eBook - ePub

Continua of Biliteracy

An Ecological Framework for Educational Policy, Research, and Practice in Multilingual Settings

This is a test

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Continua of Biliteracy

An Ecological Framework for Educational Policy, Research, and Practice in Multilingual Settings

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Biliteracy - the use of two or more languages in and around writing- is an inescapable feature of lives and schools worldwide, yet one which most educational policy and practice continue blithely to ignore. The continua of biliteracy featured in the present volume offers a comprehensive yet flexible model to guide educators, researchers, and policy-makers in designing, carrying out, and evaluating educational programs for the development of bilingual and multilingual learners, each program adapted to its own specific context, media, and contents.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Continua of Biliteracy by Nancy H. Hornberger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Continua of Biliteracy*

As public schools in the United States increasingly serve speakers of languages other than English in a predominantly English-speaking society, the need for an understanding of biliteracy becomes more pressing. Among the 18 research priorities recently established by the US Department of Education, the first listed is ‘the teaching and learning of reading, writing, or language skills particularly by non- or limited English speaking students’ (Department of Education, 1988).

It is not that such teaching and learning does not occur. Consider the following three narrative vignettes. In an urban fourth-grade class composed of 11 Asian and 17 Black children, Sokhom,1 age 10, has recently been promoted to the on-grade-level reading group and is doing well. She is no longer in the school’s pull-out English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) program and spends her whole day in the mainstream classroom. At home, she pulls out a well worn English–Khmer dictionary that she says her father bought at great expense in the refugee camp in the Philippines. She recounts that, when she first came to the United States and was in second grade, she used to look up English words there and ask her father or her brother to read the Cambodian word to her; then she would know what the English word was. Today, in addition to her intense motivation to know English (‘I like to talk in English, I like to read in English, and I like to write in English’), Sokhom wants to learn to read and write in Khmer, and in fact has taught herself a little via English.

In another urban public school across the city, Maria, a fifth grader who has been in a two-way maintenance bilingual education program since prekindergarten, has both Spanish and English reading every morning for one and a quarter hours each, with Ms Torres and Mrs Dittmar, respectively. Today, Mrs Dittmar is reviewing the vocabulary for the story the students are reading about Charles Drew, a Black American doctor. She explains that ‘influenza’ is what Charles’s little sister died of; Maria comments that ‘you say it [influenza] in Spanish the same way you write it [in English].’

In the same Puerto Rican community, in a new bilingual middle school a few blocks away, Elizabeth, a graduate of the two-way maintenance bilingual program mentioned above, hears a Career Day speaker from the community tell her that, of two people applying for a job, one bilingual and one not, the bilingual has an advantage. Yet Elizabeth’s daily program of classes provides little opportunity for her to continue to develop literacy in Spanish; the bilingual program at this school is primarily transitional.

All three of these girls are part of the biliterate population of the United States. The educational programs they are experiencing are vastly different with respect to attention to literacy in their first language, ranging from total absence to benign neglect to active development; and from mainstream with pull-out ESOL to transitional bilingual education to two-way maintenance bilingual education. Biliteracy exists, as do educational programs serving biliterate populations. Yet, provocative questions remain to be answered, primarily about the degree to which literacy knowledge and skills in one language aid or impede the learning of literacy knowledge and skills in the other.

A framework for understanding biliteracy is needed in which to situate research and teaching; this review attempts to address that need. Because biliteracy itself represents a conjunction of literacy and bilingualism, the logical place to begin to look is in those two fields. This seems particularly appropriate because the twin, and some suggest conflicting (Fillmore & Valadez, 1986: 653), goals of bilingual education and ESOL programs in elementary public schools in the United States are for students to (a) learn the second language (English) and (b) keep up with their monolingual peers in academic content areas.

