![]()

Part I

Introductory and Overarching Studies

![]()

1

Inventing the Final Neolithic

Colin Renfrew

After the radiocarbon revolution

The term “Final Neolithic” as applied to the prehistoric Aegean was a product of the radiocarbon revolution. It was first used, I think, by B. Phelps as he was preparing his doctoral dissertation on the Later Neolithic of South Greece.1 The need for such a term came with the radiocarbon revolution, and in particular with the tree-ring calibration of radiocarbon (the “second radiocarbon revolution”) which demolished forever the short chronology for the Greek and Balkan Neolithic.2 The latter had arisen from the alleged synchronism between Vinča and Early Troy as proposed by M. Vassits and G. Childe, and argued with considerable vigor later by V. Milojčić and M. Garašanin. When radiocarbon dates showed that Vinča long preceded Troy, the Neolithic of Greece and the Balkans was seen to extend much earlier than had previously been realised.

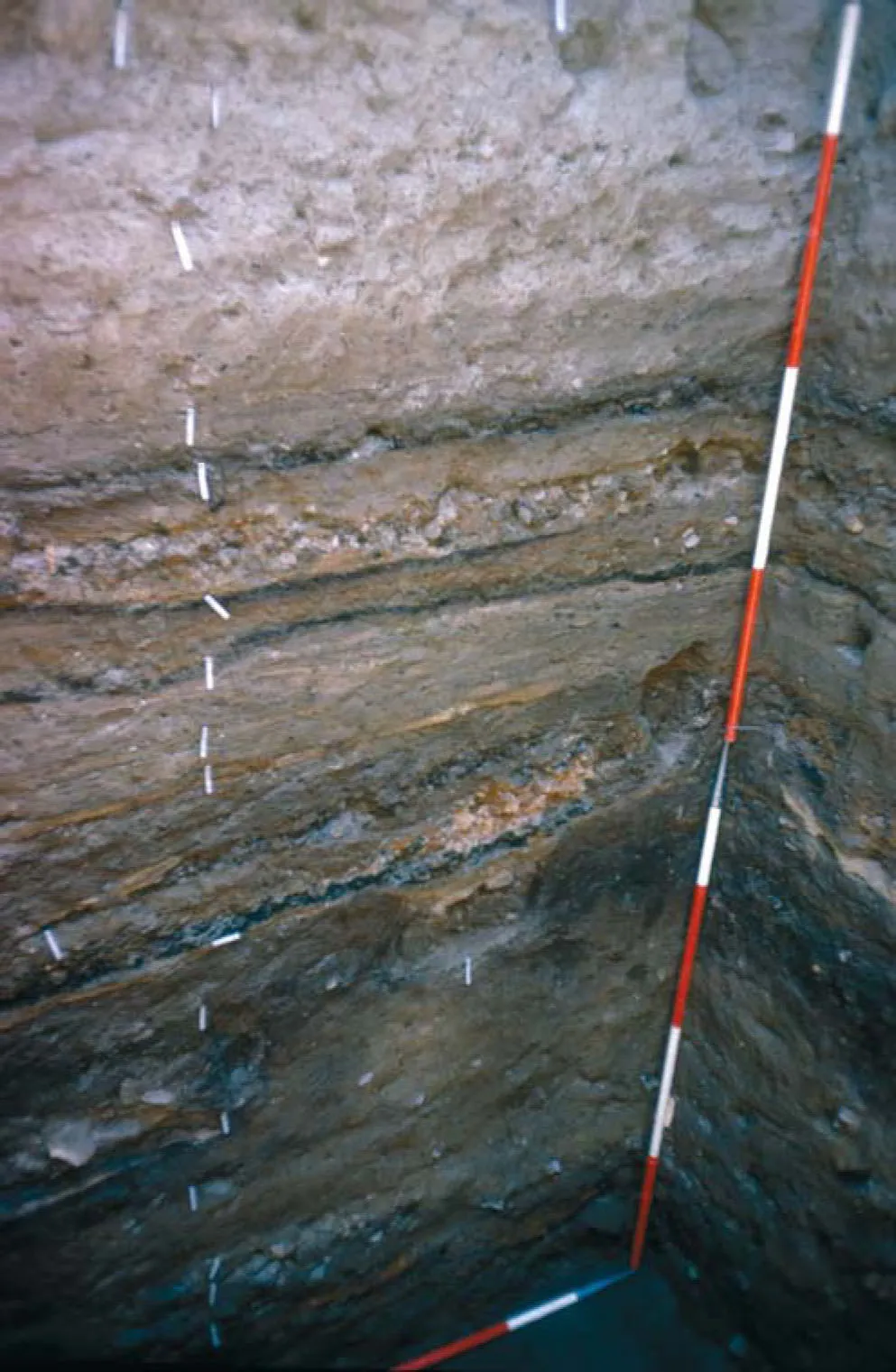

The length of the Neolithic sequence in the Balkans was admirably demonstrated by the great site of Karanovo in Bulgaria, excavated by V. Mikov and G. Georgiev (Fig. 1.1). The great stratigraphic sequence at Karanovo became a kind of template for the Balkans. It revealed with a powerful material reality that the Later Neolithic involved periods of extensive duration, exemplified and materialised in its deep stratigraphy.3

