![]()

1

Engagement and Campus Capital

When Carolina started at Millbrook, she was nervous about taking chemistry. She knew she needed to take it to meet her pre-med degree requirements, but she was nervous about passing it. Her high school chemistry class wasn’t hard and she had a feeling that was because she didn’t learn much. After a few weeks, Carolina grew to really like her chemistry professor, Dr. Arroyo. He was an engaging professor and really seemed to take an interest in his students. However, although she really enjoyed Dr. Arroyo as a person, she found his class difficult. After not doing well on a few tests, Carolina made an appointment to speak with him about her struggles with the content. It was then, at his office hours, that Carolina learned that Dr. Arroyo was also the first person in his family to go to college and even got his PhD! Carolina was especially surprised to learn that, like her, Dr. Arroyo was originally from New York City. In fact, Carolina knew the high school he had attended because her cousin went there. Carolina really appreciated knowing that she had a lot in common with one of her professors.

During this first meeting, and several that followed, Carolina described not being able to handle the work in his class. At first, Dr. Arroyo tried to give Carolina suggestions for studying and learning the new content. He introduced her to an upper-class Chemistry major to give her additional tutoring; however, it didn’t seem to help. She continued to feel confused and lost in the course. At one point, Dr. Arroyo started to ask questions about why Carolina had picked pre-med as her major. The more she tried to answer him, the more she and Dr. Arroyo realized that perhaps she should consider some other options. Over the next few months, Dr. Arroyo helped Carolina transition from pre-med to English. What a difference! Before too long Carolina was loving her classes and earning strong marks in all of her courses. She felt much better, and even though she earned a C- in chemistry she still considered Dr. Arroyo a mentor.

First-generation college students (FGCS) like Carolina often struggle academically and are more likely to withdraw from college before completing their degrees at rates higher than those of their peers with college-educated parents. We know that in order to improve their persistence, colleges and universities should provide FGCS opportunities to acquire the academic capital that positively affects persistence (Chen, 2005; Engle & Tinto, 2008; St. John, Hu, & Fisher, 2010). Researchers have identified processes that can develop academic capital, processes that include acquiring knowledge about navigating campus and the development of informational and supportive relational networks and behaviors (St. John, Hu, & Fisher, 2010). Structural factors like lack of access to mentors have also been identified as key concerns in improving FGCS and working-class student postsecondary persistence (Stephens et al., 2015). Relationships and communication with parents, teachers, and counselors are deemed highly supportive and influential for FGCS and low-socioeconomic status (SES) college students, and yet these are students who typically do not have the information or social capital to provide instrumental support to FGCS (Sy et al., 2011). These structural factors support and reproduce dominant group norms that are often outside the awareness of FGCS. These norms are prized and assigned value in educational settings and are understood as social capital. Non-dominant and socially marginalized groups in educational settings are frequently challenged to take on these norms, often as a result of limited information, incomplete knowledge, and/or lack of access to individuals who hold such capital (Stanton-Salazar, 1997).

As mentioned in the Introduction, colleges and universities engage in interventions designed to improve the persistence rates of first-generation college students by focusing on the logistical challenges of navigating college that these students face. For example, institutional practices and programs such as learning communities and peer-mentoring programs aim to communicate information and develop FGCS awareness of the many practices and procedures common on campus, but normally focus on developing academic and study skills (Bettinger & Long, 2005). However, research on the effectiveness of these conventional programs suggests that they can be ineffective (Charles A. Dana Center, 2012). Historically, these interventions have employed conventional face-to-face (F2F) strategies that do not take advantage of up-to-date Web 2.0 applications and mobile technologies, conceivably limiting FGCS ability to engage with the twenty-first-century college campus.

In many colleges and universities, programs to address FGCS transition to college, in particular, those aimed at improving their academic preparation and engagement, attempt to transmit social capital through instructor, staff, and peer mentorship relationships. In these varied programs, the primary goal is most often to improve FGCS persistence and success in college by increasing the relevant social capital of FGCS through F2F relationships. Courses and workshops on study skills and academic writing and on navigating curricular requirements are the centerpieces of most of these programs. Colleges and universities rightly have looked to relationships to transmit social capital to FGCS, but have done so through traditional means. What about the new relational spaces that now characterize our campuses? For example, as a new relational space can social media serve to transmit social capital? Early research on Facebook and social capital transmission showed a strong association between Facebook use as a means to obtain social capital, especially social capital or information that benefits the user in some way (Ellison, Steinfeld, & Lampe, 2007). Are social media another means to access the forms of capital that FGCS critically need to achieve academic success on campus? Could Carolina’s use of Facebook enable access to resources or information like she obtained from Dr. Arroyo?