The fields of literacy and bilingualism each represent vast amounts of literature. There is a relatively small but increasing proportion of explicit attention to (a) bilingualism within the literature on literacy and literacy within the literature on bilingualism and (b) second or foreign languages within the literatures on the teaching of reading and writing and reading and writing within the literatures on second or foreign language teaching. Perhaps the reason for the relative lack of attention is that, when one seeks to attend to both, already complex issues seem to become further muddled. For example, Alderson (1984: 24) explored one such muddled area: If a student is having difficulty reading a text in a foreign language, should this be construed as a reading problem or a language problem? It turns out, however, as this review will show, that by focusing findings from the two fields on the common area of biliteracy, we elucidate not only biliteracy itself but also literacy and bilingualism. All the above literatures were considered for this review, with special focus on those studies and papers that explore the area of overlap, that is, biliteracy.

Neither a complete theory of literacy nor a complete theory of bilingualism yet exist. In both fields, the complexity of the subject; the multidisciplinary nature of the inquiry, including educators, linguists, psychologists, anthropologists, sociologists, and historians; and the interdependence between research, policy, and practice make unity and coherence elusive objectives (see Hakuta, 1986: x; Langer, 1988: 43; Scribner, 1987: 19).

This review proposes a framework for understanding biliteracy, using the notion of continuum to provide the overarching conceptual scheme for describing biliterate contexts, development, and media. Although we often characterize dimensions of bilingualism and literacy in terms of polar opposites, such as first versus second languages (L1 vs L2), monolingual versus bilingual individuals, or oral versus literate societies, it has become increasingly clear that in each case those opposites represent only theoretical endpoints on what is in reality a continuum of features (see Kelly, 1969: 5). Furthermore, when we consider biliteracy in its turn, it becomes clear that these continua are interrelated dimensions of one highly complex whole.

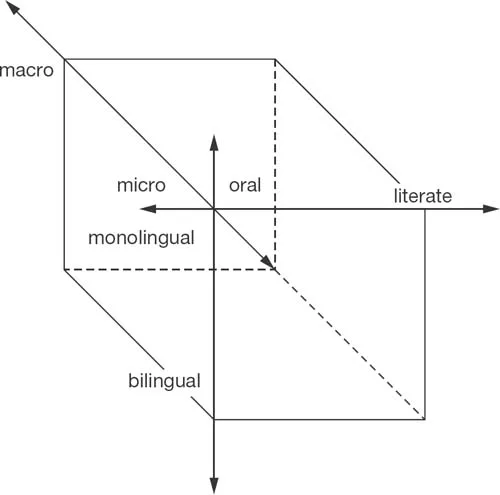

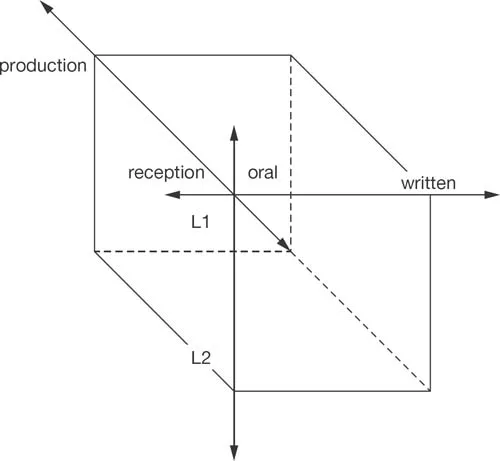

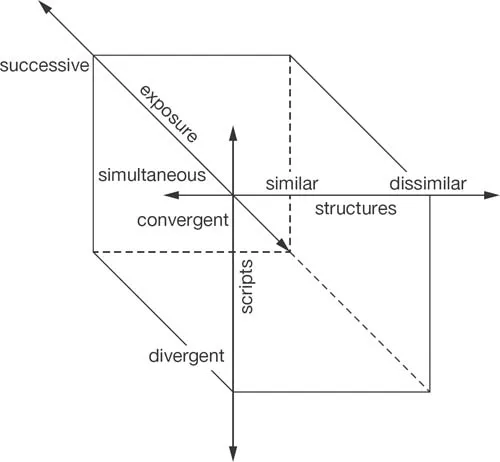

Figures 1.1–1.3 schematically represent the framework by depicting both the continua and their interrelatedness. The figures show the nine continua characterizing contexts for biliteracy, the development of individual biliteracy, and the media of biliteracy, respectively. Not only is the three-dimensionality of any one figure representative of the interrelatedness of its constituent continua, but it should be emphasized that the interrelationships extend across the contexts, development, and media of biliteracy as well (see Figures 1.1–1.3).

