![]()

Chapter 1

Background Information and Theory

In accordance with the profile of this book, this chapter cannot offer a comprehensive review of the theory and research associated with the complex issues addressed. Instead, we first provide some background information about the research site, Hungary, and then introduce certain key theoretical constructs to help to contextualise the topics addressed later. For a more detailed account of the particular topics, please refer to the works cited in the text.

A Thumbnail Description of Hungary

Hungary is a relatively small country in Central Europe with a population of around 10 million (for a map, see Figure 1.1). Situated largely in the Danube Valley and surrounded by the Carpathian Mountains, the greatest internal distance within the country does not exceed 320 miles. Hungary has had a rather turbulent history. Founded by the Magyar tribes migrating from the East in the 10th century, the country soon adopted Christianity and became a thriving feudalist kingdom, reaching its peak in the 15th century. Hungarians like to remember this ‘Golden Age’ when, for a brief period, the illusion of grandeur was within arm’s reach and the Hungarian army achieved success after success – something that is so difficult for us to imagine because Hungarian forces have not won a single major battle or war since then. After these glorious days Hungary became a buffer state between the expanding Ottoman and Hapsburg Empires (the Danube Valley offered an ideal battle ground) and in 1526 the country was conquered by the Turks. They were expelled by the Hapsburgs after 150 years but this ‘liberation’ did not lead to freedom but rather to a 400-year Hapsburg domination with regular and consistently unsuccessful Hungarian uprisings.

Being on the losing side in World War I meant that the territory of Hungary was reduced substantially, to about one-third of its original size. Partly to regain the lost land, Hungary allied with the Germans in World War II and when our allegiance became too reluctant in 1944, German forces occupied the country. Hungarians experienced another curious ‘liberation’ in 1945 by the Russian Red Army, which lead to further occupation of the country and to yet another failed uprising in 1956. Then in 1989, completely out of the blue as far as Hungarians were concerned, the Soviet Union collapsed and to our great surprise we found ourselves free! This was the beginning of a whole new chapter in Hungarian history, and nothing illustrates better the dramatic changes than the fact that the first president of the country, Árpád Göncz, had been formerly sentenced to life imprisonment by the previous Communist regime for his role in the 1956 revolution; interestingly he learned English so well in prison that he later translated Tolkien’s ‘Hobbit’ and part of ‘The Lord of the Rings’ trilogy into Hungarian. The last Russian soldiers withdrew from Hungary in 1991 and the country joined the NATO at the end of the decade and the European Union in 2004.

Figure 1.1 Map of Hungary within Europe

Hungary’s location on the latent geopolitical/cultural border separating Eastern and Western Europe is rather special: this borderline has been in evidence for the past two thousand years, with the Roman Empire having its eastern border, the Turkish Empire its western border, the Hapsburg Empire its eastern border, and recently the Soviet Union its western border (the ‘Iron Curtain’) in Hungary. In addition, the country also lies at the dividing line between Western and Eastern (Orthodox) Christianity, which reflects the country’s position being halfway between Rome and Byzantium (Istanbul), the two religious centres that determined Christian orientation in the Middle Ages. Hungary’s ‘halfway’ position is reflected in the strikingly different characteristics of the eastern and western parts of the country, separated by the River Danube. While the east of the country has more rural, traditional and relatively poor areas, the west of the country (adjacent to Austria) is more developed and westernised.

The capital of Hungary, Budapest, is situated along the Danube in the centre of the country. It is a modern metropolis, forming a ‘state within the state’ with a quarter of the total Hungarian population living there. It is the most developed area in the country and constitutes the undisputed economic centre, which is augmented by the fact that none of the other Hungarian cities have more than 10% of Budapest’s population. Budapest is also the primary tourist destination in Hungary because it is both a lively regional cultural centre and an attractive city, with the waterfront of the River Danube dividing the city into Buda and Pest being part of the UNESCO World Heritage (an exclusive list of fewer than 800 cultural and beauty spots in the world).

Language learning situation

As Hungary is almost exclusively populated by Hungarians, the country is one of the rather rare examples of a national context in which there are no significant ethnolinguistic minorities: According to the 2000 census, 92.3% of the population claimed to be ethnic Hungarian and the proportion of people with Hungarian as their mother tongue was even higher, 98.2% (Central Statistical Office, 2004a). Accordingly, people do not speak languages other than Hungarian unless they learn them at school. From 1949 to 1989, for obvious political reasons, Russian was taught as the first foreign language at all levels of the school system; as a result, by the time of graduation from university, one had studied Russian for a minimum of 10 years. However, the learning of Russian in Hungary was a perfect illustration of Gardner’s (2001) claim that language learning without sufficiently positive language attitudes to support it is a futile attempt: Hungarians were very reluctant to learn Russian because it represented the oppressive power, and, consequently, in the years of 1979–1982, not more than 2.9% of the Hungarian adult population spoke Russian, which number decreased by 1994 by almost 1% (Terestyéni, 1996).

