eBook - ePub

The Dragon in the Cockpit

How Western Aviation Concepts Conflict with Chinese Value Systems

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Dragon in the Cockpit

How Western Aviation Concepts Conflict with Chinese Value Systems

About this book

The purpose of The Dragon in the Cockpit is to enhance the mutual understanding between Western aviation human-factors practitioners and the Chinese aviation community by describing some of the fundamental Chinese cultural characteristics pertinent to the field of flight safety. China's demand for air transportation is widely expected to increase further, and the Chinese aviation community are now also designing their own commercial aircraft, the COMAC C-919. Consequently, the interactions in the air between the West and China are anticipated to become far more extensive and dynamic. However, due to the multi-faceted nature of Chinese culture, it is sometimes difficult for Westerners to understand Chinese thought and ways, sometimes to the detriment of aviation safety. This book provides crucial insights into Chinese culture and how it manifests itself during flight operations, as well as highlighting ways in which Western technology and Chinese culture clash within the cockpit. Science and technology studies (STS) have demonstrated that sophisticated technologies embed cultural assumptions, usually in subtle ways. These cultural assumptions 'bite back' when the technology is used in an unfamiliar cultural context. By creating the insider's perspective on the cultural/technological assumptions of the world's fastest growing industrial economy, this book seeks to minimize the accidents and damage resulting from technological/cultural misunderstandings and misperceptions.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Tragedy in Nagoya

“Be careful! Guard and cover the memorial tablet! The souls cannot be touched by the sunlight!”

A high and clear voice appeared in Taipei Chiang-Kai-Shek (CKS) International Airport (CKS), as airport officials brought along a group of big black umbrellas (United Daily News, April 29, 1994). It was 3 o’clock in the afternoon, the sun dazzled in the sky. There was one victim each covered under the Each victim was covered by a big black umbrella, and with a heartbroken family behind. Just a few days earlier, a plane crashed in Nagoya Airport, Japan. The cremated remains of 67 victims were carried back to Taipei together with 30 coffins, and the reception site for the dead was set up right in the airport. Airline company staff held high a white long cloth, waving to and fro against the wind, written on it with large black characters: “China Airlines staff begged for forgiveness from victims’ families,” bowed and apologized with deep sorrow and regret again and again …

On April 26, 1994, two Taiwanese pilots flew an Airbus A300-600R automatic airplane from CKS International Airport to Nagoya, Japan. There were 256 passengers, 13 cabin members and two pilots, 271 people in total on the plane. The plane took off smoothly from CKS Airport on schedule; two pilots followed the designated route according to the plan, heading to Nagoya Airport, Japan.

At 8:07pm (20:07), the airplane prepared to land on runway 34 under guidance from the approach tower and the instrument landing system (ILS). At 8:12pm, the plane passed the outer beacon with altitude roughly above 2,000 feet. The plane followed the three-degree glide path marked by the ILS to execute the standard landing procedure. Everything was normal. Two minutes later, when the plane was flying just below 1,000 feet, it started to level off, as if it didn’t want to land. Yet, no additional sign showed that the plane was starting to climb to go around, which is a standard maneuver in a missed landing. After 15 seconds of level flight, the plane started to descend. At this moment, the plane was only 800 feet above the ground, and the speed was only 146 knots, yet well above the stall speed of 110 knots.

The plane descended steadily again, and everything seemed back to normal. At 8:15pm, the plane continued descending for about 30 seconds, reaching 350 feet above the ground. It looked like the giant was about to land. Yet suddenly, a deep and loud roar came out from the engine, the thrust was suddenly elevated to the maximum. The nose started to level off, and the plane surprisingly started to climb with increasing speed. It happens once in a while that a plane cannot land smoothly in the very final stage of landing, and has to execute a “go-around,” a standard maneuver. However, it did not look like this plane was going around, because the pitch of the plane was still increasing, eventually to 50 degrees!

The wing stalled, the lift dropped drastically, and the drag increased significantly. Unfortunately, the thrust from the engines was not enough to raise the plane by itself. A chain of abnormal events combined and pushed the altitude back to 1,500 feet, with the speed suddenly declining to only 87 knots. The speed was already significantly lower than the stall speed. The plane started to fall out of the sky.

