![]() PART I – DIGITAL POETRY

PART I – DIGITAL POETRY![]()

THE INTERACTIVE DIAGRAM SENTENCE: HYPERTEXT AS A MEDIUM OF THOUGHT

Jim Rosenberg

1. Diagrams: A Separate Channel for Syntax

The most basic elemental structural act, the most fundamental micromaneuver at the heart of all abstraction, is juxtaposition, ‘structural zero’: the act of simply putting an element on top of another, with no other structural relation between the two elements except that they are brought together. But consider the problem of the poet in bringing this about. When a sound is played simultaneously with another sound, the result is a sound. When a painter places a bit of coloured space on top of another bit of coloured space, the result is a bit of coloured space. A mathematician would say that the domains of the composer or visual artist are closed with respect to the operation of juxtaposition: the result of juxtaposing two elements from the domain is another element from the domain. But what happens when we juxtapose words? Whether it is done by means of sound – either via simultaneous readings by multiple performers, or by overlaying magnetic or digital media – or visually, the result of juxtaposing words – in the almost palpable physical sense of putting them directly on top of one another – is likely to be sheer unintelligibility: one will be lucky to make out any of the words at all. How is the poet to achieve juxtaposition with no sacrifice of intelligibility?

But it gets worse: how can direct juxtapositions of words be used in larger structures? It is not hard to work in modes that give up such structures as syntax. One simply does without. Asyntactic poetry is a large and fruitful domain in which to work. On the other hand, giving up all possibility of structure is giving up a great deal indeed. Syntax is at the heart of how we normally structure words. How does one achieve such structuring and yet still have complete freedom to use juxtaposition wherever it is artistically important? How does one designate the structural role of a juxtaposition in a larger structure? One could put this question a bit more crudely by asking: What is the part of speech of a juxtaposition? The composer John Cage once criticized the twelve-tone system as having no zero.1 One could say that syntax ‘has no zero’: in a sentence every element has its structural role with respect to the syntax diagram, or parse tree; there is no way to have words in a sentence whose syntactical relationship to one another is the null relationship: no relation at all except that they are brought together. How can the poet have her cake and eat it too? I.e., how can one keep both syntactical null relationships and much more elaborate relationships, in which juxtapositions act as elements?

These are some of the formal problems that have motivated my work going back more than 30 years. A method for approaching the second problem – how to incorporate null structures as structural elements – became apparent long before I realized how juxtaposition could actually be implemented. By devising an explicit visual structural vocabulary – separating syntax out into its own channel, so to speak – structural roles could simply be directly indicated. The elements occupying those roles might be words or word clusters or other structural complexes. Thus began a long series of works called Diagram Poems.

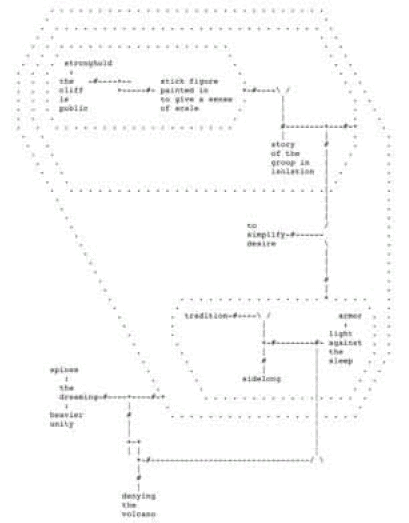

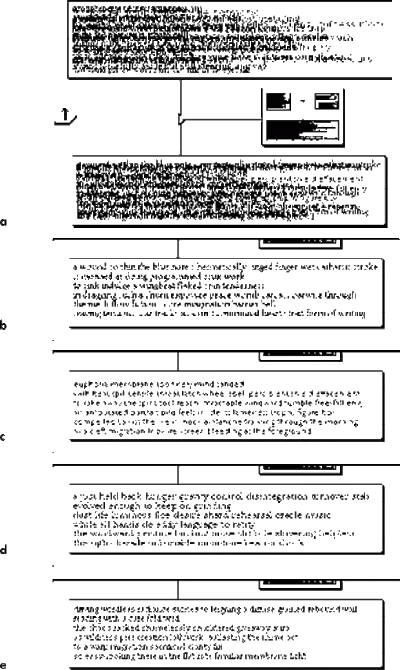

Figure 1: A diagram poem from Diagrams Series 3.

Figure 1 shows a poem from Diagrams Series 3.2 It illustrates many of the facilities provided by the diagram notation in a variety of works spanning a large number of years. The configuration:

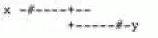

shows a simple modifier relationship where x is modified by y. The configurations:

show verb relationships; in the left case above, z acts as the verb relating x and y, in the right case above, y acts as the verb and x acts as the subject.

These relationships can be built up into complexes in two ways: where a ‘node’ in a relationship is a loop of dots, the element participating at that node is the entire contents of the loop; where a node terminates in the graphical part of a relationship, the element at that node is the act of making that relationship.

A number of interesting things happen when syntax is ‘externalized’ in this way. Syntax came about originally in conjunction with speech, where speaker and listener are constrained by: (1) the requirement that the listener ‘decode’ the message approximately synchronized in real time with the speaker; and (2) the aid of only whatever ‘temporary storage’ the listener has available in short-term memory. One might say that the function of syntax is to pre-code the message with storage cues so that the listener will know how to park pieces of the message in short-term memory so that they can be properly assembled in the logical relationships desired by the speaker – all in more or less real time without getting behind the speaker. Writing, however, changes the picture completely. Obviously, the real-time constraints are absent: the reader may take as much time as desired, may revisit parts of the message as many times as is necessary, and may even browse the message ‘out of order’. In addition, a written document may be said to provide its own storage. In contrast to speech, where whatever parts of the message that are not properly stored in short-term memory by the listener are simply (and irretrievably) gone, the written message persists: it stores itself, it stores its structure, it stores its own logical relationships.

