- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

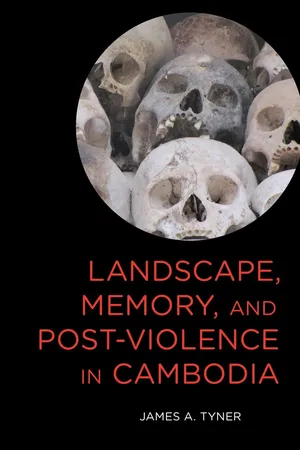

Landscape, Memory, and Post-Violence in Cambodia

About this book

Between 1975 and 1979 the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia enacted a program of organized mass violence that resulted in the deaths of approximately one quarter of the country's population. Over two million people died from torture, execution, disease and famine. From the commodification of the 'killing fields' of Choeung Ek to the hundreds of unmarked mass graves scattered across the country, violence continues to shape the Cambodian landscape.

Landscape, Memory, and Post-Violence in Cambodia explores the on-going memorialization of violence. As part of a broader engagement with war, violence and critical heritage studies, it explores how a legacy of organized mass violence becomes part of a cultural heritage and, in the process, how this heritage is 'produced'. Existing literature has addressed explicitly the impact of war and armed conflict on cultural heritage through the destruction of heritage sites. This book inverts this concern by exploring what happens when sites of 'heritage violence' are under threat. It argues that the selective memorialization of Cambodia's violent heritage negates the everyday lived experiences of millions of Cambodians and diminishes the efforts to bring about social justice and reconciliation. In doing so, it develops a grounded conceptual understanding of post-violence in conflict zones internationally.

Landscape, Memory, and Post-Violence in Cambodia explores the on-going memorialization of violence. As part of a broader engagement with war, violence and critical heritage studies, it explores how a legacy of organized mass violence becomes part of a cultural heritage and, in the process, how this heritage is 'produced'. Existing literature has addressed explicitly the impact of war and armed conflict on cultural heritage through the destruction of heritage sites. This book inverts this concern by exploring what happens when sites of 'heritage violence' are under threat. It argues that the selective memorialization of Cambodia's violent heritage negates the everyday lived experiences of millions of Cambodians and diminishes the efforts to bring about social justice and reconciliation. In doing so, it develops a grounded conceptual understanding of post-violence in conflict zones internationally.

Information

Chapter 1

‘Dig a Hole and Bury the Past’

Some 60 km south of Phnom Penh, nestled among the gently rolling hills of Kampot Province, sits an altogether unremarkable earthen structure. Spanning nearly 12 km in length, 15 m in height, and 20 m in width, what remains of the Koh Sla dam seems at peace among the short grass and scrub, its flanks crisscrossed by narrow dirt footpaths connecting the stilt houses that dot the scene. The villagers who tend the rice fields and fish in the surrounding ponds anchor Koh Sla in the outwardly timeless landscape of rural Cambodia (figure 1.1).

But the tranquil repose of this earthwork in such a halcyon setting belies a darker, more violent past. Under the vegetation that covers its canted bulk—beneath the sediment of intervening years—lingers a history of famine, disease, exposure, and mass murder. Nine thousand men, women, and children perished here, killed, or left to die at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. However, unlike other sites of brutality and mass violence associated with the Cambodian genocide, the landscape of Koh Sla bears no consecration. No signs give voice to its past. No memorial structure marks the graves of its builders: their forced labor, starvation, hardship, and death remain absent from the popular narratives of mass violence in Cambodia. No tour buses idle nearby and no tourists snap photographs. In a country that has sought ostensibly to illuminate, explain, and at times commodify its violent past, Koh Sla’s history is remarkable precisely for being so unremarked.

As a site of ruination1 Koh Sla was ‘discovered’ 28 years after the fall of the Khmer Rouge. On 5 May 2007 a group of Vietnamese delegates, Cambodian provincial and district authorities, and local villagers began excavating a suspected grave site of former Vietnamese soldiers located near Sre Lieu village in the Chhouk district of Kampot Province.2 During the exhumation, however, various items of jewelry and gold were also found. Subsequently, hundreds of villagers began to unearth the area in search of instant wealth. One man in his thirties explained: “I try to dig and look around, hoping that good luck will fall on me and bring me gold.”3

Figure 1.1 Landscape around Koh Sla Dam, Kampot Province, Cambodia. Source: Photograph by James Tyner.

