![]()

1Wanted: Well-Trained ESL Teachers

The United States is in the midst of two profound demographic shifts. On the one hand, the US population is becoming more ethnically and racially diverse, a transformation driven mostly by immigration and higher birth rates among some groups. On the other hand, the US population is getting considerably older as the massive baby boom generation moves into retirement. In this chapter, I explore the social and educational implications of these demographic changes. In particular, I describe the growing need for well-trained English as a second language (ESL) teachers in both K-12 and adult classrooms and how mid- and late-career adults with work experience in various fields are poised to meet this demand.

Increasing Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the United States

The United States is a more ethnically and racially diverse nation today than it was in the past. According to the 2010 US census, the total population of the United States was 309 million, a 9.7% increase from 281 million in 2000. The population increase during the 2000s arose mainly from the so-called new minorities – Hispanic and Asian populations – which grew faster than any other major race or ethnic group (Frey, 2011a, 2011b; Humes et al., 2011). Constituting 16.3% of the total US population, Hispanics are now the largest minority group in the United States. The Asian population had the fastest rate of growth – 43.4% – of all ethnic and racial groups between 2000 and 2010.

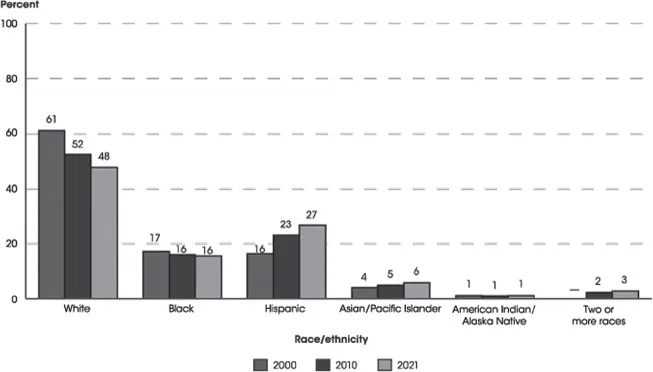

Population projections forecast that in the coming decades the United States will become a ‘plurality nation’, where the white population remains the largest single group, but no group is in the majority (US Census Bureau, 2012a). Much of this is fueled by higher birth rates among non-white groups. Although the census projections predict that the country will become a ‘majority-minority’ nation in 2042, the shift will come much earlier for younger age groups – 2018 for children under age 18 (Frey, 2012a). Already, non-white babies comprise more than half of all births in the United States; as of July 1, 2011, 50.4% of the nation’s population under age 1 was non-white (US Census Bureau, 2012b). School systems across the United States are at the forefront of demographic change as the school-age population (ages 5–17) is expected to become majority-minority in 2020 (Frey, 2012a). Figure 1.1 shows that white students’ share of pre-K through 12th grade enrollment decreased from 61% to 52% between 2000 and 2010 and is projected to drop further, to 48%, by 2021. In contrast, the percentage of Hispanic students increased from 16% to 23% between 2000 and 2010 and is projected to reach 27% by 2021.

Figure 1.1 Percentage distribution of US public school students enrolled in prekindergarten through 12th grade, by race/ethnicity: Selected years, fall 2000–fall 2021 (Source: US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Projections of Education Statistics to 2021; Common Core of Data (CCD), ‘State Nonfiscal Survey of Public Elementary and Secondary Education’, selected years, 2000–2001 through 2010–2011)

Figure 1.2 The United States as the #1 destination for immigrants in the world (Reproduced by permission of Pew Research Center)

In addition to higher birth rates among non-white populations, immigration is contributing to increased racial and ethnic diversity. In 2011, a record 40.4 million foreign-born persons lived in the United States, an increase of 9.3 million since 2000 (Pew Hispanic Center, 2013). Figure 1.2 shows that the United States is the most popular destination in the world for immigrants (Pew Hispanic Center, 2013). However, international migration is also a global phenomenon that contributes to population diversity in most West European countries and other English-speaking countries such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand (Coleman, 2015). Many countries in the developed world have low birth rates, whose effects are partly offset by the addition of immigrants from abroad.

America’s Aging Population

The other major demographic change that is taking place in the United States has to do with a rapidly aging population. Over the coming decades, people age 65 and over will make up an increasingly larger share of the US population. The 65+ population is expected to more than double between 2012 and 2060, from 43 million to 92 million (US Census Bureau, 2012a). This means that while one in seven people in the United States today is 65 or over, the 65+ population will represent over one in five US residents by 2060.