The experiential and cultural backgrounds of FGCS are most often disparate from those of continuing generation college students (CGCS). FGCS are often racial and ethnic minorities, usually come from low-income families (Chen, 2005), and typically have differential educational outcomes (as traditionally measured) (Pike & Kuh, 2005; Terenzini et al., 1996; Tym et al., 2004). The funds of knowledge FGCS bring to college reflect their non-college-going familial backgrounds and those social and economic forces that limit access to the full range of social capital traditionally associated with effective college-going. Often, there is not an obvious and precise correspondence between FGCS funds of knowledge, or cultural capital (Moll et al., 1992), and the social capital necessary for efficacious college-going. Consequently, as Dewey (1915) observed, educational institutions should seek the “keys which will unlock to the [student] the wealth of social capital which lies beyond the possible range of his limited individual experience” (p. 104).

In the twenty-first century, is technology the key to unlock the wealth of social capital beyond FGCS experience? Can tablet technology (like the iPad) and social media prove effective keys to unlock the means to access social capital on campus that is particularly relevant to FGCS? Early research on Internet communication suggested that users could gain emotional and instrumental support communicating on online networks (Wellman et al., 2003). Through connection strategies (Ellison, Steinfeld, & Lampe, 2011), social media may be a mechanism that colleges and universities could use to enable FGCS to build a network of capital-rich relationships. Current research indicates that social media are essential for a group of people to communicate purposes, to provide guidance and support for new members, to supply members with useful information and opportunities for personal growth and development, and to serve as a conduit for interaction between and among members so that they actively construct the community’s culture (Martínez Alemán & Wartman, 2009; Nagele, 2005). Tapping their networked relationships for information and social and emotional counsel on social media sites like Facebook can positively affect self-esteem among lower-self-esteem users (Steinfield, Ellison, & Lampe, 2008). Facebook is understood as a site in which users draw on their network relationships for social capital (Brooks et al., 2014). Facebook users can derive more value from their online connections when they recognize that these relationships are resources of valued social capital (Burke, Kraut, & Marlow, 2011).

But how are we to understand technology and social media as keys to expanding FGCS access to social capital on campus? How are the distinctive capacities of tablet technology and social media well suited to address the unique social capital needs of FGCS? To answer these questions, one must consider the conceptual basis for these inquiries. This chapter examines what we mean by social capital, why access to social capital is so critical for FGCS, and why new technologies are specifically intended to extend users’ social capital reach.

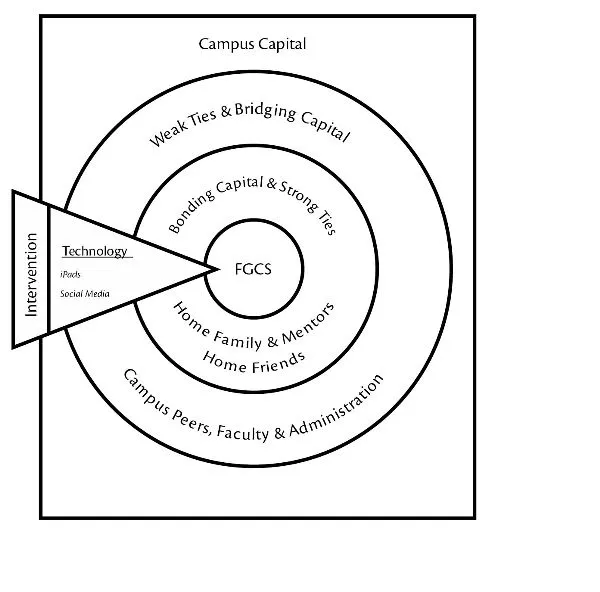

Our Conceptual Framework: Campus Capital

Threading together knowledge of FGCS and student engagement, Web 2.0 technologies, and social capital acquisition theories, our research project proposed a conceptual framework, “campus capital” (Figure 1.1). An inclusive term that consists of the various forms of social capital that enhance students’ on-campus experiences that researchers have documented affect their persistence to graduation (Horvat, 2000; Pascarella et al., 2004; Walpole, 2003) through relational networks, campus capital enabled us to view and examine the various ways in which FGCS access social capital through Web 2.0 technologies. We define “campus capital” as those forms of explicit and implicit social capital specific to a particular campus. In this way, campus capital is derived from a framing of FGCS experiential reality through critical standpoints and theories of social capital acquisition, and the relationship between online social networking and social capital acquisition.

