![]()

Part One

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

An enormous toy full of subtleties

What surprised the Parisians, standing in little groups along the Champs-Elysées to watch the German soldiers take over their city in the early hours of 14 June 1940, was how youthful and healthy they looked. Tall, fair, clean shaven, the young men marching to the sounds of a military band to the Arc de Triomphe were observed to be wearing uniforms of good cloth and gleaming boots made of real leather. The coats of the horses pulling the cannons glowed. It seemed not an invasion but a spectacle. Paris itself was calm and almost totally silent. Other than the steady waves of tanks, motorised infantry and troops, nothing moved. Though it had rained hard on the 13th, the unseasonal great heat of early June had returned.

And when they had stopped staring, the Parisians returned to their homes and waited to see what would happen. A spirit of attentisme, of holding on, doing nothing, watching, settled over the city.

The speed of the German victory—the Panzers into Luxembourg on 10 May, the Dutch forces annihilated, the Meuse crossed on 13 May, the French army and airforce proved obsolete, ill-equipped, badly led and fossilised by tradition, the British Expeditionary Force obliged to fall back at Dunkirk, Paris bombed on 3 June—had been shocking. Few had been able to take in the fact that a nation whose military valour was epitomised by the battle of Verdun in the First World War and whose defences had been guaranteed by the supposedly impregnable Maginot line, had been reduced, in just six weeks, to a stage of vassalage. Just what the consequences would be were impossible to see; but they were not long in coming.

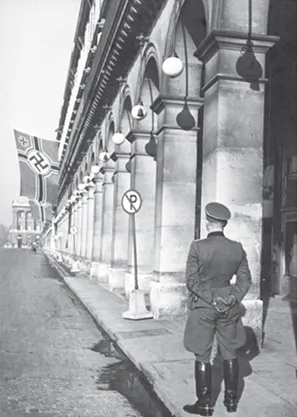

By midday on the 14th, General Sturnitz, military commandant of Paris, had set up his headquarters in the Hotel Crillon. Since Paris had been declared an open city there was no destruction. A German flag was hoisted over the Arc de Triomphe, and swastikas raised over the Hôtel de Ville, the Chamber of Deputies, the Senate and the various ministries. Edith Thomas, a young Marxist historian and novelist, said they made her think of ‘huge spiders, glutted with blood’. The Grand Palais was turned into a garage for German lorries, the École Polytechnique into a barracks. The Luftwaffe took over the Grand Hotel in the Place de l’Opéra. French signposts came down; German ones went up. French time was advanced by one hour, to bring it into line with Berlin. The German mark was fixed at almost twice its pre-war level. In the hours after the arrival of the occupiers, sixteen people committed suicide, the best known of them Thierry de Martel, inventor in France of neurosurgery, who had fought at Gallipoli.

The first signs of German behaviour were, however, reassuring. All property was to be respected, providing people were obedient to German demands for law and order. Germans were to take control of the telephone exchange and, in due course, of the railways, but the utilities would remain in French hands. The burning of sackfuls of state archives and papers in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, carried out as the Germans arrived, was inconvenient, but not excessively so, as much had been salvaged. General von Brauchtisch, commander-in-chief of the German troops, ordered his men to behave with ‘perfect correctness’. When it became apparent that the Parisians were planning no revolt, the curfew, originally set for forty-eight hours, was lifted. The French, who had feared the savagery that had accompanied the invasion of Poland, were relieved. They handed in their weapons, as instructed, accepted that they would henceforth only be able to hunt rabbits with terriers or stoats, and registered their much-loved carrier pigeons. The Germans, for their part, were astonished by the French passivity.

When, over the next days and weeks, those who had fled south in a river of cars, bicycles, hay wagons, furniture vans, ice-cream carts, hearses and horse-drawn drays, dragging behind them prams, wheelbarrows and herds of animals, returned, they were amazed by how civilised the conquerors seemed to be. There was something a little shaming about this chain reaction of terror, so reminiscent of the Grand Peur that had driven the French from their homes in the early days of the revolution of 1797. In 1940 it was not, after all, so very terrible. The French were accustomed to occupation; they had endured it, after all, in 1814, 1870 and 1914, and then there had been chaos and looting. Now they found German soldiers in the newly reopened Galeries Lafayette, buying stockings and shoes and scent for which they scrupulously paid, sightseeing in Notre Dame, giving chocolates to small children and offering their seats to elderly women on the métro.

Soup kitchens had been set up by the Germans in various parts of Paris, and under the flowering chestnut trees in the Jardin des Tuileries, military bands played Beethoven. Paris remained eerily silent, not least because the oily black cloud that had enveloped the city after the bombing of the huge petrol dumps in the Seine estuary had wiped out most of the bird population. Hitler, who paid a lightning visit on 28 June, was photographed slapping his knee in delight under the Eiffel Tower. As the painter and photographer Jacques Henri Lartigue remarked, the German conquerors were behaving as if they had just been presented with a wonderful new toy, ‘an enormous toy full of subtleties which they do not suspect’.

