![]()

1The Drivers of Demand for Language Services in Health Care

Allison Squires

Societies with a rich diversity of skills and experiences are better placed to stimulate growth through their human resources, and migration is one of the ways in which the exchange of talent, services, and skills can be fostered. Yet migration remains highly politicized and often negatively perceived, despite the obvious need for diversification in today’s rapidly evolving societies and economies.

(Appave & Laczko, 2011: 15)

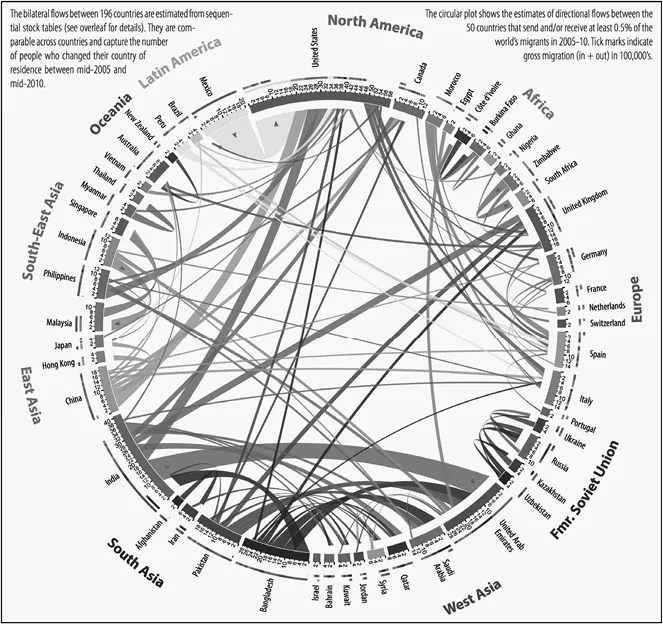

Figure 1.1 illustrates the current complexity of global migration. Geographically, individuals tend to migrate first within their country, usually from rural to urban areas. Reasons for domestic migration may include changes in local conditions that force migration owing to economic (job seeking or employment changes), political (conflict or war), educational (degree or training seeking) or ecological reasons. If international migration occurs, this may happen first within the local region (e.g. South Asia) and then internationally. The most common pattern is from a low or middle income country to a high income country. Additionally, an individual’s education level will often dictate how migration occurs, whether it is voluntary and driven by a confirmed opportunity, voluntary and driven by potential opportunity, or involuntary driven by a variety of reasons.

Figure 1.1 Global migration flows 2005–10 Adapted from http://www.global-migration.info/VID_Global_Migration_Datasheet_web.pdf Team at the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA,VID/ÖAW,WU): Nikola Sander, Guy J. Abel and Ramon Bauer. Circular plots created with Circos (Krzywinski, M. et al. Circos: an Information Aesthetic for Comparative Genomics. Genome Res, 2009, 19:1639–1645).

More than ever before, individuals migrate to other countries primarily for work opportunities when career advancement opportunities arise, their local economies do not produce enough opportunities for paid employment or when underemployment prevails. War and conflict zones may also drive workers from their country temporarily or permanently and transferring the skills of these migrants can prove challenging (The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development 2011; Appave & Laczko, 2011; Docquier et al., 2009). Nonetheless, migration for work often benefits many workers as they develop new technical, social and linguistic skills that may make them more competitive in their originating country labor markets and act as buffers against economic shocks (Durand & Massey, 2010; Siqueira et al., 2013; Walani, 2013; Shihadeh & Barranco, 2010; Bartram, 2010; Hagan et al., 2011; Tilly, 2011; Docquier et al., 2009). Migrating workers are also major contributors to the global economy through remittances: earnings sent back to the home country to the migrant’s family often to pay for housing and healthcare costs (Carling, 2009). In 2014, the World Bank estimated that remittances sent home by migrating workers contributed US$400 billion to the global economy and would increase by 7–9% annually through 2020 (The World Bank, 2016). With international travel easier than at any other point in history, the 21st-century worker has a high probability of migrating permanently or temporarily for work at some point in their lifetime.

