![]()

1

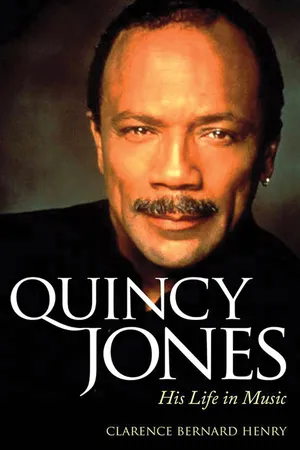

A RETROSPECTIVE OF QUINCY JONES

An American Music Icon

For more than six decades Quincy Jones has continually helped shape many styles of American music. To comprehend his global status, one needs only to refer to the popularity of works such as Michael Jackson’s Thriller (1982), the “We Are the World” collaboration (1985), or “Soul Bossa Nova” (1962), a composition later incorporated as the theme song for the movie, Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1997). With such accomplishments, it seems that Jones’s musical experiences and career warrants a study on many levels. This chapter presents a retrospective of the musical experiences, career, and artistic innovations of Jones and his contributions to American music.

Quincy Jones was born in Chicago, Illinois, on March 14, 1933. As a young child Jones experienced hard living on the South Side of Chicago, an area with a rich history of African American music and culture. For example, in 1893 Chicago hosted the World’s Columbian Exposition (World’s Fair) where ragtime as a popular music style and performances by Scott Joplin received broad public exposure. During the 1930s, Chicago was a major city of opportunity and part of a massive migratory movement of African Americans to northern areas of the United States from the Jim Crow South, seeking better economic opportunities. Also, similar to the New York City Harlem Renaissance in the 1930s and 1940s, Chicago was an important cultural center for African American expression in music and other artistic forms.

Chicago thrived with different sounds of popular music. The South Side was known as the “vice district” or as the “Levee.” It became the home for many African Americans and black-owned social clubs. Many of these clubs supported African American entertainers and fostered a sense of racial pride on the South Side. Many of the social clubs (cabarets and saloons) were referred to as black and tans because they catered to a mix African American and white clientele.1 In this setting some of the best musicians were major attractions. This include several New Orleans jazz musicians—Freddie Keppard, Kid (Edward) Ory, Joe King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Lillian Hardin, Earl Hines, and Jimmy Noone.

During the 1930s and 1940s Chicago’s South Side was also one of the major urban centers for the further development of the blues, particularly with a style that became referred to Chicago blues. Early blues artists such as Big Bill Broonzy, Tampa Red, Memphis Minnie, John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson, Big Joe Williams, Bukka White, Washboard Sam, and Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup greatly contributed to the Chicago blues tradition. But although many of these musicians had dominated the blues scene in Chicago, when Muddy Waters (McKinley Morganfield) (1915–1983) arrived from the Mississippi Delta area in early 1940s, the sound of Chicago blues was truly born. Waters who became known as “Father of Chicago Blues” and the “Godfather of the Blues,” first worked as a musician and became recognized on Chicago’s South Side especially with his innovative use of a sturdy electric guitar with an amplifier that could be played very loudly. This made an impression among many blues musicians in Chicago and in other areas.

In the mid-1940s, the South Side also became a significant haven for the development of urban gospel music, a tradition that was greatly influenced by the innovations of Thomas Andrew Dorsey (1899–1993), who became known as the “Father of African American gospel music.” Dorsey incorporated jazz, blues, and religious music into a rich urban gospel music texture that was nurtured in Chicago by musicians such as Mahalia Jackson, Sallie Martin, Roberta Martin, and many others.

Jones acquired an early indoctrination into jazz, blues, and gospel because of the constant and tangible musical presence on the South Side, where he was constantly exposed to the rich musical culture that he experienced in the city, at home (especially from his mother. who often sang religious songs), and in his local neighborhood as one of his female neighbors on a daily basis performed stride piano.2 Even at a young age Jones exhibited skills in musicianship. He was often drawn by his inner aesthetic emotions that were energized with the sounds of music in his neighborhood as being positive experiences that would affect his entire life. But it was in another city during the 1940s where his personal engagement with music would be fully realized.

Jones and his family were part of a second wave of migratory movement of African Americans to western regions of the United States, especially during the 1940s, when some African Americans relocated to the area to seek better economic and performing opportunities. Jones and his family relocated to the Seattle, Washington, area to pursue a better life. During this time he began to have a personal experience with music.