Secondly, by externalizing syntax, all points and substructures in the message are accessible in ways not normally found in speech. That they are accessible to the reader has already been discussed. Some interesting ways they are accessible to the writer are revealed by Figure 1. Note the relationship of the phrase ‘story of the group in isolation’ to a larger whole in which it appears. In an externalized graphical syntax, such a relationship is easy to simply draw; joining a part with a larger whole in which it participates is as easy as joining a part with a disjoint part. Relationships between a part and a larger whole in which the part occurs are an obvious logical structure that occurs commonly in the world; yet this is difficult to do in conventional syntax. In addition, the fact that relationships may simply be drawn to parts of the message already laid out allows for complex multiple pathways to be established within even small messages; the message may feed back upon itself. Feedback, while a ubiquitous structure in nature, is notoriously difficult to deal with. It violates the principle set theorists call ‘well-foundedness’; it may induce the potential for infinite loops in computer programs; where feedback is introduced into the way sound elements are combined in an electronic synthesizer the results may be completely unpredictable: all bets are off. Figure 1 also illustrates this concept of feedback inside the sentence: the ‘highest-level’ logical relationship shown in Figure 1 relates the configuration at the very bottom, in which ‘denying the volcano’ is a modifier, with a cluster ‘already’ deep within the message: ‘armor: light against the sleep’.

A feedback loop may seem an inimical structure to a programmer, where the threat of infinite loop is ever present (and indeed the infinite loop stands out as an archetype ‘cardinal bug’ second only in its fearsomeness to an out-and-out crash); one may say that the threat of infinite loop stands as the fear at the heart of all programming. (Technically, the theorem that one cannot algorithmically determine whether a general computer program will lead to an infinite loop is known as the halting problem, and establishes absolute limits on what is computable.) Yet, when the composer induces feedback into synthesized sound structures, the ear can hear it as a single sound; when a graphical feedback loop is established in a visual syntax, the mind can apprehend the loop as a whole as a single gestalt. Of course to do so, time must not be constrained. It is difficult to see how an aural syntax, subject to real-time constraints, could accommodate feedback loops.

A diagram syntax is notably non-linear. While this is an important point, one must be careful to avoid going too far in pushing non-linearity as a distinction between a diagram syntax and the conventional speech syntax. The essence of syntax is its ability to convey logical relationships across a distance of intervening words; one might say syntax has been our way out of the bind of achieving complex speech structures in the face of the constraint of linear time. Conventional syntax provides a start toward obtaining full non-linearity from an inherently linear channel; a diagram syntax can break free completely to non-linearity without restraint. Non-linearity is freed to extend far down into the fine structure of language – just barely above the word. Or, to put it slightly differently:

2. The Interactive Juxtaposition

But how to actually achieve juxtaposition of words – to place them literally on top of one another – and sacrifice nothing in the way of intelligibility? Too often we think of words simply as whatever comes out of a word processor – or perhaps one should call it a word constrainer, forcing as it does the words into the familiar linear chains (with a nod to non-linearity by allowing hypertext links) and certainly not allowing words to be one atop another! A graphics program, on the other hand, allows text objects to be placed on top of one another with complete graphical freedom, but the legibility problem remains. Yet the graphics program gives a clue: juxtaposition combined with intelligibility is achieved (at last) by using interactive software. In a construction I call a simultaneity, words are placed in the same location – with all the freedom and fluidity a graphics program allows. At first it appears the words are simply overlaying one another – with no solution at all to the problem of overlay plus legibility. In this state the simultaneity may be called closed. The act of opening the simultaneity consists of moving the cursor using the mouse to a particular ‘hot spot’ on the screen. When the cursor enters this hot spot, all layers of the simultaneity but one are hidden: the one visible layer can be read unimpeded by its partners in the juxtaposition.

Figure 2: Taking the Diagram Interactive: Hypertext as a Medium of Thought.

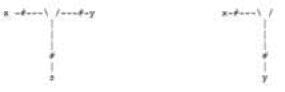

Figure 2 shows a simultaneity from Intergrams.3 In 2a the simultaneity is closed and all layers are visible; in the detail views 2b-2e the simultaneity is opened showing each layer. (A static illustration cannot convey the tactile aspects of causing the different elements to appear by moving the mouse with one’s hand; the reader will have to try to imagine this.)

A diagram is a marvellous instrument for presenting information of great complexity in a small space – to the point that the phrase ‘Well, you’ll have to draw me a diagram’ is a stereotype epithet of complaint that something is too complex. There are limitations to diagrams, however. What happens when the space required is not small? How does one manage a diagram comprising thousands of elements? Enter hypertext.4

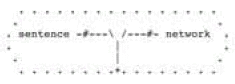

Hypertext is most often thought of as a special kind of computer software – or as the documents produced using that software, but here I would like to consider the idea of hypertext as virtual diagram. In the classical model of hypertext, a document is structured as a network of nodes and links. The nodes are typically either entire documents, or document regions (known as anchors); a link is a relationship between document places such that clicking on the anchor at the source end automatically takes the user to the destination anchor. If a hypertext is small enough and simple enough, the entire network can be represented by other means than using a computer – on paper, for instance.

Often hypertext begins (alas) at the level of the document; such documents are fully linear and use completely traditional methods for structuring text internally. Using links, associations are built up among places in these d...