicly insulting the heir to the throne is a pretty cool way to do it.

Lord Byron, poet (1788–1824)

Forget the poetry and the prose. In Lord Byron’s case, it was all about the pose. Club-footed; as handsome as hell; an aristocrat who disdained rank. A ladies’ man with an interest in young boys. The darling of society, who shunned its invitations. A genius with a secret. A rake-hell. A hero. The important point wasn’t really whether the young baron was all or some of these things, but that they were his reputation. For the ‘Byronic’ character type he pioneered, both in verse and in person, was hugely influential in the 19th century and became a template for cool in the 20th.

This didn’t come about by accident. A lifelong self-dramatist, Byron cultivated his image to such an extent that it’s hard to tell in retrospect when his behaviour was the product of a bipolar personality and when it was deliberately put on with the aim of sealing his legend. After an artist once sculpted him, Byron complained, ‘That is not at all like me. I look much more unhappy.’ He used to sleep with his hair in curlers to preserve his mop of tousled locks. He also wrote endless B-movie-style narrative poems about Byronic heroes, often pirates*, who swagger around hinting at diabolical secrets in their past. Inevitably, his horde of readers speculated that he was writing about himself, which of course he was. Or rather, he was writing about himself as he wished to be perceived.

He married his wife, Annabella, for her money, and then treated her viciously. She issued divorce proceedings against him after a year, on the grounds of various sexual perversions, including an unproven but probable incestuous affair with his half-sister, Augusta. Byron fled England, never to return. This rather suited him. He was, if anything, even more popular on the continent. He wrote horror stories with Shelley on Lake Geneva, had a ball in Venice with a series of Italian hotties, and finally, in a wild attempt to invest his dissolute life with purpose, sailed to Greece to fight against the Turks in the cause of freedom. In the event, he caught a fever and died at the age of 36.

Sarah Bernhardt, actress (1844–1923)

The playwright Oscar Wilde once asked the actress Sarah Bernhardt, ‘Do you mind if I smoke?’ ‘I don’t mind if you burn,’ she replied. Although it’s probably too good to be true, this serrated riposte captures the essence of Bernhardt’s devil-may-care reputation. She wasn’t particularly beautiful, but enjoyed a string of affairs with everyone from the novelist Victor Hugo to the Prince of Wales. As an actress, she had a rather hammy style and a weak, breathy voice. Yet through sheer charisma she earned the reputation of being the greatest actress of her era. Or as the novelist Mark Twain put it, there are ‘good actresses, great actresses, and then there is Sarah Bernhardt’.

Henry James may have been closer to the mark when he described her as a genius at self-promotion. Her first publicity coup came in 1862 when, as a young actress struggling to make her name on the Parisian stage, she called the leading lady a ‘miserable bitch’ and slapped her face. By the end of the week, she was out of a job, but everyone knew who she was. A lifelong fabulist, the Divine Sarah, as many called her, sustained her celebrity by telling outlandish stories about herself and behaving with ostentatious eccentricity. She liked to sport a hat adorned with a stuffed bat, and kept a tame alligator she called Ali-Gaga. She also developed an odd habit of sleeping in coffins, explaining that it helped her to get to grips with her more morbid tragic roles. Her choice of those roles also seems self-conscious. Her decision to play Hamlet*, for instance (one of the most challenging male characters in the theatrical repertoire), was itself a feminist statement, while her penchant for biblical parts was deliberately designed to shock.

Her legacy rests as much on her personal style – in particular, the display she made of not giving a damn – as it does on her dubious thespian skills. While touring in England, she made no effort to disguise the illegitimacy of her son at social events. On the contrary, she asked that on entering a room the two of them should be announced as ‘Mlle Bernhardt, and her son’. That got the point across. To any questioning or criticism of her behaviour, the Divine Sarah tended to reply with a Gallic shrug and the phrase ‘Quand même.’ This loosely translates as, ‘Do I look like I care?’

Arthur Rimbaud, poet (1854–91)

He was Bob Dylan’s* favourite poet. Henry Miller was a fan. The three principal Beatniks*, Jack Kerouac*, William Burroughs* and Allen Ginsberg*, were all crazy about him. So what was it about the decadent French poet Arthur Rimbaud that got them pumped? After all, he was clearly a total bastard. What else can you conclude about someone who, on one occasion, defecated on a café table because he was bored, and on another, added sulphuric acid to someone’s drink as a joke?

