![]()

Part 1

![]()

1 Language and Identity in Multilingual Schools: Constructing Evidence-based Instructional Policies

Jim Cummins

Since the mid-1990s, educational underachievement among immigrant and other marginalized social groups has increased in significance for policy-makers in many countries because of the demonstrated relationship between education and national development in a knowledge-based economy. This relationship motivated the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to initiate the Programme for International Student Achievement (PISA) which provides member countries with a ‘report card’ on the effectiveness of their educational systems, including the relative success of students from immigrant backgrounds. PISA has highlighted the extent of immigrant students’ underachievement in many affluent countries and also the considerable variability across countries in the extent to which these students succeed academically. This chapter analyses the ways in which the PISA data and other research findings have been incorporated into educational policy in the Canadian and United States contexts. In both contexts, there exists a considerable gap between policies and research evidence. Specifically, there has been little consideration given to the role of societal power relations and their manifestation in patterns of teacher–student identity negotiation. Policy-makers have also largely ignored research related to the role of immigrant students’ first language as both a cognitive tool and a reflection of student identity. Finally, little attention has been paid to the importance of reading engagement which has consistently emerged in the PISA research as a major determinant of reading achievement. The chapter outlines an empirically-based theoretical framework that explicitly addresses the roles of literacy engagement and identity negotiation as determinants of student achievement.

Introduction

Underachievement among immigrant and other minority group students is by no means a recent phenomenon. Students from groups that have experienced persistent discrimination in the wider society over several generations are particularly vulnerable to educational failure (Ogbu, 1992). In the United States context these groups include African American, Native American and Latino students. In Europe, Roma and Traveller communities as well as more recent immigrant communities have experienced widespread discrimination, which is reflected in students’ educational performance. Schools tend to reflect the values of the societies that fund them and thus it is not surprising that societal discrimination is frequently also reflected within the educational system. This discrimination expresses itself both in the structures of schooling (e.g. curriculum and assessment practices) and in patterns of teacher–student interaction. The subtle ways in which societal biases express themselves in patterns of teacher–student interaction are illustrated in a large-scale study conducted by the US Commission on Civil Rights (1973) in the American southwest. Classroom observations revealed that Euro-American students were praised or encouraged 36% more often than Mexican-American students and their classroom contributions were used or built upon 40% more frequently than those of Mexican-American students.

The link between societal discrimination and school performance was clearly expressed in the judgment of the federal court in the United States versus the State of Texas (1981) case which documented the ‘pervasive, intentional discrimination throughout most of this century’ against Mexican-American students (a charge that was not contested by the State of Texas in the trial). The judge noted that:

the long history of prejudice and deprivation remains a significant obstacle to equal educational opportunity for these children. The deep sense of inferiority, cultural isolation, and acceptance of failure, instilled in a people by generations of subjugation, cannot be eradicated merely by integrating the schools and repealing the ‘no Spanish’ statutes. (1981: 14)

Indigenous communities throughout the world have similarly experienced ‘generations of subjugation’, which is also manifested in poor school performance. In the Canadian context, for example, First Nations and Inuit students were taken from their communities, often against their parents’ will, and placed in residential schools operated by religious orders. The physical, sexual and psychological abuse that occurred in these schools has been well-documented. Eradication of Native identity was seen as a prerequisite to making students into low-level productive Christian citizens.

This brief historical sketch of the educational experiences of minority group students illustrates one of the main themes of this chapter, which can be stated as follows:

The academic achievement of minority group students is directly influenced both by the structures of schooling, which tend to reflect the values and priorities of the dominant group, and by the patterns of identity negotiation students experience in their interactions with educators within the school. Teacher–student interactions are never neutral – in contexts of social inequality these interactions either reinforce the devaluation of minority group culture, language and identity in the broader society or they challenge this devaluation. This implies that in order to reverse underachievement among minority group students, classroom instruction must affirm students’ identities and challenge patterns of power relations in the broader society.

Efforts to reverse underachievement among low-income and minority group students were initiated in several countries during the 1960s, motivated primarily by renewed commitment to equity and social justice. These efforts have met with limited success. For example, data from the United States show that the achievement gap between low-income and more affluent students and between Euro-American and most groups of minority students remains large (Darling-Hammond, 2010).

However, during the past 15 years, educational underachievement has assumed greater significance for policy-makers in many countries because of the demonstrated relationship between education and economic development in a knowledge-based economy. The economic implications of increasing diversity derive from the fact that immigrants represent human capital, and school failure among any segment of the population entails significant economic costs. The relationship between education and the economy motivated the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to initiate the Programme for International Student Achievement (PISA), which provides member countries with a ‘report card’ on the effectiveness of their educational systems, including the relative success of first- and second-generation immigrant students. The PISA research has highlighted the extent of immigrant students’ underachievement in many affluent countries (e.g. Germany, the United States) and also the considerable variability across countries in the extent to which these students succeed academically (Christensen & Segeritz, 2008; Stanat & Christensen, 2006).

An economic growth projection published by the OECD (2010a) estimated that even minimal improvements in the educational performance of socio-economically disadvantaged students would result in very significant long-term savings for member countries. OECD projections suggest that a 1% increase in adult literacy levels would translate into a 1.5% increase in a country’s gross domestic product, which, in Canada’s case, would amount to $18 billion per year (Coulombe et al., 2004). Thus, it is not surprising that the relatively poor literacy performance on the PISA tests by 15-year old first- and second-generation immigrant students in many of the more affluent European countries has given rise to intense debate about how to improve students’ literacy skills.