The notion of continuum is intended to convey that, although one can identify (and name) points on the continuum, those points are not finite, static, or discrete. There are infinitely many points on the continuum; any single point is inevitably and inextricably related to all other points; and all the points have more in common than not with each other. The argument here is that, for an understanding of biliteracy, it is equally elucidating to focus on the common features and on the distinguishing features along any one continuum.

In an attempt to disentangle the complexities of biliteracy, the sections that follow introduce the nine continua one at a time, citing illustrative works from the literatures mentioned above in support of each one. In the first section, represented in Figure 1.1, contexts for biliteracy are defined in terms of three continua: micro–macro, oral–literate, and monolingual–bilingual. The second section, represented in Figure 1.2, introduces the continua that characterize the development of the biliterate individual’s communicative repertoire: reception–production, oral language–written language, and L1–L2 transfer. The third section, represented in Figure 1.3, describes three continua characterizing the relationships among the media through which the biliterate individual communicates: simultaneous–successive exposure, similar–dissimilar structures, and convergent–divergent scripts. Throughout the discussion of the nine continua, the interrelationships among them are also brought out. The paper concludes with comments on the implications of the continua for research in and teaching of biliteracy.

Figure 1.1 The continua of biliterate contexts

Figure 1.2 The continua of biliterate development in the individual

Figure 1.3 The continua of biliterate media

Contexts of Biliteracy

An interest in context as an important factor in all aspects of language use dates back at least to the early 1960s and the beginnings of sociolinguistics and the ethnography of communication (Fishman, 1968; Hymes, 1964; Pride & Holmes, 1972). Building from communicative theory and work by Roman Jakobson published in 1953 and 1960, Hymes suggested an array of components that might serve as a heuristic for the ethnographic study of speech events, or more generally, communicative events, where such events refer to activities or aspects of activities that are directly governed by rules or norms for the use of language and that consist of one or more speech acts.2 This array of components included participants, settings, topics, goals, norms, forms, genres, and so forth and was later formulated by Hymes (1974: 53–62) into the mnemonic SPEAKING (Setting, Participants, Ends, Act, Key, Instrumentalities, Norms, Genres).

From within the ethnography of communication have come occasional calls for the ethnography of writing (Basso, 1974) and the ethnography of literacy (Szwed, 1981). In a recent paper Dubin (1989) assured those attending the Communicative Competence Revisited Seminar that the ethnography of communication is alive and well in the literacy field, and she went on to describe her own current study of what she termed the ‘mini-literacies’ of three biliterate immigrants.

Indeed, in the last decade the literacy field has seen a series of persuasive arguments for the significance of context for understanding literacy. Heath is one who has explicitly undertaken the study of literacy in context, within an ethnography of communication framework. She noted that reading varies in its functions and uses across history, cultures, and ‘contexts of use as defined by particular communities’ (1980: 126) and went on to document this in her 1983 study. Scribner and Cole (1981) drew from their study of literacy in Liberia to argue that ‘literacy is not simply learning how to read and write a particular script but applying this knowledge for specific purposes in specific contexts of use’ (236). Gee (1986) contended that literacy has no meaning ‘apart from particular cultural contexts in which it is used’ (734). Also, Langer (1988) found one of three new emphases of books and articles on literacy in the 1980s to be ‘the effects of context and culture on literacy,’ and went on to suggest that all three literacy volumes she reviewed (Bloome, 1987; de Castell et al., 1986; Olson et al., 1985) share a concern with literacy in context (or what Olson et al. called literacy as situational).