In Seattle Jones would be exposed to musical and cultural diversity similar to New Orleans, New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles. By the mid- to late 1940s Seattle had an established African American community as well as social clubs (jook joints) where territorial bands (traveling and touring bands from different cities) often performed.3 In the city there were several important neighborhoods such as Jackson Street from 1st to 14th Streets and Madison Street between 21st and 33rd. In these neighborhoods the soundscapes were comprised of an array bebop, blues, rhythm & blues, Dixieland, and classical. Also, located in several of these neighborhoods were popular social clubs such as Trianon Ballroom, Palomar Theater, and the Washington Social and Education Club. Musicians of the highest caliber were readily available in Seattle—Clark Terry, Billy Eckstine, Bobby Tucker, Sarah Vaughan, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie.

Jones’s personal experience with music began in 1945, when he was approximately eleven years old, in Sinclair Heights, an African American neighborhood in the Navy town of Bremerton close to Seattle. At a recreation center called the Armory, he and some neighborhood friends broke into the soda fountain area and found a freezer where lemon meringue pie and ice cream were stored. But for Jones, there was a much greater experience in that in the Armory he discovered a tiny stage in the room and on it was an old upright piano. As he tinkled on the keys he began to find a sense of peace.4 This experience changed the direction of his entire life—in essence the beginning of his personal engagement with music.

As time progressed, music became for Jones a form of expression, a way of knowing, and a skill in problem-solving and high-order comprehension. Since that time, music has always been something in his inner being that he could control but that also offered a type of freedom. Music became a type of communicative language where Jones could openly express himself artistically and creatively. When he played music his nightmares ended, his family problems disappeared, and he did not have to search for answers. This positive experience with music made Jones feel a sense of fullness and self-reliance.

In a pedagogical sense, Jones’s early experiences with music involved an integrative process of an eclectic curriculum. This involved a creative and continual use of community resources, social venues, mentor/teacher relationships, and observations and interactions with performing musicians. Jones’s early experiences also involved an active exploration of music in the city of Seattle, where over time he was able to musically develop a deep sense of inner hearing and memory. This also involved his constant in-depth focus of acquiring knowledge about the concepts and functions of music (e.g., harmony, structure, form, and style).

One early musical experience involved a local barber. As Jones wandered past the house of the barber in Sinclair Heights, a man named Eddie Lewis stepped out onto the front steps of his house holding a trumpet, blasted a few notes, and then stepped back inside. Jones was amazed that Lewis could play many notes on the trumpet only using three valves. After this, Jones had an opportunity to ask Lewis several questions about the intricacies of playing the trumpet.

Jones began to nurture his musical ability in a more formal setting at the racially integrated Robert A. Coontz Junior High School, where he sang in the choir and performed in the band. He became obsessed with the inner workings of the school band ensemble, musical instruments, and arrangements. He also studied many different musical instruments—drums, tuba, B-flat baritone horn, French horn, E-flat alto horn, Sousaphone, piano, violin, and clarinet—but these were not suited for him.

As a member of the band, Jones possessed an inquisitive mind about the fundamentals of music, style, and form. In this experience with his school band Jones described that, “I was curious about orchestration [writing music]. I [often wondered] how could people [in the band] play together and not be playing the same notes? But I got totally obsessed with playing. I would stay in the band room all day and play [every musical instrument].”5 But ultimately, Jones began to concentrate on the trumpet as his principal instrument. His father was supportive and provided Jones with his first trumpet.

In addition to his interest in musical instruments, Jones also performed as a singer in a gospel quartet called the Challengers under the direction of a local music teacher named Joseph Powe. In his home library Powe collected books on arranging and film scoring. Jones took the opportunity to study many of these scores and arrangements. This initial inquiry allowed Jones to concentrate more on the technical aspects of arranging music and learn the ranges and notation of certain instruments (e.g., B-flat trumpet) on a music score.

In his early experience Jones once described that, “I used to babysit for Powe. I’d look at his Glenn Miller arranging books and it was just like walking into fantasyland, just to be able to look at those things with the trombones and how they worked. How you put the [saxophones] and trombones and stuff together. I was just hooked on it. I must have been about thirteen. It took over my life.”6

Jazz trumpeter Clark Terry served as one of Jones’s early important mentor/teachers. Terry performed with many bands over the course of his long career, including those of Charlie Barnet, Count Basie (both big bands and small ensembles), and Duke Ellington.7 He greatly influenced modern jazz and invented a unique style of trumpet playing that bridged the gap between the swing era of the 1930s and approaches to the bebop style of 1940s by musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie. Clark Terry constantly displayed an effortless command on the trumpet. He had an ability to play fast and intricate passages and elaborate melodic lines.