Our conceptualization of campus capital is informed by critical theorists, especially those focused on social capital acquisition. Critical theorists have sought to challenge the many different ways that individuals and groups are suppressed in communities. Horkheimer (1982) intended critical theory as a way to explain the conditions in which an individual’s agency was diminished by social structures. Foundationally, critical theory was aimed at offering options to extend and expand individual agency in all manner of social existence. Historically concerned with the ways in which capitalism as a social structure decreased individual agency, critical theory nonetheless evolved to enlarge its view of social inequality through Habermas’s (1981, 1987) consideration of the role of symbols and language in determining social inequality and Levi-Strauss’s (1963) critical anthropology that put forth a view of culture as a system of symbolic communication that circulates in institutions to produce patterns of behavior, values, and traditions that reinforce hierarchies and restrict agency. But it is Bourdieu’s (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977; Bourdieu,1986) formulation of communication and culture as regulatory that has enabled us to identify the many ways in which colleges and universities are institutions in which FGCS access to campus capital is regulated through institutional culture, and the ways in which online social networks can aid in the acquisition of campus capital.

Social Capital in the Campus Context

From Bourdieu’s (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977; Bourdieu, 1986) critical perspective, a college or university is a multifaceted social space occupied by students, faculty, and staff, all individuals who communicate through a complex network of relationships. As individuals occupying this social space, students transmit knowledge and information through their network of relationships on campus. Through language (symbolic or otherwise) and behavior (action or inaction), individual students produce, transmit, and consume information, or, in Bourdieu’s lexicon, capital. Capital is communicated through an individual’s network of relationships on campus and its value is dependent on its utility in the social space, the campus. Students can transmit capital that Bourdieu would characterize as cultural capital or insider (tacit) knowledge that is derived from a student’s membership in a particular class or group. In the case of college students, cultural capital can take the form of tacit knowledge that is the result of their own personal or family’s social/economic class status, and/or their experiences with college culture prior to attending college themselves. Students may have college-educated parents who transmit cultural capital to them. This capital can include knowledge about living in the residence halls, attending class, choosing a major, or how to speak to and interact with faculty. College students may have siblings with college experience who also transmit cultural capital about college through the family’s relational network. Students themselves may have first-hand experience of college because they attended a university’s summer program while in high school, and/or may have received comparable cultural capital living independently at sleep-away camps or in high school exchange programs. Further, the contacts and memberships that students have before they enter college and those that they form while in college are sources of a form of cultural capital, social capital, that can be transmitted and leveraged in college.

Bourdieu’s claim that forms of capital are regulated by educational institutions through norms, customary conduct, and activities (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977) suggests that on campus individual students and groups of students may be experientially and structurally positioned outside the networks of relationships through which campus capital is transmitted and/or shared. Insiders to the culture of higher education and the culture of a particular campus possess, transmit, and leverage campus capital, effectively exercising their autonomy and agency because they possess that capital. Possessing campus capital enables individual agency. With campus capital, students can act autonomously and are not dependent on or subjugated by those students with capital. Outsiders to prevailing college culture may lack campus capital that is normative on campus, though they may possess different social knowledge and forms of capital. But more importantly, their agency on campus is diminished if the lack of campus capital restricts resource acquisition. Like Bourdieu’s characterization of socioeconomic class as a matrix of resource inequality, students who do not have access to the full range of campus capital and its circulation find their agency constrained. Their decisions, actions, and movement in the social space are inhibited. Their engagement with the campus is constrained.