One reason why he has met with such passionate admiration is that he managed to write brilliant poetry while off his head on opium, absinthe and other stimulants. The implication is that he may have written so well because he was off his head, which therefore provides a useful pretext for other writers to get off their heads, too. It has to be admitted that Rimbaud himself believed there was a causal link between intoxication and inspiration. In a letter he wrote to a friend when he was seventeen, he declared that the poet who wishes to become a visionary must do so by what he called the ‘long, immense et raisonné dérèglement de tous les sens’: which is to say, a ‘vast, sustained and deliberate disruption of all the senses’. Rimbaud believed that, in the case of the great Ancient Greek poets, verse had arisen directly from the soul, whereas the writers of his day, by contrast, were merely playing pompous artificial literary games. The best way to prise oneself free of these disgraceful conventions, Rimbaud argued, was by getting wrecked, and that is what he did.

Running away from his tediously provincial home at sixteen, he threw himself into a life of artistic decadence, which centred on a violent homosexual relationship with the poet Paul Verlaine, who eventually tried to kill him but only succeeded in shooting him in the wrist. None of this would be of much interest if Rimbaud had written bad poetry. To his fans, his easy early stuff (e.g. Le Dormeur du val, in which someone you think is asleep turns out to be dead) and his later, harder style (for instance, the autobiographical prose poem Une Saison en enfer) are both in their different ways indispensable. Having said all he had to say, Rimbaud put down his pen at the age of twenty and literally never wrote another poem. Instead he travelled to Abyssinia, where he worked as a coffee merchant and gun runner. This is one of the things that most astonishes about Rimbaud: that he packed two such different lives into such a short span. He died of bone cancer at the age of 37.

Isadora Duncan, dancer (1877–1927)

The sculptor Auguste Rodin described her as ‘the greatest woman the world has ever known’. The choreographer George Balanchine was less impressed. He remembered ‘a drunk fat woman … rolling around like a pig’. Doubtless the two men saw the American dancer Isadora Duncan at different stages in her career, since in later life she lost the lithe figure she’d honed as a girl growing up in California, and became rather rotund. A compulsive rebel, she rejected the present (describing the ballet of her day as ‘sterile gymnastics’) in favour of the past – specifically the ideals associated with the culture of Ancient Greece. Here, she was convinced, would be found the essence of dance, in its origins as a sacred act. She spent long hours in the British Museum in London, scrutinising the dancers depicted on Ancient Greek vases. Combining inspiration from this and other sources (for instance, the motion of the sea), she developed her system of ‘natural movement’, which would form the bedrock of modern dance.

Freedom was her watchword. Freedom of movement: she performed barefoot and in flowing Hellenic-style clothes, which afforded appreciative fans the sight of her bare legs and an occasional flash of bosom. Freedom of political expression: on stage in Boston, she declared her sympathy with Communism by baring one breast and waving a red scarf, shouting, ‘This is red and so am I!’ And freedom of sexuality: she produced two children out of wedlock, and had affairs with both men and women, including the alcoholic Russian poet Sergei Esenin, and the poet and playwright Mercedes de Acosta (who would later enjoy a relationship with Greta Garbo*).

All of which is a roundabout way of saying that Duncan was one of the original hippies. In a macabre twist, however, her devotion to freedom led to her death in grotesque circumstances. In 1927, in Nice, she climbed into a car with a young car mechanic she fancied, threw a long and flowing scarf over her shoulder, and declared, ‘Adieu, mes amis! Je vais à la gloire!’ (Goodbye, my friends! I go to glory!) It’s a terrific parting shot for almost any situation, but it doesn’t make much sense in this case. More likely, as some have reported, what she actually said was, ‘Je vais à l’amour!’, referring to the way she hoped her evening would pan out. As the ...

Table of contents

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- About the author

- Acknowledgements

- Cool: An Introduction

- Part One: Idols

- Part Two: Ideas, Ideals and Other Cool S***

- Part Three: The Real Deal

- Appendix: The Cool Test

- Index

- Back Cover