One of the first Neolithic sites in Greece to be dated over its long stratigraphic sequence by a series of radiocarbon determinations of well-stratified samples was Sitagroi in East Macedonia.4 From surface indications it was clear before excavation that its sequence contained strata with graphite-painted pottery related to that of the Gumelnitsa culture as seen at Karanovo VI. There were also Early Bronze Age dark-faced wares resembling those of Early Bronze Age Troy. It therefore offered the hope of resolving the problems of stratigraphic equivalence between the Aegean and the Balkans which the first radiocarbon dates had presented.5

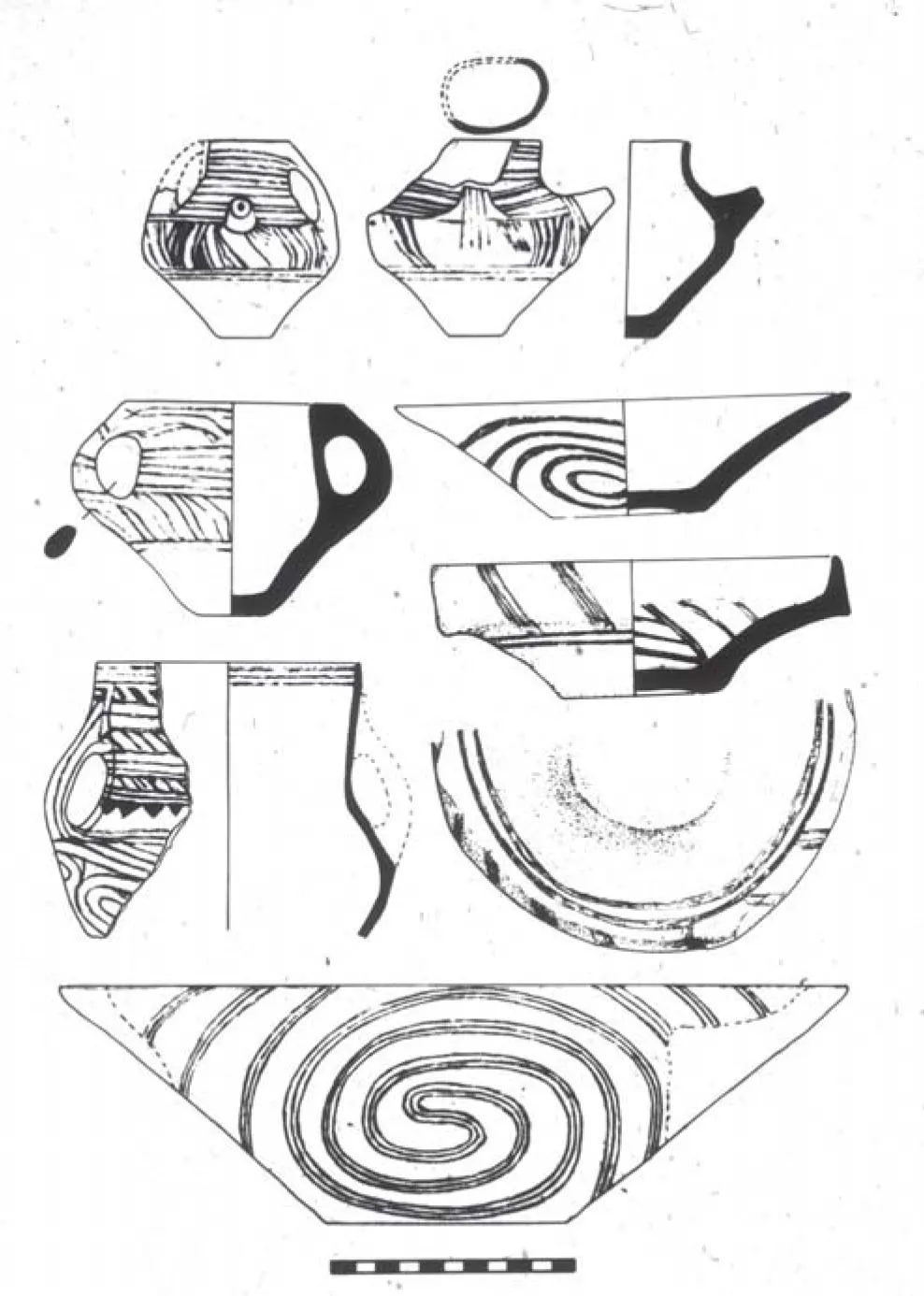

The deep section at Sitagroi opened in 1968 (Figs 1.2 and 1.3) confirmed for the Aegean what Karanovo had demonstrated for the Balkans: well before the Early Bronze Age of Sitagroi V, with its affinities to Troy I and II and to Karanovo VII and Ezero, there was the long Late Neolithic or Chalcolithic of Sitagroi phase III, corresponding to Karanovo phases V and VI and Gumelnitsa (Figs 1.4–6). Beneath these at Sitagroi was Sitagroi phase I with its dark-faced pottery relating to the Vesselinovo cultures seen at Karanovo III, followed by a stratum (Sitagroi II) with dark-on-light painted wares comparable to those of the Thessalian Middle and Late Neolithic. The pottery of Sitagroi was published in detail in 19866 and the corresponding radiocarbon chronology reviewed in 1971.7