In 1947 when Jones was thirteen years old, he constantly sought music lessons from Clark Terry, who would often travel to Seattle to perform gigs. On one occasion when Terry was performing at the Palomar Theater in Seattle, Jones approached Terry and introduced himself and mentioned that he was in the process of learning how to play the trumpet and write music. When Terry was in town, Jones would often arrive at Terry’s place of residence early in the morning for lessons. Jones and Terry would work for hours and when the sessions ended Jones would attend school. The lessons were beneficial to Jones’s future as a musician. Jones noted that, “[Clark Terry] taught me and talked to me and gave me the confidence to get out there and see what I could do on my own.”8 This experience with Clark Terry greatly influenced Jones’s continued growth and development in music.

In addition to his work with Clark Terry, Jones attended James A. Garfield High School, where he had opportunities to interact with students of different ethnic and socio-cultural backgrounds and musical interests. By this time it was undeniable that Jones possessed an artistic gift and a distinct ability to hear, perform, and respond to harmony.

Jones and his friend Charles Taylor performed in the Garfield High School concert band under the direction of Parker Cook, a teacher and musician who was very supportive of Jones’s interests in composing and arranging. Jones and Taylor both also studied with a musician named Frank Waldron.

In 1948 Jones was a member of the Garfield High School military band. Many African American and white musicians of the band shared a deep friendship and camaraderie that influenced Jones’s ideologies of cultural diversity. Among the band members for this particular ensemble was Jones’s white friend Norm Calvo, who stated that “we were at least 10 years ahead of the curve of camaraderie when it came to race, everybody just sort of blended.”9 No one found it unusual when Jones and other African American members of the band walked to Calvo’s house after school to jam in Calvo’s parents’ music room.

As early as 1947 Jones had already established his talent as a vibrant trumpet player outside of high school by performing in a semi-professional band organized by his school friend, Charles Taylor. Some of the band members included: Oscar Holden Jr. (tenor saxophone), Grace Holden (piano), Billy Johnson (bass), Major Pigford (trombone), Waymond Jones (temporary drummer), Harold Redmond (drummer), and Buddy Catlett (alto saxophone). This band was later reorganized and incorporated as the Bumps Blackwell Junior Band. “Bumps,” whose real name was Robert Blackwell, played the vibraphone and served as the bandleader for the group.10

The Bumps Blackwell Junior Band consisted of Billy Johnson (bass), Harold Redmond (drums), Charles Taylor (tenor saxophone), Buddy Catlett (alto saxophone, but he later became known for playing bass), Quincy Jones (trumpet), Bumps Blackwell (vibraphone), Major Pigford (trombone), and Tommy Adams (vocalist and sometimes drums). Blackwell also added to the group two female performers: August Mae, a tap dancer, and vocalist Ernestine Anderson, who later became a famous jazz singer with talents often regarded similar to that of Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan.

Performing with these early bands was important in Jones’s musical development, helping shape his aspirations of pursuing music as a career and exposing him to different types of collaborative projects with talented jazz musicians in Seattle and other parts of the United States. For example, the Bumps Blackwell Junior Band performed as a backup for Billie Holiday and Billy Eckstine when they performed in the Seattle area.

The Bumps Blackwell Junior Band in many ways prepared Jones to be competitive with more professional ensembles. When he became a member of the Lionel Hampton Orchestra a few years later, he understood firsthand the inner workings of the performance stage, big band ensemble format, instrumentation, audience and performer response, and jazz and rhythm & blues repertoire.

Jazz bassist Buddy Catlett, one of the original members of the Bumps Blackwell Junior Band who himself became a legendary musician, has pointed out that he personally witnessed that Quincy Jones possessed an ability to compose and arrange at a very young age. Catlett witnessed firsthand that even before Jones became a member of the Lionel Hampton Orchestra, he had progressed to mastering his composing and arranging skills. Catlett pointed out that as a teenager, “during this period with Bumps [Jones] wrote most of the book [arrangements]. He was only 15. … He was serious about everything. He really took his time to figure out what he was doing.”11

In addition to performing popular music, Jones and other members of the Bumps Blackwell Junior Band were also proficient in performing military marches, a skill they learned as members of a military regiment located at Camp Murray in the Seattle area. They were officially sworn in the African American Washington National Guard 41st Infantry Division Band. The young men were provided with uniforms and new musical instruments and they were required to participate in drills at the Armory in Seattle. For a time, Jones was an official bugler for the regiment. During several months each summer the members of this regiment were also assigned active duty with the army at Camp Murray.

As a young musician Jones developed a strong-willed personality and tenacity for meeting, performing, and dialoging with established musicians, a skill that contributed to his success in the popular music industry. In his mid-teenage years he had already become personally acquainted with Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Woody Herman, and Milt Hinton, always seeking music lessons. One of his most poignant experiences in Seattle was observing an open rehearsal of a professional symphonic orchestra under conductor Arturo Toscanini (1867–1957) and Harry Lookofsky (violinist and concertmaster). This experience contributed another dimension of music by opening his insights into the Western class...