In less than one and half minutes, the situation facing the plane evolved from a three-degree steady descent on landing procedure to an irreversible situation beyond human control. The aircraft lost lift, its drag increased, its thrust was less than normal, its altitude increased, and its speed dropped. The entire situation made the plane totally out of control.

Two years later, the Japanese authority released the accident report (Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission, Ministry of Transport, Japan, 1996). The report pointed out that there was no clear sign of mechanical malfunction or special meteorological factors. In other words, the accident could only be attributed to human factors of the flight crew.

According to the accident chain theory from Boeing (Boeing Commercial Airplane Group, 1994), the Ministry of Transport of Japan listed every single link showing the evolving sequence in the accident:

1. The first officer (F/O) inadvertently triggered the go lever activating the go-around procedures.

2. The F/O continued pushing the control wheel in accordance with the instructions of the captain (CAP) in order to continue the approach.

3. The movement of the trimmable horizontal stabilizer (controlled by the computer) conflicted with that of the elevator (controlled by the crew), causing an abnormal out-of-trim situation.

4. There was no warning and recognition function to alert the crew directly and actively to the onset of the abnormal out-of-trim condition.

5. The CAP and F/O did not sufficiently understand the flight director mode change and the autopilot override function.

6. The CAP’s judgment of the flight situation while continuing approach was inadequate, control takeover was delayed and appropriate actions were not taken.

7. The alpha-floor function was activated. This was incompatible with the abnormal out-of-trim situation, and generated a large pitch-up moment. This narrowed the range of selection for recovery operations and reduced the time allowance for such operations.

8. The CAP’s and F/O’s awareness of the flight conditions, after the CAP took over the controls and during their recovery operation, was inadequate respectively.

9. Crew coordination between the CAP and F/O was inadequate.

The alpha-floor function is an automatic protection to prevent the plane from stalling. When the angle of attack of the plane reaches 11.5 degrees, close to stall, the flight control system will automatically open the throttle to the limit and lock, pushing the thrust to the maximum and speeding up the plane, so as to escape from the danger of stall.

The accident report made some recommendations to Airbus and the airline:

To Airbus:

1. Improvement of the override function, out-of-trim prevention and warning and recognition functions for the trimmable horizontal stabilizer of the automatic flight system of the A300-600R is required.

2. The descriptions of override, disengagement of go-around mode and recovery procedures from out-of-trim in the Flight Crew Operation Manual of the A300-600R should be improved from the operational viewpoint.

3. In the event of an accident or serious incident, Airbus Industrie should promptly disseminate the systematic explanation of its technical background to each operator, and furthermore should positively and promptly develop modifications.

To the airline:

1. Reinforcement of education and training programs for flight crews;

2. Establishment of appropriate task sharing;

3. Improvement of crew coordination;

4. Establishment of standardization of flight.

Stated simply, this accident was caused by the conflict between the pilots and the automatic flight control system. The flight crew were fighting for control over the plane! In other words, the pilot pushed the plane to land, the computer managed to go around, and both wouldn’t let go.

In fact, similar incidents had taken place before, incidents that weren’t severe enough to cause planes to crash. Airbus has also released a notice, warning the pilots not to try to override the automatic flight control system. However, Airbus hasn’t really made any change to the design of this protection system, apparently judging that this was not a serious matter. According to the experts at Airbus, the way out from such an abnormality is simply to release control of the airplane, so that the automatic flight control system can take over and execute the go-around procedure up to around 3,000 to 4,000 feet above ground level.

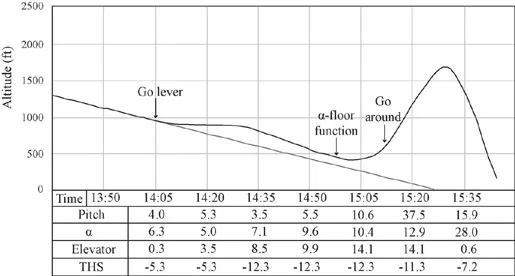

Figure 1.1 (below) shows the final flight profile of the Nagoya accident. According to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), similar to what was pointed out by the Japanese accident report, there wasn’t any problem with the machine, and the automatic flight control system did everything according to the order, rejecting the override from manual control and executing go-around. Almost everyone agreed that this accident was caused by human factors.