As news of the grave site spread, older men and women—survivors of the violence—began to share stories of its hidden secret. In 1973 Khmer Rouge cadre began work on a massive infrastructure near Sre Lieu. Kampot Province had recently been liberated by the Khmer Rouge and local residents were quickly enlisted—forced—to participate in the construction of the Koh Sla dam. Conditions were horrendous, with many people dying. Indeed, so high was the mortality that the Khmer Rouge established a mobile hospital (designated as Zone 35 Hospital) at the site. However, because of inadequate medical personnel and proper medicines, few patients actually received adequate care. In fact, survivors recall that patients were just as likely to die of improper medicines and medical practice as they were from disease.4 According to Ngay Yong, a former member of a mobile work unit who labored at Koh Sla, “I think that very few people died of illness. Rather, most of them died as a result of the lethal injections they were given at the Zone 35 Hospital.”5

Under the Khmer Rouge, medicine and health care (very broadly defined) were not eliminated—despite claims to the contrary. David Chandler, for example, states that the Khmer Rouge rejected Western-style medicine and refused to import medicine.6 However, surviving documents archived at the Documentation Center of Cambodia7 indicate clearly that substantial amounts of Western-style medicines were imported from Thailand, China, Hong Kong, and elsewhere and that medicines and pharmaceuticals of varying qualities were ‘available’ throughout Democratic Kampuchea—as Cambodia was renamed by the Khmer Rouge.8 For example, sizable quantities of penicillin, quinine, serum, and vitamins were imported by the Khmer Rouge.9 These were subsequently warehoused in Phnom Penh and Kampong Som before being distributed to various hospitals and clinics.10

Moreover, these documents establish that the inadequate provision of health care was widely known among high-ranking officials. To this end, one document in particular stands out.11 It consists of notes taken during a meeting attended by key cadre, including Pol Pot, Nuon Chean, Khieu Samphon, and Ieng Thirith.12 The occasion of the meeting, held on 10 June 1976, was to discuss solutions to the health ‘crises’ in Democratic Kampuchea. At one point during the meeting, Pol Pot addressed the need for medicine within the country. He explained that pharmaceutical factories had been established, but that the manufacture of medicines was hindered by a lack of raw materials.13 Pol Pot proposed two solutions: the first was to purchase raw materials from other countries, while the second was to collect materials from within Cambodia. Within two months of that meeting, the Ministry of Commerce—supervised by Vorn Vet—began importing raw materials from Hong Kong, North Korea, and China for the purpose of producing medicines.14

At Sre Lieu medicines were available, but for the vast majority of forced laborers, the quality and quantity were insufficient. Consequently, as work on the dam progressed, conditions worsened. Additional work brigades were deployed to the site and work continued through 1977. Malaria and cholera were rampant; many other men and women died from injuries. Srey Neth, a survivor who worked at the dam site, was assigned to bury the members of her unit who died. She recalls: “I was forbidden [by the Khmer Rouge] from telling others about the number of deaths.” She explains that “sometimes they [the Khmer Rouge] woke me up in the middle of the night and ordered me to take bodies to be buried. . . . The number of bodies I buried ranged from two to six per night.”15

“An environment of ruins,” Yael Navaro-Yashin writes, “discharges an affect of melancholy. At the same time, those who inhabit this space of ruins feels melancholic: they put the ruins into discourse, symbolize them, interpret them, politicize them, understand them, project their subjective conflicts onto them, remember them, try to forget them, historicize them, and so on.”16 Decades later the exhumation of the dead at Sre Lieu causes Srey Neth to contemplate the past. When in her twenties she carried the corpses of her friends to the graves; now at fifty she laments: “I cannot recognize which bones belong to my colleagues, whose bodies I buried.” She explains: “I would like to ask for forgiveness from the victims if I was neglectful in burying their bodies.”17

In the days and weeks following the ‘discovery’ and excavation of the graves, local authorities attempted to control the practice of grave-robbing. Subdistrict chief Suon Phorn stated that he was against the idea of digging for gold because unearthing the graves would disturb the victims’ spirits; Khoem Yukhoeun, an assistant to Suon Phorn, likewise expressed his regret, explaining that “the villagers should not have unearthed the graves thoughtlessly. It is not good if the villagers selfishly continue digging the graves for gold.”18

Koh Sla dam and the attendant mass graves near the village of Sre Lieu provide the impetus for this present work. In 1998 the long-standing prime minister of Cambodia, Hun Sen, expressed his belief that it was time to “dig a hole and bury the past.”19 His now infamous comment, hauntingly evocative of the thousands of unmarked mass graves that dot Cambodia’s landscape, is especially salient for it calls attention to the place of violence as part of a living cultural heritage. Between 1975 and 1979 Cambodia was witness to a program of organized mass violence that resulted in the death of approximately one-quarter of the country’s population. Upward of two million men, wome...

Table of contents

- Cover-Page

- Halftitle

- 1 ‘Dig a Hole and Bury the Past’

- 2 ‘Their Bones Have Piled Up’

- 3 ‘More Than I Can Speak’

- 4 ‘Only If Pregnant Women Were Killed’

- 5 ‘They Just Kept Bombing’

- 6 ‘They Are Murderous Thugs’

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Landscape, Memory, and Post-Violence in Cambodia by James A. Tyner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.