eBook - ePub

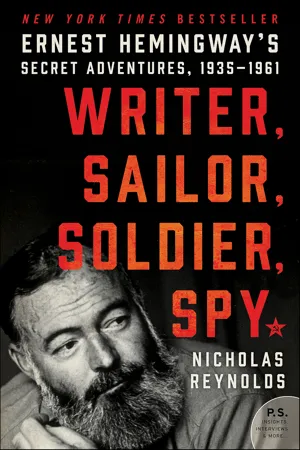

Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy

Ernest Hemingway's Secret Adventures, 1935–1961

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A

New York Times–bestseller from an intelligence insider reveals the "fascinating new research" revealing Hemingway's hidden life in espionage (

New York Review of Books).

A riveting epic, Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy reveals for the first time Ernest Hemingway's secret adventures in espionage and intelligence.

While he was the historian at the CIA Museum, Nicholas Reynolds, former American intelligence officer and U.S. Marine colonel, uncovered clues suggesting the Nobel Prize-winning novelist was deeply involved in spycraft. Now Reynolds's captivating narrative "looks among the shadows and finds a Hemingway not seen before" ( London Review of Books), revealing for the first time the whole story of this hidden side of Hemingway's life: his troubling recruitment by Soviet spies to work with the NKVD, the forerunner to the KGB, followed in short order by a complex set of relationships with American agencies.

As he examines the links between Hemingway's work as an operative and as an author, Reynolds reveals how Hemingway's secret adventures influenced his literary output and contributed to the writer's block and mental decline that plagued him during the postwar years. Reynolds also illuminates how those same experiences played a role in some of Hemingway's greatest works, including For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea, while also adding to the burden that he carried at the end of his life and perhaps contributing to his suicide.

A literary biography with the soul of an espionage thriller, Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy is essential to our understanding of one of America's most legendary authors.

"Important." — Wall Street Journal

A riveting epic, Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy reveals for the first time Ernest Hemingway's secret adventures in espionage and intelligence.

While he was the historian at the CIA Museum, Nicholas Reynolds, former American intelligence officer and U.S. Marine colonel, uncovered clues suggesting the Nobel Prize-winning novelist was deeply involved in spycraft. Now Reynolds's captivating narrative "looks among the shadows and finds a Hemingway not seen before" ( London Review of Books), revealing for the first time the whole story of this hidden side of Hemingway's life: his troubling recruitment by Soviet spies to work with the NKVD, the forerunner to the KGB, followed in short order by a complex set of relationships with American agencies.

As he examines the links between Hemingway's work as an operative and as an author, Reynolds reveals how Hemingway's secret adventures influenced his literary output and contributed to the writer's block and mental decline that plagued him during the postwar years. Reynolds also illuminates how those same experiences played a role in some of Hemingway's greatest works, including For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea, while also adding to the burden that he carried at the end of his life and perhaps contributing to his suicide.

A literary biography with the soul of an espionage thriller, Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy is essential to our understanding of one of America's most legendary authors.

"Important." — Wall Street Journal

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Awakening

When the Sea Turned the Land Inside Out

Hemingway was not there just to observe. On September 4, 1935, he piloted his new cabin cruiser Pilar some seventy-five miles northeast from Key West to the Upper Keys to join in the recovery effort. Determined to do what he could to help the survivors of one of the most powerful hurricanes in American history, he had stocked Pilar with food, water, and the kind of supplies that made life outdoors a little more bearable. But there was hardly anyone to help. He had not witnessed a scene like this since serving on the front lines in Italy in World War I. On Labor Day the storm had torn through the narrow, low-lying islands and wreaked as much havoc as a days-long artillery barrage. Many of the biggest trees, Jamaican dogwood and mahogany, had been uprooted and lay on their sides. Only a handful of sturdy buildings were still standing, the rest now just piles of wood. Near the small post office at Islamorada, the train sent to evacuate relief workers had been blown off the rails, its cars scattered at crazy angles. Worst of all was finding the dead, their bodies bloated in the 80-degree heat of the late summer day. Many of them were floating in the water, which was still murky from the fifteen-foot storm surge. It was hard to miss the clump of dead men by a wooden dock, where they had lashed themselves to a piling to keep from being swept away. Two women were cradled in the branches of a mangrove tree that had survived the high water and the wind—had the victims tried to save themselves by climbing? Or did the waves toss them into their gruesome aerie? That did not make much difference now. The only way the great writer could help the dead was to write about them, to tell the world how it happened and who was to blame for the tragedy. He decided to bear witness in a way that would change his life.

By 1935, the year of the great hurricane, Hemingway had climbed to the top of his profession. Born just before the turn of the century, this ambitious young man from Oak Park, Illinois, had started a revolution in literature while still in his twenties. His two bestsellers, The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms, reflected how much he had lived in his first three decades: wounded veteran by nineteen, then foreign correspondent for the Toronto Daily Star and member of the Paris branch of the “Lost Generation” of legendarily talented writers.