Figure 1.1 The final flight profile of the Nagoya accident

For example, the F/O wrongly controlled the plane and the crew did not fully understand the functions of the automatic flight system. Hence, the corresponding solution is to emphasize the out-of-trim training to the pilots, just as suggested by the Transport Ministry of Japan.

But is this a sufficient explanation? Will similar incidents be prevented from happening again after enough training?

The primary goal of accident investigation is to find the real causes behind an accident, make recommendations, and ideally prevent similar events from happening again. However, after the Nagoya accident, in less than four years, an almost identical accident took place. The same type of aircraft crashed in almost the same manner in Da-Yuang, Taiwan. It forced us to think: have we indeed found the real cause of the Nagoya accident? And have the suggestions from the accident investigation report really mitigated the conflict between the pilots and the computer?

Every single human behavior has its origin. Some are after deliberate consideration belonging to the decision-making behavior. Some are from a cultural heritage that is shared within a community, some are from the sub-consciousness, perhaps even instinct. Behavior that appears on the surface to be the same might originate from completely different sources. If we insist on looking at only what it appears to be, and do not dig deep and get at the real cause behind such a behavior, how can we recommend an effective solution? Obviously, the principal beliefs widely accepted by the international aviation community might very likely bring about a self-restricting situation, causing the truth to be buried.

The cockpit voice recorder (CVR) is an essential resource for finding human errors. Further, the CVR can supply hints about the psychological conditions, even cultural characteristics, of the crew. The sequence of the Nagoya accident clearly shows the disastrous interaction between the pilots and the machine. How could the interaction become so fatal? What was in the crew’s mind? What were the pilots thinking during the process? The main part of the conversation of the crew was in Chinese. Hence, it requires a thorough knowledge of Chinese language and culture, preferably by one sharing a similar cultural background, in order to have a thorough understanding of the real meaning of the conversation.

After the F/O inadvertently triggered the go lever, at the same moment the CAP reminded the F/O of the situation.

20:14:10 CAP: You, you triggered the go lever.

20:14:11 F/O: Yes, yes, yes. I touched a little.

At that time, the automatic flight control system started to execute the go-around procedure, and the plane began to level off. Yet the crew still wanted to land, so the F/O continuously pushed the control yoke, hoping to lower the nose. The angle of the elevator increased.

The CAP acknowledged the situation and commanded the F/O to disengage it.

20:14:12 CAP: Disengage it!

Immediately, the cockpit voice recorder recorded the sound of a pitch trim maneuver. Obviously the F/O was pushing the yoke and trimming the pitch, trying to disengage the automatic go-around which was already in progress, so that the plane could continue to land. However, the order that the computer received was to go around, so in order to raise the nose, the angle of the trimmable horizontal stabilizer started to rotate, countering the effect from the increase of the angle of the elevator. The elevator and the horizontal stabilizer started to diverge and their angles differed even more. The two control surfaces of the tail that should cooperate to fly the airplane actually started to go against each other.

Two contradictory orders continued to take effect on the horizontal stabilizer. After 20 seconds had passed, the CAP reminded the F/O that the plane was still in go-around mode, indicating that both of the crew recognized the go-around mode was still on.

20:14:30 CAP: You, you are using the go-around mode.

20:14:34 CAP: It’s OK, disengage again slowly, with your hand on.

Then, the sound of pitch trim is heard continuously without a break five times, indicating that the F/O was still trying to disengage the autopilot and continue descending. Unfortunately, he was continuously trying the same ineffective maneuver. And on the contrary, it caused the out-of-trim situation, i.e., the conflict between the elevator and the horizontal stabilizer, to become even worse.

Since the CAP reminded the F/O that the go lever was triggered, 24 seconds had passed. During this time, the F/O had tried six times to disengage, yet in vain. Strangely, he never tried to speak out that he could not resolve the problem. Nor did he express that he did not know how to do it. According to the accident report, obviously the F/O didn’t know the correct procedure, yet he refused to speak out or to ask, just continued trying the same ineffective maneuvers.