Street (1984) rejected what he labeled the autonomous model of literacy and argued for the ideological model, which assumes that the ‘meaning of literacy depends upon the social institutions in which it is embedded’ (8). Therefore, he continued, it makes more sense to refer to multiple literacies than to any single literacy; he described such a case from his own fieldwork in Iran (see also Gee, 1986: 719). Thus, he opted for a contextualized rather than a decontextualized view of literacy.

Biliteracy, like all literacies, can be taken to be ‘radically constituted by [its] context of use’ (Erickson, 1984: 529). What do the literatures on bilingualism, literacy, and biliteracy tell us about the contexts of biliteracy? This review suggests that there is an implicit, and at times explicit, understanding in the literatures that any particular context of biliteracy is defined by the intersection of at least three continua – the micro–macro continuum, the oral–literate continuum, and the monolingual–bilingual continuum – and that any attempt to understand an instance of biliteracy by attending to only one of these contextual continua produces at best an incomplete result.

The micro–macro continuum

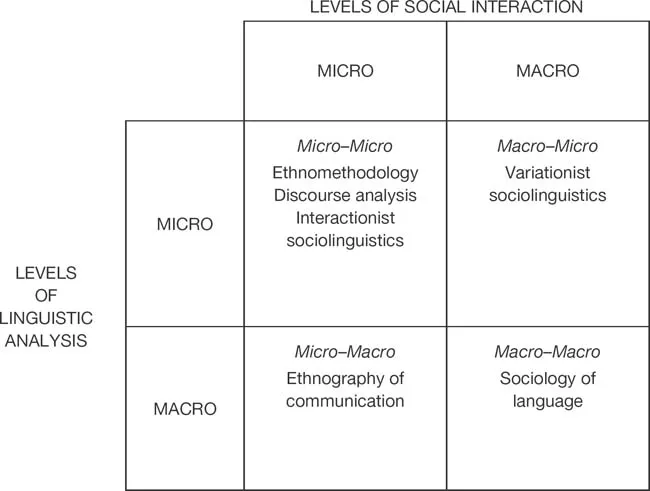

Sociolinguists have recognized a distinction between micro and macro levels of analysis from the beginning. Indeed, one can characterize areas of sociolinguistic inquiry in a quadrant model that distinguishes between micro and macro levels of analysis of social interaction and micro and macro levels of linguistic analysis (see Figure 1.4). Such a model makes clear the range of contexts for the analysis of language use. Thus, generalizing broadly, at the micro–micro level of context a particular feature of language (e.g. cohesion, rhythm, or a phoneme) is examined in a particular piece of text or discourse; at the micro–macro level, patterns of language use are examined in the context of a situation or a speech event; at the macro–micro level, a particular feature of language is examined in the context of a society or a large social unit; and at the macro–macro level of context, patterns of language use are examined within or across societies or nations.

Figure 1.4 Micro and macro sociolinguistics

Insights from a consideration of bilingualism in context include, for example, at the micro–macro level, the recognition that the bilingual individual keys language choice to characteristics of the situation (e.g. Grosjean, 1982: 127–145). At the macro-macro level are the insights that there may exist domains3 associated with one or another language in bilingual societies (e.g. Fishman, 1986 [1972]; Grosjean, 1982: 130–2), or that a language may fulfill one of a range of functions in the society. These functional roles include the high or low variety in a diglossic situation,4 such as classical and colloquial Arabic in Arabic-speaking societies (Ferguson, 1959); a second language of widespread use, such as English in Singapore (Williams, 1987); a foreign language (e.g. Alderson & Urquhart, 1984); or a language of wider communication (LWC), such as Swahili in East Africa.

On the other hand, insights from a consideration of literacy in context include, for e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Part 1: Continua of Biliteracy

- Part 2: Language Planning

- Part 3: Learners’ Identities

- Part 4: Empowering Teachers

- Part 5: Sites and Worlds

- Part 6: Conclusion

- Afterword

- Index