eBook - ePub

The Chasm Companion

A Fieldbook to Crossing the Chasm and Inside the Tornado

This is a test

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In The Chasm Companion, The Chasm Group's Paul Wiefels presents readers with a new analysis of the ideas introduced in bestselling author Geoffrey Moore's classic books, Crossing the Chasm and Inside the Tornado, and focuses on how to translate these ideas into actionable strategy and implementation programs. This step-by-step fieldbook is organized around three major concepts: how high-tech markets develop, creating market development strategy, and executing go-to-market programs based on the strategy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Chasm Companion by Paul Wiefels in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Marketing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

How High-Tech Markets Develop

This section reviews the key principles governing each inflection point on the Technology Adoption Life Cycle and explores some key mistakes or missteps that organizations make at each point.

1

Back to the Basics

The ideas and concepts outlined in this book are built in part upon theories of high-tech market development first discussed in Crossing the Chasm, originally published in 1991, and Inside the Tornado, published in 1995. My partner, Geoffrey Moore, authored both books, and in them he defined and refined a vocabulary and framework for understanding how and why high-technology markets develop for discontinuous innovations, and why these markets evolve as they do. Over the years we have used our experience in consulting with technology-based organizations, both large and small, to hone these concepts further, adding to an ever widening body of work. We have added, modified, borrowed, and discarded ideas based on these experiences. And we are grateful that many of our clients are willing co-conspirators.

Since continuous innovations still account for a significant portion of modern economies, it is hardly surprising that much of the language of business and the specifics of modern marketing theory and practice continue to reflect this fact. Yet, the fastest-growing sectors of these same modern economies are now driven by discontinuities—disruptive technologies that force changes in both strategy and behavior that are often counterintuitive to both buyer and seller. Thus, a knowledge and practice gap exists, a condition that is completely understandable when you compare the number of patents issued between 1900 and 1970 with the number issued since 1970. It is exactly this gap that high-tech organizations face every day. They must make sense of developing markets and business practices where, to paraphrase a line from the Star Trek TV series, “no one has gone before.”

Since the basic function of business strategy is to create wealth for shareholders, employees, and society, we start our investigation with some basic principles and observations—some long held, others gleaned from the technology market meltdown recently witnessed.

We begin by trying to make more sense of what has transpired during the recent past.

One way to describe the excessive valuations in the technology sector in the run-up to the year 2000, particularly those surrounding the Internet, is that investors fell under the spell of category power. Historically, when whole new paradigms—underpinned by discontinuous innovations—have entered the sector, they have driven massive transfers of valuation, much of which accumulates in the market-leading companies. Internet investors anticipated this trend and bid up the stocks of any company with a good story about how it would ride this latest hypergrowth category to wealth and power.

We are reminded of the old proverb “Many are called, but few are chosen.” Now we want to examine the results of a few quarters of competitive performance before bidding up a stock. Instead of jumping on the bandwagon of companies declaring victory based on a declared strategy of preemptive market leadership, the markets wait to see if victory (a) has been achieved, (b) can be sustained, and (c) is worth anything once both conditions are satisfied.

The implications for management teams are straightforward enough. Quit fooling around (or fooling yourself ) with strategy or business-model experiments and go make some money. Do this by focusing on your core business. Do it by selling something for cash to customers who pay their bills. Launch a new and exciting product or service. Penetrate a new market with a valuable value proposition. And when competition appears, show that you can hold it at bay not through discounts but through differentiated value.

SHOW ME THE VALUE

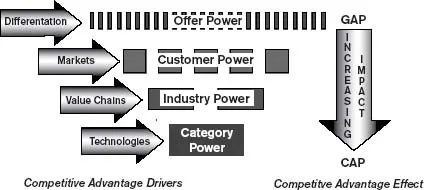

Those of you who have read our most recent books, The Gorilla Game and Living on the Fault Line, may recall the concepts of Competitive Advantage Gap (GAP) and Competitive Advantage Period (CAP). GAP is the value of your company’s differentiated offerings when compared with those of your direct competitors. CAP is the length of time that investors anticipate you can sustain that differentiated advantage. In the investment climate prior to March 2000, all the emphasis was on catching the next technology wave. This represented a focus (some would argue an obsession) on CAP, manifested as a fear that the current advantages enjoyed by the status quo would be summarily wiped out by an emerging new category—the now legendary New Economy. While understanding CAP potential remains important, nowadays the emphasis is on demonstrating results in the present rather than in the future. We live now in a world dominated by GAP, the power to win business through differentiated offerings in viable, demonstrable, and compelling categories. Our first return to the basics should be dominated by that thought.