Yet as a global phenomenon, 21st century global migration patterns are changing health services delivery in countries around the world. For some healthcare systems, this presents new demands on service delivery while others see increased challenges on already stretched ones. Changing countries is stressful in good and bad ways and often impacts individual and family health. Legacies of origin country health system strengths and deficiencies will travel with the migrant in terms of their health profile. Whether they are an investment banker who has moved from New York to London or an internationally educated nurse from the Philippines who moves to the Middle East to staff healthcare systems or a Central American migrant fleeing stagnant economies and drug violence, newly arrived migrant workers undergo a transition period, often known as culture shock. The stress of the transition often affects their mental health as some individuals adapt more readily than others to new cultures, contexts and stressors while others may develop depression, anxiety and other mental health sequelae that affect their physical health, all as a direct result of their migration experiences and sudden absence of traditional support systems (Rudmin, 2010; Bauer et al., 2010; Riggs et al., 2012; Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012; Teruya & Bazargan-Hejazi, 2013; Lassetter & Callister, 2008). Even though the cumulative causation of migration may increase social networks and support systems abroad (Fussell, 2010; Sanderson & Kentor, 2008) that may lessen the effects of migration experiences on health, the phenomenon’s effects on health are complex.

Consequently, migrants may or may not access the healthcare system in their destination country when needed. Several factors influence these behaviors. First, insurance schemes play a large role in whether or not the migrant accesses the local healthcare system simply owing to whether or not they can get coverage in their new country. Even countries with universal health coverage do not necessarily provide coverage to new immigrants (Biswas et al., 2011; Docquier et al., 2009; Reyes & Hardy, 2015; Siddiqi et al., 2013). The second major factor is a language barrier. Even if a migrant comes from a country, for example, where English is an or the official language and has migrated to another English-speaking country, the language of healthcare systems and illness descriptors can be different enough to affect how and when the migrant accesses the healthcare system (Squires et al., 2013). When the migrant has little to no language skill in the official language(s) of a country, it becomes a major barrier to accessing and utilizing healthcare services. Even countries with long histories of receiving immigrants can be unprepared for the reality of individuals who cannot communicate effectively with a healthcare provider.

Migrant Identity and Health

Regardless of the reason for migration, researchers categorize migrants as documented, undocumented and refugee. The latter two situations have the greatest likelihood of affecting the health of individuals and their families because of the nature of the migration experience. Documented individuals who migrate generally have no greater risk for health issues when living and working in high-income countries than in their home country. Health risks associated with living and working in a low- or middle-income country are related to the disease burden inherent to the country and the ability of the local health system to respond to their needs or transfer the individual to another country for treatment.

Undocumented individuals migrate to a country without legal citizenship or work papers. Many may arrive in the country via a tourist visa and remain after it expires. Others arrive through human traffickers and may have been subject to emotional, physical or sexual abuse during the process. Nonetheless, once they arrive they contribute economically to countries by providing inexpensive labor, primarily in the service, agricultural and construction sectors. Health issues in this population can result from the migration experience, the success or failure of their integration into the new community or occupationally related injuries which may or may not receive timely treatment.

Refugees have fled their home country for political reasons. The United Nations (UN) defines them as:

Any person who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside of the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to return [to it]. (Source: UN Convention Related to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol)

The skills of these individuals and their education levels vary widely. Translating their skills into equivalent positions in the receiving country is often a challenge. Proof of education documents may be lost or unobtainable and training curricula may be sufficiently different that they do not meet the competency or credentialing standards of the receiving country. This means this population is at risk for underemployment or may need to repeat their education. These individuals are also at high risk for post-traumatic stress disorder and may manifest these symptoms physically. Asylum seekers may face similar challenges.

Conclusion

Language often cannot be separated from migrant status, which also impacts health, so healthcare organizations must also be knowledgeable about the particular health risks that result from the migration experience. In consideration of the aforementioned factors, this chapter focuses on how migration dynamics influence demand for language services in healthcare systems and the subsequent implications for policy (both organizational and national) and research. It will examine how these experiences start to create demand for language services in healthcare systems and conclude with recommendations to better account for the demand...