As Davis (2010) observed, FGCS are “unfamiliar with the culture of college,” meaning the “insider knowledge, the special language, and the subtle verbal and nonverbal signals that, after one has mastered them, make one a member of any in-group, community, or subculture” (p. 29). Possessing insider knowledge gives one membership in the campus culture. Many institutions dedicate programs and services to familiarize FGCS with processes like registration and advising, but authors like Davis posit that FGCS “must also master a more profound set of skills and behaviors” that constitute the “complicated and subtle” aspects of campus culture (p. 30). Consequently, FGCS are inhibited by their limited access to resources embedded in the campus culture. Access to embedded capital is what determines individual agency and self-sufficiency, and that enables students to gain comfort and membership in the college community. A student’s access to embedded capital on campus is “an investment in social relations with expected returns” (Lin, 2001a, p. 6).

Though Davis (2010) implied that relationships and networks are important to the social capital of campus life, we use the term “campus capital” to foreground the importance and significance of social networks for college engagement, the process through which insider knowledge is acquired. Campus capital is the engrained resources in the social relations and networks of students, faculty, and staff on campus that if utilized can enrich student life. As Lin (2001b) observed, the circulation of information across social networks provides individuals with useful information about opportunities and alternatives (insider knowledge) that as outsiders they do not possess. FGCS outsider status in college cultures confirms their lack of social credentials and social capital. Additionally, as in any culture, FGCS outsider identities will be reinforced the longer they are restricted from accessing insider capital through relational networks.

Campus capital is insider knowledge and information garnered through networks that circulates and is communicated through these relational networks. Campus capital is characterized by Lin’s (2001b) elements of social capital: it is information attained through networks and gives individuals access to opportunities or decision-making that will impact their ability to claim membership in a community and that will enable them to be entitled to certain resources and community membership status. A comprehensive construct, campus capital is that network-bound knowledge and information that can “approximate being oriented intuitively” on campus (Davis, 2010, p. 33) and that serves to enhance students’ on-campus experiences and affect their persistence to graduation. As Davis (2010) correctly upheld, unlike continuing generation college students, first-generation college students do not receive insight about college-going and college culture through their close, trusted, parental, and familial relationships. Though certainly supported and motivated by these relationships, FGCS development does not cultivate an intuitive awareness that positions them within or inside college culture. Campus capital extends understanding of insider knowledge and social capital to focus on the networks of campus relationships that act as a means to obtain insider knowledge or social capital.

This intuitive awareness enables CGCS as insiders to access varied forms of capital inside and outside the classroom. Within the classroom, FGCS often feel like imposters (Hayes, 1997). Positioned as outsiders to the normative culture of the classroom by virtue of their academic under-preparation (Pascarella et al., 2004) and their lack of intuitive awareness of college classroom etiquette and protocol, FGCS are often anxious about professors’ and peers’ expectations. How and when to contribute to class discussion, and when and whether to volunteer a response or comment are behaviors that are not informed by insider capital but rather by FGCS outsider intuition. The value of argumentation for the purpose of knowledge-building may seem foreign given FGCS academic experiences in high school, as can the culture of intellectual risk-taking common in many college classrooms. The risk of being incorrect coupled with not being confident in the style of normative college classroom communication may silence FGCS (Davis, 2010). The forms and customs of expected student behavior that signal engagement in the normative culture of the college classroom, and the jargon and lexicon of both disciplinary and academic culture, is most likely unfamiliar to FGCS. FGCS may struggle in class and their success in a course may be affected by their unfamiliarity with the lexicon of academia or academic language, especially if they are English-language learners (Scarcella, 2003). Could social media like Facebook that encourage students’ collaboration and cooperation and enhance their social presences (Cheung, Chui, & Lee, 2011) prove effective for FGCS in the college classroom?

Consequently, just as in any club or organization, membership comes with certain rights, power, and privileges; however, those who do not belong are not afforded full membership, and as a consequence their range of resources and funds of knowledge can be regulated and inequitable. In a racist and oppressive society, membership in educational communities is restricted (in part) because of the regulation of cultural capital broadly understood (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977; DiMaggio, 1982; Harker, 1990; Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995). Consequently, membership in an educational community necessitates that members engage by accessing the community’s insider knowledge and its networks of social associations and connections. Accessing the community’s capital enables membership that enhances community engagement and an individual’s sense of belonging. Being a member of a community requires the means to access the community’s varied forms of capital and engagement with those processes through which social capital is expended.

In educational institutions like colleges and universities, individuals and groups h...