Several seconds later:

20:14:41 CAP: Push more, push more, push more.

20:14:41 F/O: Yes.

20:14:43 CAP: Push down more!

Of course it was still ineffective:

20:14:45 CAP: It is now still in go-around mode.

F/O: Yes, sir.

The CAP reminded the F/O again that the plane was still in go-around mode. Several seconds later:

20:14:51 F/O: Sir, I still cannot push it down.

Strangely, another several seconds passed without any response from the CAP.

20:14:58 CAP: I, well, land mode?

Obviously, the CAP was asking the F/O if the go-around mode had been switched to the land mode, but the F/O remained silent. Another several seconds later:

20:15:01 CAP: It’s OK. Do it slowly.

Yet right after he comforted the F/O, the CAP couldn’t stand anymore and said:

20:15:03 CAP: OK, I have got it, I have got it, I have got it.

The CAP finally took over the control without waiting for the F/O to complete the disengagement of go-around. Yet the alpha-floor protection function had been activated. The throttle of the engine had gradually increased to the maximum. Since the action line of the thrust passes under the wing, right beneath the center of gravity of the plane, the increase of the thrust force resulted in a positive pitching movement. The nose was raised quickly, causing the pitch of the plane to further increase.

What happened next was really frightening:

20:15:08 CAP: What’s the matter with this?

The F/O also panicked:

20:15:09 F/O: Disengage, dis …

The nose continued to pitch up, and the plane climbed further up.

20:15:11 CAP: Go level.

Damn it, how come like this?

Damn it, how come like this?

Surprisingly, the CAP also did not know how to disengage the go-around! Meanwhile, the CVR recorded the sound of pitch trim twice. The CAP was trying exactly the same ineffective action that the F/O had already tried six times.

The pitch angle of the plane had been raised up to 21.5 degrees now, and was still increasing. The signs of an unusual and dangerous situation were very clear, so the F/O immediately called to the tower to prepare to go around.

20:15:14 F/O: Nagoya Tower, Dynasty going around.

Seconds later, the sound of flap movement was heard, the ground proximity warning system alarmed at the same time, and the angle of the airplane pitched up to 36.2 degrees. Facing such a frightening situation they had never experienced before, both of the crewmembers froze.

20:15:21 CAP: If this goes on, it will stall.

20:15:25 CAP: Finish.

In Chinese, this word means, “We’re screwed.” The stall warning went off, and the pitch angle reached an unbelievable 52.2 degrees.

20:15:26 F/O: Quick, push nose down.

In the cockpit, the atmosphere was extremely chaotic, all kinds of warnings and operational sounds clashed all together.

20:15:31 F/O: Set, set, push nose down.

The plane started to fall after it peaked to the highest.

20:15:34 CAP: It’s OK, it’s OK!! Don’t, don’t hurry. Don’t hurry.

F/O: Power!!

The plane started to fall faster and faster … the crew was obviously terrified.

20:15:37 CAP: Ah …!!

F/O: Power, power, power!!

Until the end of recording, the CVR was full of frightened screaming. The CVR recorded deadly silence at 20:15:45. The runway of Nagoya Airport was already covered by a stretch of raging fire.

In earlier ages, there was not much computer technology used in airplanes. How the airplane flew was mainly affected by the aerodynamic features of the corresponding mechanical system itself. Even if the pilots were not fully familiar with the aerodynamic features of the plane, it would not have been a big problem because the airplane was not going to do anything by itself. As airplanes became more and more complex, together with the rapid development of computer tech...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- 1 Tragedy in Nagoya

- 2 Technology, Language, and Culture

- 3 Fundamental Features of Taiwanese Accidents

- 4 A Chinese Viewpoint of Western Culture in Aviation Safety

- 5 Descendants of the Dragon

- 6 Measuring Chinese Authoritarianism in the Cockpit

- 7 We Are All in One Family

- 8 Guanxi Gradient

- 9 A Struggle of Two Mindsets

- 10 Flight Safety Margin Theory

- 11 A Harmonious Sky through Compatibility

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Dragon in the Cockpit by Hung Sying Jing,Allen Batteau in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Aeronautic & Astronautic Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.