Sitagroi phase IV had a dark faced ware with channelled decoration, related to the Baden culture, and phases Va and Vb related to the Trojan Early Bronze Age. Phase Va was that of the “Burnt House” at Sitagroi, and phase Vb had thickened rolled-rim bowls (Fig. 1.7) and one-handled cups (Fig. 1.8) related to those of Troy. The broad validity of the synchronisms seen at Sitagroi has since been demonstrated with greater precision by the abundant series of radiocarbon determinations from the excavations at the important site of Dikili-Tash,8 which is also located in the plain of Drama.

It was therefore possible in 1972 to suggest a culture sequence for the Later Neolithic of the Aegean9 where there was plenty of room on a calibrated radiocarbon chronology in the period after what had been termed the Late Neolithic or Chalcolithic or “Aeneolithic” (now occupying the 5th millennium BC in calendar years) for the newly invented “Final Neolithic,” placed from around 4100 BC to around 3200 BC (Fig. 1.9).

Figure 1.1. The stratigraphic section at Karanovo, photographed by the author in 1962.

A “missing millennium?”

When such a table was systematically set out, there was, in 1972, not much archaeological material available in some areas of the Aegean to place in the open spaces in the “chest of drawers” diagram which was thereby produced. There certainly appeared to be some gaps. The absence of any Neolithic at all on the Cycladic islands had already been rectified by the excavation of Saliagos near Antiparos.10 The Middle Neolithic Saliagos culture would soon be further and richly documented by the excavations at Ftelia on Mykonos11 and later by the work of F. Mavridis in the Cave of Antiparos.12 But the lacunae in the table led some scholars to speak of a gap, or even of a “missing millennium.”

Some sceptics even suggested that these lacunae might be an artefact of the radiocarbon dating and calibration process itself. For it is indeed the case that there are “kinks” in the radiocarbon calibration curve13 which may lead to some bunching. If successive samples, each separated by one century in calendar years, were subjected to radiocarbon dating, there would indeed be some bunching arising from the “kinks” (i.e. variations in slope) in the calibration curve. But similar problems have been examined in other areas, for instance in Neolithic Orkney.14 There similar effects can be observed,15 although not at precisely the time under discussion here in the Aegean, and not over as many centuries. So, although the effects of varying cosmic radiation on the atmospheric reservoir of radiocarbon should not be overlooked, they do not adequately explain the archaeological phenomenon before us.

Figure 1.2. The deep sounding of Trench ZA at Sitagroi in 1968 (scale in 50 cm units).

Local variations and interaction

In reality the supposed effects of the phenomenon of “absence” look very different as one moves from region to region in the Aegean. In the Cyclades, the discovery of the Saliagos and Kephala cultures in the 1960s had already established the reality of the Neolithic occupation of the islands. The discovery of Strofilas on Andros now transforms the picture,16 with its striking fortifications, which are clearly much older than those of Troy. The occurrence of the ring idol motif17 suggests a link dating back to the Balkan Chalcolithic and the Middle Neolithic of Thessaly. The pressure flaked obsidian arrowheads, characteristic of the Saliagos culture, support this chronological link. At the later end of the chronological scale there are ceramic affinities with the incised jars with vertical lugs of the Grotta-Pelos culture18 which suggest that the occupancy of Strofilas might last until the onset of the Cycladic Early Bronze Age.

Figure 1.3. Stratigraphic section of Trench ZA at Sitagroi.

Figure 1.4. Graphite-painted pottery from Phase III at Sitagroi.

Figure 1.5. Graphite-painted pottery from Phase III at Sitagroi

Figure 1.6. Black-on-red pottery from Phase III at Sitagroi.

Figure 1.7. Tubular lug handles from bowls of Phase Vb at Sitagroi.

Figure 1.8. One-handled cups from Phase Vb at Sitagroi.

Excavations in the Cave of Zas, Naxos,19 and more recently in the Cave of Antiparos20 could likewise be interpreted in terms of continuity. But occupation in these cave sites must always have been of an intermittent character, and alternative scenarios involving changing or successive populations can readily be formulated and can scarcely be refuted on the evidence the caves provide.

Figure 1.9. Culture sequence and absolute chronology for the Final Neolithic as reviewed in 1972 (after Renfrew 1972, 76).

In the East Aegean, the culture sequence at Emporio on Chios already gave suggestions of continuity from the Earlier Neolithic of Ayio Gala to the Early Bronze Age,21 although the re-examination of the sequence22 has to be taken into account. This remains one of the few sites in the Aegean for which a case for unbroken continuity over the 5th and 4th millennia...