On 16 June, Paul Reynaud, the Prime Minister who had presided over the French government’s flight from Paris to Tours and then to Bordeaux, resigned, handing power to the much-loved hero of Verdun, Marshal Pétain. At 12.30 on the 17th, Pétain, his thin, crackling voice reminding Arthur Koestler of a ‘skeleton with a chill’, announced over the radio that he had agreed to head a new government and that he was asking Germany for an armistice. The French people, he said, were to ‘cease fighting’ and to co-operate with the German authorities. ‘Have confidence in the German soldier!’ read posters that soon appeared on every wall.

The terms of the armistice, signed after twenty-seven hours of negotiation in the clearing at Rethondes in the forest of Compiègne in which the German military defeat had been signed at the end of the First World War, twenty-two years before, were brutal. The geography of France was redrawn. Forty-nine of France’s eighty-seven mainland departments—three-fifths of the country—were to be occupied by Germany. Alsace and Lorraine were to be annexed. The Germans would control the Atlantic and Channel coasts and all areas of important heavy industry, and have the right to large portions of French raw materials. A heavily guarded 1,200-kilometre demarcation line, cutting France in half and running from close to Geneva in the east, west to near Tours, then south to the Spanish border, was to separate the occupied zone in the north from the ‘free zone’ in the south, and there would be a ‘forbidden zone’ in the north and east, ruled by the German High Command in Brussels. An exorbitant daily sum was to be paid over by the French to cover the costs of occupation. Policing of a demilitarised zone along the Italian border was to be given to the Italians—who, not wishing to miss out on the spoils, had declared war on France on 10 June.

The French government came to rest in Vichy, a fashionable spa on the right bank of the river Allier in the Auvergne. Here, Pétain and his chief minister, the appeaser and pro-German Pierre Laval, set about putting in place a new French state. On paper at least, it was not a German puppet but a legal, sovereign state with diplomatic relations. During the rapid German advance, some 100,000 French soldiers had been killed in action, 200,000 wounded and 1.8 million others were now making their way into captivity in prisoner-of-war camps in Austria and Germany, but a new France was to rise out of the ashes of the old. ‘Follow me,’ declared Pétain: ‘keep your faith in La France Eternelle’. Pétain was 84 years old. Those who preferred not to follow him scrambled to leave France—over the border into Spain and Switzerland or across the Channel—and began to group together as the Free French with French nationals from the African colonies who had argued against a negotiated surrender to Germany.

In this France envisaged by Pétain and his Catholic, conservative, authoritarian and often anti-Semitic followers, the country would be purged and purified, returned to a mythical golden age before the French revolution introduced perilous ideas about equality. The new French were to respect their superiors and the values of discipline, hard work and sacrifice and they were to shun the decadent individualism that had, together with Jews, Freemasons, trade unionists, immigrants, gypsies and communists, contributed to the military defeat of the country.

Returning from meeting Hitler at Montoire on 24 October, Pétain declared: ‘With honour, and to maintain French unity… I am embarking today on the path of collaboration’. Relieved that they would not have to fight, disgusted by the British bombing of the French fleet at anchor in the Algerian port of Mers-el-Kebir, warmed by the thought of their heroic fatherly leader, most French people were happy to join him. But not, as it soon turned out, all of them.

Long before they reached Paris, the Germans had been preparing for the occupation of France. There would be no gauleiter—as in the newly annexed Alsace-Lorraine—but there would be military rule of a minute and highly bureaucratic kind. Everything from the censorship of the press to the running of the postal services was to be under tight German control. A thousand railway officials arrived to supervise the running of the trains. France was to be regarded as an enemy kept in faiblesse inférieure, a state of dependent weakness, and cut off from the reaches of all Allied forces. It was against this background of collaboration and occupation that the early Resistance began to take shape.

A former scoutmaster and reorganiser of the Luftwaffe, Otto von Stülpnagel, a disciplinarian Prussian with a monocle, was named chief of the Franco-German Armistice Commission. Moving into the Hotel Majestic, he set about organising the civilian administration of occupied France, with the assistance of German civil servants, rapidly drafted in from Berlin. Von Stülpnagel’s powers included both the provisioning and security of the German soldiers and the direction of the French economy. Not far away, in the Hotel Crillon in the rue de Rivoli, General von Sturnitz was busy overseeing day to day life in the capital. In requisitioned hotels and town houses, men in gleaming boots were assisted by young German women secretaries, soon known to the French as ‘little grey mice’.

There was, however, another side to the occupation, which was neither as straightforward, nor as reasonable; and nor was it as tightly under the German military command as von Stülpnagel and his men would have liked. This was the whole apparatus of the secret service, with its different branches across the military and the police.