Much of the aging of the US population can be attributed to the baby boom generation – the cohort of Americans born between 1946 and 1964. Numbering 77 million, baby boomers today represent a quarter of the total US population (Ewing, 2012). In contrast to an increasingly non-white population of young people in the United States, the baby boom generation is overwhelmingly white. Whites account for 82.2% of all baby boomers; the black population, at 11.6%, is the largest minority group within the baby boom generation (Hellmich, 2010).

The aging of the US population is fueled by increased life expectancy, and lower overall birth rates (National Research Council, 2012). Due to improved nutrition, sanitation and medicine, people are living longer than in the past. Average life expectancy at birth in the United States was only 47.3 years in 1900, but it had increased to 78.5 years by 2009 (Arias, 2014). At the same time, overall birth rates have been falling. American couples are having fewer children and having them later in life than previous generations. Whereas in 1957 – at the height of the post-World War II baby boom – the fertility rate was 3.7 births per woman, the average rate for 2006–2010 was less than the replacement level of 2.1 births per woman (National Research Council, 2012). Replacement level refers to the total fertility rate at which a population exactly replaces itself from one generation to the next, without migration. A natural outcome of fewer children being born and more adults living longer is an aging population.

Population aging is actually a global phenomenon. While there were 810 million people age 60 or over in the world in 2012, accounting for 11.5% of the total world population, the over-60 population is projected to reach 2 billion by 2050, or 22% of the global population (United Nations Population Fund, 2012). Population aging is progressing fastest in developing countries. Whereas two out of three people age 60 or over live in developing countries today, nearly four in five people age 60 or over will live in the developing world by 2050. Recent declines in fertility rates in developing countries such as India, Mexico, Brazil and China are contributing to population aging in these countries and signal slower population growth in the coming years (Jacobsen et al., 2011). While the country with the oldest population in the world today is Japan, where more than 30% of the population is age 60 or over, there will be 64 countries where older people make up more than 30% of their population by 2050 (United Nations Population Fund, 2012).

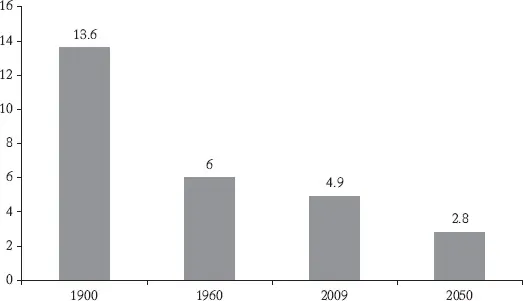

One of the reasons that the population of the United States is not aging as rapidly as other countries is the infusion of new immigrants. Because immigrants tend to be younger and have higher rates of labor force participation than native-born Americans, they lessen the impact of aging among the native-born population and workforce (Myers, 2007). However, current levels of immigration and birth rates are not enough to completely offset the effects of baby boomers’ retirement (Ewing, 2012). The over-65 population is projected to grow far more quickly than the working-age population over the coming decades, placing an enormous economic burden on taxpayers and workers. As can be seen in Figure 1.3, the elderly support ratio – the number of working-age adults (ages 18–64) per retiree (ages 65 or over) – decreased from 13.6 in 1900 to 6 in 1960, then to 4.9 in 2009; it is expected to drop further to 2.8 by 2050 (Jacobsen et al., 2011). This presents immense challenges to government programs such as Social Security1 and Medicare2, which help support older persons. In the coming decades, the United States will face an increasing need for new taxpayers to help fund these programs.

Figure 1.3 Number of working-age adults per retiree, 1900–2050 (Source: Jacobsen et al., 2011)

Government expenditures on Social Security and Medicare are projected to reach almost 15% of US gross domestic product (GDP) by 2050, which is up from 4% in 1970 (Ewing, 2012). In addition, driven by the rising cost of health-care services, as well as the sharp increase in the number of people receiving benefits, expenditures for Medicare are projected to exceed those for Social Security by 2030 (Jacobsen et al., 2011).

Researchers generally agree that increases in immigration will improve the financial status of Social Security and Medicare by a modest amount. Although immigration cannot fully compensate for the funding deficits of these government programs, it can make those shortfalls less severe (Van de Water, 2008). Because supporting the rapidly increasing number of retirees is expected to place immense strain on the budgets of federal and state governments, larger contributions will be required from a new corps of taxpayers, many of whom will be immigrants and their children (Myers, 2007). Today, the children of immigrants are the fastest growing demographic group within the US population. In 2009, nearly a quarter of all people age 17 and under in the United States had at least one immigrant parent (Tienda & Haskins, 2011). As these children come of age and join the workforce, the taxes they pay will help to sustain Social Security and Medicare for decades to come (Ewing, 2012).