From the 1970s onwards, certain modern Western languages, primarily English and German, started to reappear in the national curriculum, although in a rather limited way. Their significance at the primary level remained minimal: for example, in the 1988/89 school year nearly 100% of primary pupils learnt only Russian. The picture was more positive at the secondary level: by the end of the 1980s, more than half of the secondary school students were offered a second foreign language besides Russian (Enyedi & Medgyes, 1998).

Due to the sweeping changes taking place in the country, the reform of state education began in earnest at the very end of the 1980s and one of the first and most important steps in this modernisation process was the abolition of the compulsory status of Russian in the national curriculum. The gap was filled with a variety of western languages, primarily with English and German, for the schools to choose from, but due to the unavailability of enough trained English and German teachers the transition was gradual: as already mentioned in the Introduction, according to our data, in 1993 still over 50% of the final-year primary school population (i.e. the target age group of our study) learnt Russian; however, by the end of the 1990s Russian had completely disappeared from the primary school system, and the disappearance of Russian at secondary level was even quicker (Vágó, 2000).

Currently, as Fodor and Peluau (2003) summarise, the L2 proficiency level of Hungarians is rather poor. The overwhelming majority of Hungarians are monolingual; only about 10–12% of the population claim to be able to speak a foreign language and less than 5% can express themselves in two languages. The main languages learned are English and German with about 500,000 learners each; the third foreign language, French, is way behind these two frontrunners with only about 50,000 learners.

International integration

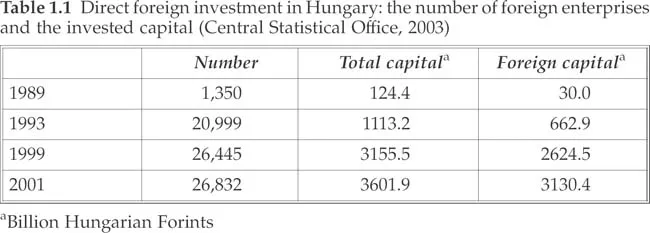

The new political setup of the country brought along a rapid increase of both direct and indirect contact with foreign businessmen and tourists, as well as with foreign cultural and commercial products. As can be seen in Table 1.1, over a period of 12 years (between 1989 and 2001) the number of foreign enterprises in Hungary multiplied 20 times, with the actual capital being invested multiplying over 100 times! A similar tendency can be observed in the total amount of foreign trade as over the same period there was a 19–20 time growth (see Table 1.2). These figures illustrate well the extent of the rapid integration of the country into the international economic network in the 1990s.

The significant financial and economic foreign influence was accompanied by a great deal of direct contact with tourists visiting Hungary. Table 1.3 presents statistics of the foreign visitors coming to Hungary over the examined period. Besides the total number of tourists, we also included in the table specific figures concerning the L2 communities that our survey focused on, but we restricted the list to western nations only because figures describing East European visitors are unreliable from our perspective as they also include members of the Hungarian minority in neighbouring countries visiting the motherland. As can be seen in the table, there was a significant (60%) increase of visitors between 1989 and 1993, after which the number has subsided and although recently there have been signs of the recovery of the tourist industry, the number of visitors is still behind the 1993 level. The statistics show clearly that German-speaking tourists make up by far the greatest portion of the total number of western tourists, with any other nationalities (and even the combined US/UK group) amounting only to less than 10% of this figure. Thus, there is a dominance of German-speaking visitors, which is well reflected by the fact that in the Hungarian tourist industry the primary foreign language is German.

Table 1.2 Total amount of Hungarian foreign trade (Central Statistical Office, 2004b)

| Year | Importa | Exporta |

| 1989 | 523,507 | 517,323 |

| 1993 | 1,162,491 | 819,915 |

| 1999 | 6,645,562 | 5,938,525 |

| 2001 | 10,695,408 | 9,643,710 |

Language Globalisation

Globalisation refers to the ‘way in which, under contemporary conditions especially, relations of power and communication are stretched across the globe, involving compressions of time and space and a recomposition of social relationships’ (Mohammadi, 1997: 1). In an article analysing the psychology of globalisation, Arnett (2002) points out that in the broad sense globalisation has existed for many centuries as a process by which cultures influence one another and become more alike through trade, immigration and the exchange of information and ideas. The reason why the current phenomenon is different from this ongoing process is, he argues, that in recent decades the degree and intensity of the interplay of different cultures and world regions have accelerated dramatically because of advances in telecommunications and a rapid increase in economic and financial interdependence worldwide. This is well reflected by the fact that, according to figures cited by Arnett, international travel has increased by 700% since 1960. In conclusion, he states:

In many cultures today, people who are middle-aged or older can remember a time when their culture was firmly grounded in enduring traditions, barely touched by anything global, Western, or American. However, few young people growing up today will have such memories in the decades to come. Young people in every part of the world are affected by globalisation; nearly all of them are aware, although to varying degrees, of a global culture that exists beyond their local culture. Those who are growing up in traditional cultures know that the future that awaits them is certain to be very different from the life their grandparents knew. (Arnett, 2002: 781)

Although globalisation is strongly linked to economic factors such as the increasingly global reach of multinational corporations and the growing inter-relatedness of local economies, it also has a significant linguistic dimension. Due to their geopolitical significance, certain languages appear to be gaining relative influence, often at the expense of other languages, resulting in a new linguistic hierarchy. As Maurais and Morris (2003a: 9) point out, ‘Language shift is not new, but the contemporary global scope of linguistic competition is’. Thus, in today’s world we can see winners and losers on a scale never experienced before, and this phenomenon has accelerated recently.

Because of its prominent linguistic relevance, the impact of globalisation has been the subject of a great deal of research in applied linguistics in the past and the importance of the topic is also reflected by the fact that several journals are specifically dedicated to it, for example English Today and World Englishes. The titles of these two journals also indicate that the key issue in the language globalisation literature concerns the spread of English, with scholars taking two broad stances: they subscribe either to the Diffusion of English paradigm or the Ecology of Language paradigm, depending on whether they see the present rate of spread of English as a second/foreign language as a blessing or a threat (Phillipson & Skutnabb-Kangas, 1997). The first paradigm involves a ‘free-market’ view of the natural selection/survival of the fittest (and especially ‘Global English’, as Graddol (1997), called it), whereas ecological theorists represent a ‘green’ view stating that diminished language diversity is a tragedy and an irrevocable loss.

It is easy to see why the seemingly unstoppable spread of English has generated strong emotional overtones to the topic. Some scholars have gone as far as speaking about a ‘linguistic genocide’ (Skutnabb-Kangas, 2001) and this view has been expressed – although perhaps less starkly – by a number of leading researchers during the past decade (e.g. Crystal, 1997; Fishman, 1992; Graddol & Meinhof, 1999; Kachru, 1992; Pennycook, 1994; Phillipson, 1992). However, some other theoreticians have taken a more cautious approach; for example, Tonkin (2003) emphasised that because technology is making the world smaller and the population growth is making it more crowded, we must acknowledge the indisputable need for direct communication and thus for a lingua franca, which for the foreseeable future is likely to be English. Indeed, many if not most scholars would agree that there is a certain need for a global language, but at the same time most would also emphasise that there are certain dangers of having a single global medium of communication. The main task, then, is not so much to try and fight this process as to develop ways of preventing English from encroaching on the domains of other languages by balancing its spread with the maintenance of linguistic diversity (Maurais & Morris, 2003a; Tonkin, 2003).

In any case, language globalisation has become part of the linguistic landscape and most scholars reflecting on the future fate of English seem to have arrived at the conclusion that rather than diminishing, the position of English as a global language is becoming stronger (Crystal, 1997). We can only speculate about the future of other traditionally prominent languages such as French and German, let alone languages of smaller speech communities, but the prospects are not bright. A study by Truchot (1997: 76), for example, found that the use of English is spreading even within France, concluding that ‘languages which were protected by borders are now challenged on their own territory as their users are faced with demands of world communication’. It is also uncertain as to whether there will be any new challenges to English in the near future by Chinese, Hindi, Spanish or Arabic, reflecting emerging new power centres in the world, as it seems increasingly clear that for various reasons none of them can offer a viable alternative at present.

From a European perspective it is particularly noteworthy that scholars have started to speak about a special variety of English, ‘Euro-English’, referring to an educated European English variety used by Continental European business people and other professional administrators to communicate together (Strevens, 1992). The status of Euro-English is often debated because, as McArthur (2003: 57) points out, the term has often been used to mean ‘bad English perpetrated in Brussels’, associated with an ‘even more hybridised and dubious phenomenon known as Eurospeak’. Others, however, see it as an emerging variety, which will eventually serve as a European lingua franca. Projects have been, and are being, carried out in order to describe Euro-English in a systematic way; see, for example, the work on the phonology of the Euro-English accent (Jenkins, 2000, 2001); English as a lingua franca in the A...