The Nobel Prize for Literature that Hemingway later received ably explains the appeal of his work: his writing “honestly and undauntedly” reproduced “the hard countenance of the age” with a trademark combination of simplicity and precision. When he wrote, he was the soul of brevity, telling compelling stories in spare prose that spoke to millions of readers. His central theme was personal courage: he displayed “a natural admiration for every individual who fights the good fight in a world . . . overshadowed by violence and death.”1

Hemingway was so successful that he was now on his way to becoming a touchstone for every American writer, and a role model for not a few American individualists. They were reading Hemingway, quoting him, copying his behavior, and seeking his advice. While his voice was uniquely American, he was also recognized as one of the leading novelists in the world. He had only a handful of competitors. His fame had even spread to the Soviet Union, where literature was meant to serve politics. Increasingly, Soviet writers were not at liberty to tell the truth about the world as they saw it and instead had to cater to the government. That did not make much difference to the mostly apolitical Hemingway. But he did enjoy the fact that more and more Soviets were reading his works.

On August 19, 1935, at a time when American literary critics had made him feel underappreciated at home, Hemingway received a package from Moscow containing a copy of his selected stories translated into Russian. It was posted from a prominent young translator and literary figure named Ivan Kashkin, who had done more to promote Hemingway’s work in the USSR than anyone else, at first among fellow writers and then with other readers, including a few members of the ruling elite.2 Hemingway was happy to see the Russian editions and, “[h]ungry for compassion and empathy,” eager to read an enclosed essay that Kashkin had written in praise of the American writer.3 In the accompanying letter (to “Dear Sir, or Mr. Hemingway or maybe Dear Comrade”), Kashkin told Hemingway how much Soviet readers welcomed his work, almost uncritically: “[t]here is in our country no idle gaping at your brilliant and sensational achievements, no grin at your limitations.”4 Without delay Hemingway wrote to thank Kashkin and tell him what “a pleasure [it was] to have somebody know what you are writing about”—so unlike the usual critics in New York.5 This was the first of many long, remarkably frank letters to the man he would long value as critic and translator.6

Hemingway wanted to make sure Kashkin understood that while he was happy to have Soviet readers, he was not going to become a communist, or even a communist sympathizer. The successful young writer would maintain his independence despite pressure to move to the left. He explained to Kashkin in a letter that his friends and critics had told him he would wind up friendless if he did not write like a Marxist. But he did not care. “A writer,” he continued, “is like a Gypsy” who “owes no allegiance to any government” and “will never like the government he lives under.” It was better for government to be small; big government was necessarily “unjust.”7

No matter what he claimed, readers on the left began to find traces of class consciousness in Hemingway’s writing when he wrote about the fecklessness of American politicians, or how the rich in America ignored the plight of the poor. Some critics pointed to his short story “One Trip Across,” about a boatman forced by the failing economy to turn to crime; others, amazingly, cited a few remarks he made about conditions at home in America in his book The Green Hills of Africa, which was actually a travelogue about the rich man’s sport of big game hunting.8

The story that Hemingway would write for New Masses would surprise more than one left-leaning American and focus Soviet attention on him. Edited by American leftists and communists, this Marxist literary review fell just short of being an official organ of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA). When New Masses first appeared in 1926, Time magazine characterized it as “a smoky vessel, ungainly but powerful, with daubs of red on her lunging bows and red marks here and there on her somewhat disorderly running gear.”9

That disorder did not matter to a variety of writers who ranged from the world famous, like George Bernard Shaw and Maxim Gorky, to minor lights known only on the left, all of whom wanted their work published. Some of that work was political; much of it was not. Hemingway submitted articles on subjects as diverse as bullfighting and death in winter at a snowbound chalet in the Alps. He felt free to angrily denounce the editors after they published a scathing review of his novella Torrents of Spring. They only were revolutionaries, he wrote his old friend the poet Ezra Pound, because they hoped that a new order would see them as “men of talent.”10 The editors lashed back that Hemingway was too focused on the individual and did not understand the powerful economic forces determining the course of American history.

Those forces made themselves felt in 1929. That year the stock market crash led to a deep depression that challenged every assumption about the American dream. The engine of capitalism, Wall Street, had stalled, and could no longer move the economy. Something like one-fourth of the workforce was unemployed. An estimated two million men took to the rails, hopping on to freight trains and roaming the country in search of work. Millions more went hungry. Once-prominent businessmen stood on street corners selling pencils or apples, and then lined up with the unemployed at soup kitchens. The nation’s formerly prosperous farms did no better. The cities could not afford to buy as much meat and produce, and the Depression spread through the farmlands. A prolonged drought in the Great Plains made things worse; acre upon acre of farmland literally blew away, creating a vast dust bowl.