After the protests of a number of his generals about the behaviour of the Gestapo in Poland, Hitler had agreed that no SS security police would accompany the invading troops into France. Police powers would be placed in the hands of the military administration alone. However Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, the myopic, thin-lipped 40-year-old Chief of the German Police, who had long dreamt of breeding a master race of Nordic Ayrans, did not wish to see his black-shirted SS excluded. He decided to dispatch to Paris a bridgehead of his own, which he could later use to send in more of his men. Himmler ordered his deputy, Reinhard Heydrich, the cold-blooded head of the Geheime Staatspolizei or Gestapo, which he had built up into an instrument of terror, to include a small group of twenty men, wearing the uniform of the Abwehr’s secret military police, and driving vehicles with military plates.

In charge of this party was a 30-year-old journalist with a doctorate in philosophy, called Helmut Knochen. Knochen was a specialist in Jewish repression and spoke some French. After commandeering a house on the avenue Foch with his team of experts in anti-terrorism and Jewish affairs, he called on the Paris Prefecture, where he demanded to be given the dossiers on all German émigrés, all Jews, and all known anti-Nazis. Asked by the military what he was doing, he said he was conducting research into dissidents.

Knochen and his men soon became extremely skilful at infiltration, the recruitment of informers and as interrogators. Under him, the German secret services would turn into the most feared German organisation in France, permeating every corner of the Nazi system.

Knochen was not, however, alone in his desire to police France. There were also the counter-terrorism men of the Abwehr, who reported back to Admiral Canaris in Berlin; the Einsatzstab Rosenberg which ferreted out Masonic lodges and secret societies and looted valuable art to be sent off to Germany, and Goebbels’s propaganda specialists. Von Ribbentrop, the Minister for Foreign Affairs in Berlin, had also persuaded Hitler to let him send one of his own men to Paris, Otto Abetz, a Francophile who had courted the French during the 1930s with plans for Franco-German co-operation. Abetz was 37, a genial, somewhat stout man, who had once been an art master, and though recognised to be charming and to love France, was viewed by both French and Germans with suspicion, not least because his somewhat ambiguous instructions made him ‘responsible for political questions in both occupied and unoccupied France’. From his sumptuous embassy in the rue de Lille, Abetz embarked on collaboration ‘with a light touch’. Paris, as he saw it, was to become once again the cité de lumière, and at the same time would serve as the perfect place of delight and pleasure for its German conquerors. Not long after visiting Paris, Hitler had declared that every German soldier would be entitled to a visit to the city.

Despite the fact that all these separate forces were, in theory, subordinated to the German military command, in practice they had every intention of operating independently. And, when dissent and resistance began to grow, so the military command was increasingly happy to let the unofficial bodies of repression deal with any signs of rebellion. Paris would eventually become a little Berlin, with all the rivalries and clans and divisions of the Fatherland, the difference being that they shared a common goal: that of dominating, ruling, exploiting and spying on the country they were occupying.

Though the French police—of which there were some 100,000 throughout France in the summer of 1940—had at first been ordered to surrender their weapons, they were soon instructed to take them back, as it was immediately clear that the Germans were desperately short of policemen. The 15,000 men originally working for the Paris police were told to resume their jobs, shadowed by men of the Feldkommandatur. A few resigned; most chose not to think, but just to obey orders; but there were others for whom the German occupation would prove a step to rapid promotion.

The only German police presence that the military were tacitly prepared to accept as independent of their control was that of the anti-Jewish service, sent by Eichmann, under a tall, thin, 27-year-old Bavarian called Theo Dannecker. By the end of September, Dannecker had also set himself up in the avenue Foch and was making plans for what would become the Institut d’Etudes des Questions Juives. His job was made infinitely easier when it became clear that Pétain and the Vichy government were eager to anticipate his wishes. At this stage in the war, the Germans were less interested in arresting the Jews in the occupied zone than in getting rid of them by sending them to the free zone, though Pétain was no less determined not to have them. According to a new census, there were around 330,000 Jews living in France in 1940, of which only half were French nationals, the others having arrived as a result of waves of persecution across Europe.

At the time of the 1789 revolution, France had been the first country to emancipate and integrate its Jews as French citizens. All through the 1920s and 1930s the country had never distinguished between its citizens on the basis of race or religion. Within weeks of the German invasion, posters were seen on Parisian walls with the words ‘Our enemy is the Jew’. Since the Germans felt that it was important to maintain the illusion—if illusion it was—that anti-Jewish measures were the result of direct orders by the Vichy government and stemmed from innate French anti-Semitism, Dannecker began by merely ‘prompting’ a number of ‘spontaneous’ anti-Jewish demonstrations. ‘Young guards’ were secretly recruited to hang about in front of Jewish shops to scare customers away. In early August, they ransacked a number of Jewish shops. On the 20th, a grande action saw the windows of Jewish sho...