Efforts to improve school achievement in general and among any segment of the school population are always premised on hypotheses regarding the causes of underachievement. Unfortunately, in many cases, these hypotheses derive more from ideological convictions than from rigorous analysis of the empirical data. This reality is not altogether surprising; there are obvious ideological complexities associated with social policies generally, and particularly with respect to issues of equality, income distribution, immigration and priorities within public education systems. Consequently, ideological presuppositions frequently influence what research is considered relevant and how that research is interpreted.

In this chapter, I attempt to critically assess the extent to which educational policies in relation to immigrant students (and minority group students more generally) are based on empirical evidence. In the first section, I review the outcomes for immigrant students in the 2003 and 2006 PISA studies and the recommendations for educational reform that have been made on the basis of these data. I then present an alternative analysis of the causal factors underlying the underachievement of certain groups of immigrant and minority students that draws on a wider range of research data than has typically been considered in relation to the PISA data. Finally, I examine the extent to which relevant research findings have been incorporated into educational policy in two national contexts: Canada and the United States. In each context, there exists a considerable gap between policies and research evidence. In no case have considerations related to teacher–student identity negotiation or patterns of societal power relations been explicitly integrated into causal or intervention frameworks despite the extensive research evidence attesting to the significance of these factors. By the same token, policy-makers have largely ignored research related to the role of migrant students’ first language (L1) as both a cognitive tool and a reflection of student identity. The absence of identity negotiation and power relations from policy consideration is particularly notable given the prominence of these constructs in recent applied linguistics research and theory focused on second language learning and literacy development (see, for example, the review by Norton & Toohey, 2011).

Patterns of Immigrant Student Achievement

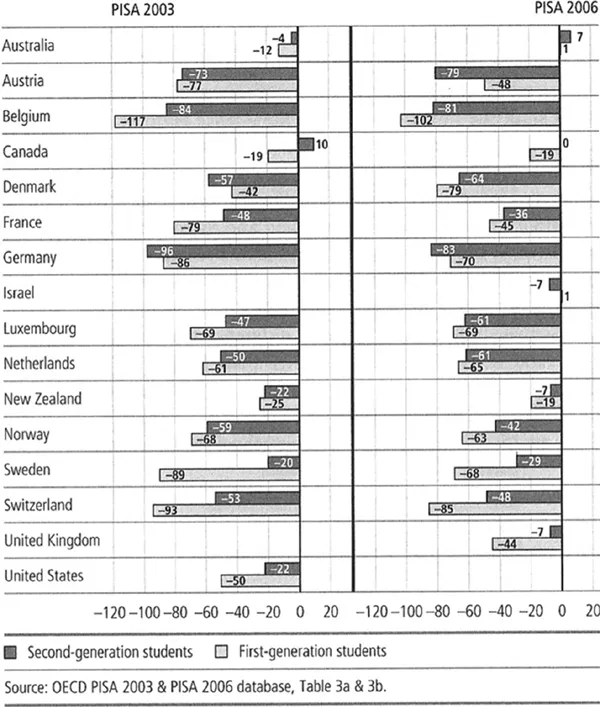

The 2003 and 2006 PISA reading achievement of 15-year-old first- and second-generation immigrant students in 15 countries is presented in Figure 1.1. Christensen and Segeritz (2008: 15) summarize the overall pattern of results as follows:

With regard to reading, first- and second-generation students lag significantly behind their native peers in all of the assessed countries, except Australia and Israel, and second-generation students in Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

The PISA data reveal major differences between countries in how well first- and second-generation immigrant students are doing in school. Students’ performance tends to be better in countries such as Canada and Australia that have encouraged immigration over the past 40 years and that have a coherent infrastructure designed to integrate immigrants into the society (e.g. free adult language classes, language support services for students in schools, rapid qualification for full citizenship, etc.). In Canada (2003 assessment) and Australia (2006 assessment), second-generation students performed slightly better academically than native speakers of the school language. Some of these positive results in both countries can be attributed to selective immigration that favours immigrants with strong educational qualifications. First-generation immigrant students in Ireland exhibit relatively strong performance parallel to the patterns in Canada and Australia, which is likely related to the minimal differences in socioeconomic status between immigrant and native-born students (OECD, 2010b).

Christensen and Segeritz (2008: 18) point out that the poor performance of second-generation students in many countries should be a cause of concern to policy-makers: ‘Of particular concern, especially for policy-makers, should be the fact that second-generation immigrant students in many countries continue to lag significantly behind their native peers despite spending all of their schooling in the receiving country.’

Figure 1.1 PISA Reading scores 2003 and 2006 (from Christensen & Segeritz, 2008: 16)

Barth and colleagues (2008), in commenting on the PISA data, identify some of the dimensions along which both policy-makers and educators can implement effective instruction for a diverse student body. Obviously, providing language support and an inclusive curriculum that integrates language and content are core elements. However, they also emphasize the necessity for schools to view diversity as a resource and to establish respectful collaborative partnerships with parents and the community. The OECD (2010b) also highlights the importance of capitalizing on the resources of immigrant communities and valuing and validating students’ proficiency in their mother tongues. Little (2010) has expressed a similar perspective which is reflected in Council of Europe initiatives in this area: ‘The language, ethnicity and culture that children and adolescents from migrant backgrounds bring to school are assets that must be exploited first for their own benefit as individuals and then for the benefit of the larger school community’ (2010: 31).

However, this emphasis also highlights a major challenge for implementing educational change. As noted earlier, schools reflect the values and priorities of the societies...