After 1929, New Masses moved still further to the left. The editors decided to descend “into the stormy arena where the day’s battles were raging,” and to send reporters “to the surging picket lines, . . . the worried farm sides, [and] the smoldering South.”11 The idea was to capture, firsthand, the many kinds of suffering caused by the country’s near-perfect economic and environmental storm. The resulting stories would attract readers who were now willing to take a hard look at the shortcomings of capitalism.

From afar, the Soviet Union seemed to offer a solution. The Soviets talked about a future where no one would be unemployed or hungry. It was a beguiling vision of a just, classless society. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy were, it seemed, made to order as counterweights to the Soviet Union. Hitler’s speeches set the tone for Germany. Gesturing forcefully, with closed fists, he would build to an angry crescendo, blaming the Jews and the communists for the crisis that gripped Germany as badly as the rest of the world. His was another way out of the Depression: silence your enemies, mobilize for war, take what you need from your enemies. With this approach, Hitler and his fellow dictator Mussolini drove many American artists into the arms of the left, much further than they might otherwise have gone.12

Even before the Depression hit, Hemingway had moved to Key West with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer. It was a place where they could start a family and where the robust, handsome sportsman—six feet tall, solidly muscled, with a full head of dark hair and dark eyes that commanded attention—could still live a halfway rugged outdoor life, or at least dress as if he were living that way, barefoot, in a plain shirt, usually only half-buttoned, and shorts cinched up with a piece of rope.

The southernmost tip of the Lower 48, Key West is nearly the last of a chain of small islands that protrude into the Gulf of Mexico from Florida. In 1928, it was a poor man’s tropical paradise, reachable from the mainland only by rail or boat. Many of the streets were not paved; many of the buildings had no plumbing or electricity. The closest thing to a grocery store was the small warehouse that sold necessities.

The beach was never far, the water always warm and clear. Even at a depth of fifteen feet the white sand at the bottom seemed close enough to touch. Fish of many kinds hovered above the sand, easy prey for locals. In deeper waters the fishing was even better. Fishermen sold or bartered the catch of the day to their neighbors, who rounded out their meals with rice and beans from a warehouse and fruit from their gardens. After dinner, anyone could sit on the town pier and watch the sun set over the ocean, then go to a rough-hewn bar first called the Blind Pig, then the Silver Slipper, and finally Sloppy Joe’s. Whatever its name, it was a place of “shabby discomfort, good friends, gambling, fifteen-cent whiskey, and ten-cent . . . gin” where the concrete floor was always wet from melting ice.13

Hemingway first heard about Key West from fellow novelist John Dos Passos, an intellectual from Baltimore—tall, shy, balding, more thoughtful than passionate, not unlike a professor. Still, he loved the outdoors, if not in quite the same way as the great fisherman and hunter Hemingway. Dos Passos had come upon the place while hiking down the Keys in 1924 and told Hemingway about his find in a letter. Hemingway came to visit and he too was smitten, eventually settling in a solid, two-story limestone house on Whitehead Street. Built in 1851, it looked like the kind of place a riverboat captain would put up in New Orleans, with its high wraparound porch, ornate grillwork, and wooden storm shutters usually painted green.

By 1930, the island city was suffering from the Depression. By 1934, Key West was literally bankrupt, unable to collect enough taxes to pay its bills. The Florida branch of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) stepped in and took over.14 Part of the island’s charm was that the mainland was far away; now, preempting the local government, a national agency was stepping in to save the key from itself. Dos Passos did not think much of the results. Something he called “relief racketeering” was turning “a town of independent fishermen and bootleggers” into “a poor farm.”15 Hemingway agreed. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the president’s way out of the Depression, was like “some sort of YMCA show” run by “starry-eyed bastards.” From Hemingway’s worldview, which placed a premium...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Cast of Characters

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Awakening: When the Sea Turned the Land Inside Out

- Chapter 2: The Writer and the Commissar: Going to War in Spain

- Chapter 3: Returning to Spain: To Stay the Course

- Chapter 4: The Bell Tolls for the Republic: Hemingway Bears Witness

- Chapter 5: The Secret File: The NKVD Plays its Hand

- Chapter 6: To Spy or Not to Spy: China and the Strain of War

- Chapter 7: The Crook Factory: A Secret War on Land

- Chapter 8: Pilar and the War at Sea: A Secret Agent of My Government

- Chapter 9: On to Paris: Brave as a Saladang

- Chapter 10: At the Front: The Last Months of the Great War Against Fascism

- Chapter 11: “The Creeps”: Not War, Not Peace

- Chapter 12: The Cold War: No More Brave Words

- Chapter 13: No Room to Maneuver: The Mature Antifascist in Cuba and Ketchum

- Epilogue: Calculating the Hidden Costs

- Sources

- Acknowledgments

- Permissions

- Endnotes

- Index

- P.S. Insights, Interviews & More . . .*

- Praise

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy by Nicholas E. Reynolds in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.