However, the contributions that young people make to society are contingent on the opportunities that they receive, mainly through education (Frey, 2012b). Non-white youth in the United States face many barriers to academic and social success. They are more likely than white youth to attend segregated, underfunded schools with high student–teacher ratios, overcrowding and many students living in poverty (Fry, 2008). They are also much more likely than white youth to drop out of high school. Currently, high school dropout rates for Hispanics are more than twice as high as those of non-Hispanic whites (Aud et al., 2013). Failing to finish high school hurts not only the dropouts but also the overall economy. A single high school dropout costs the nation approximately $260,000 in lost earnings, taxes and productivity over the course of his or her lifetime (Amos, 2008). In addition, more than a third of Hispanic and black children live in poverty (Lopez & Velasco, 2011). Childhood poverty is linked with a range of negative adult socioeconomic outcomes, from poor school achievement and behavioral problems to lower earnings in the labor market (Tienda & Haskins, 2011).

Many analysts warn that if the United States does not improve academic performance among Hispanic and black children, the nation will have difficulty producing sufficient numbers of high-paying jobs to generate the tax revenue to maintain a robust retirement safety net (Brownstein, 2010). Helping young people advance into middle-class jobs through better educational opportunities is directly linked to the social and economic well-being of future retirees. It is a necessary investment in a society where the ratio of senior citizens to working-age adults continues to increase. Such investment requires strengthening early education, improving language education for young people and reducing financial and non-financial barriers to college (Tienda & Haskins, 2011). However, public spending greatly favors the older population over children; the US federal government currently spends $7 per elderly person for every $1 it spends per child (Isaacs, 2009). The rapid growth in public spending on retirement and health benefits for the elderly will place an increasingly heavy tax burden on today’s children, who will grow up to be working-age adults in the coming decades.

Generational Gap between the Gray and the Brown

Some observers point out that a significant generational gap is emerging between a heavily non-white population of young people and an overwhelmingly white population of older people in the United States (Frey, 2012b). In a National Journal cover story, Ronald Brownstein (2010) discusses the contrast in attitudes and desires between the mostly white older generation and the increasingly non-white younger population, or, what he calls ‘the gray’ and ‘the brown’. He argues that the two groups are ‘on a collision course that could rattle American politics for decades’. Comparing these two groups to tectonic plates, he notes that the two ‘slow-moving, but irreversible forces may generate enormous turbulence as they grind against each other in the years ahead’. Specifically, Brownstein refers to a growing tension between an older population that is increasingly resistant to taxes and public spending, and a younger population that views government education, health and social welfare programs as their avenues to upward mobility.

Significant racial differences by age exist in many parts of the United States, especially in states with growing Hispanic populations such as Arizona, Nevada, California, Texas, New Mexico and Florida (Frey, 2011a). Whereas whites compose a majority of the senior population in every state except Hawaii, non-whites compose a majority of the youth population in seven states and at least one-third of young people in 17 more (Brownstein, 2010). The largest race–age gap is found in Arizona, where less than 40% of the state’s children are white, compared with more than 80% of its seniors (Frey et al., 2011).

There are clear generational gaps in Americans’ attitudes toward immigration. While older people are more likely to voice a negative opinion about immigrants, young people are more likely to emphasize the benefits of new immigrants for American society (Cave, 2010). A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center found that only 23% of baby boomers regard the country’s growing population of immigrants as a change for the better, whereas 43% saw it as a change for the worse (Pew Research Center, 2011). Almost half of the baby boomers surveyed thought that the growing number of newcomers from other countries represented a threat to traditional US customs and values. In contrast, the survey found that young people were much more favorably disposed toward newcomers. Only 27% of the millennial generation (defined in this study as people born between 1981 and 1993) felt that newcomers threaten traditional American customs and values; more than two-thirds of the millennials believed that immigrants strengthen American society.

The Pew Research Center survey also found that there are deep generational divides in Americans’ opinions about government. More baby boomers (54%) prefer a smaller government that provides fewer social services than a bigger government that provides more services (35%), while millennials prefer a bigger government (56%) over a smaller government (35%). That baby boomers tend to favor a smaller government with fewer services is intriguing, given that they grew up benefiting from a wide range of government programs. Baby boomers were born to parents whose upward mobility was boosted by far-reaching public programs such as the GI Bill, which provides educational assistance to servicemen, veterans and their dependents (Frey, 2012b). In fact, baby boomers were more supportive of big government in their twenties and thirties (Pew Research Center, 2011). In recent years, however, more baby boomers have come to call themselves conservatives and have become critical of government performance. About three-quarters of baby boomers say that when something is run by the government, it is usually ineff...