The implications of this for management are far-reaching. In surveying where to invest scarce resources for competitive advantage, The Chasm Group uses a Competitive Advantage Hierarchy model that isolates four general domains where companies can focus attention. They are:

- differentiated offerings—denoted as offer power

- market segment domination—denoted as customer power

- value chain leadership—denoted as industry power

- new category participation—denoted as category power

Competitive Advantage Heirarchy

Category and industry power, i.e., the strength and importance of the value chain you operate within, have a greater effect on CAP and the long term; while your customer power, i.e., the number and type of customers that you have captured and the offers you have fielded to capture them, have more impact short-term on GAP. Investors currently feeling burned by new business models are turning away from new category participation, value chain domination, and other heady visions of the future. “Show us some differentiated offerings that make money today,” they demand.

SHOW ME THE MONEY

To be sure, value chain domination holds forth the promise of immense competitive advantage sustainable over long periods of time. It has long been the driving force behind the valuations of such behemoths as Cisco, Intel, Microsoft, and SAP. No one doubts that it is a great prize and worth much sacrifice to gain. But investors have learned that as a sustainable outcome for any particular company, it is improbable. And so they are prepared to search for other safe harbors as they seek more reliable returns from their increasingly scarce capital.

When the focus was almost exclusively on value chain domination, investors eagerly sought news of emerging partnership announcements that would signal value chain formation and provide clues as to which companies were accumulating the most marketplace power. Both Amazon and Yahoo! validated their investors’ expectations by demonstrating value chain power recruiting numerous partners in excess of what their direct competitors could demonstrate. But such auspicious beginnings would later temper investor optimism when such value chains, once formed, proved nowhere near as valuable as advertised, at least not in the short term. As companies, notably Amazon, called again for more patience and capital in order to demonstrate their true values, investors decided they had no more of either. In the current climate they are simply making that most basic of all requests—Show us the money! Partners do not pay money; customers do. Show us the customers, what you plan to offer them, and how you intend to keep them.

In this context, customers with large budgets to spend are preferable to those of more modest means, which translates into higher valuations going to companies with large-enterprise customers than to those focused on small-business or fickle consumer markets. But in all cases there is a focus on liquidity, on the ability to generate initial order and repeat business such that investments in fixed costs and customer acquisition can be paid down. Thus the need to quickly understand the dynamics of market development—the shifts in focus that now seem almost preordained—and do something about them, not because of Internet time per se, but because that is what investors are looking for, and what they want to see now.

In 1999, the toughest hire in Silicon Valley was a great vice president of business development. This rare bird combined the savvy of a salesperson with the power-brokering skills of a lobbyist and was sent out into the world to spin a coalition of partners into a value chain. Every key announcement was greeted with an escalation in stock price. As stock currency grew cheap and plentiful, acquisitions became the preferred substitute for organic growth, further distracting investors from the dramatic outflow of cash from core business operations. Strategic alliances became the focus, the buzzword du jour.

In demand now is someone who can recruit and lead a direct-sales force selling into enterprise customers offerings that have an average selling price into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, with large deals going over $1 million, and even higher in special circumstances. The call is for someone who has closed a quarter, has closed dozens of quarters in fact, making quota. Such rainmakers are not to be found among any recent business school graduates, or in the outflow of people from dead or dying dot-coms. Instead, the sales organizations at big systems houses like Hewlett-Packard, Sun, and IBM, along with large consultancies and integrators like Accenture and EDS, are the breeding grounds in which recruiters will now be trawling.

SHOW ME THE MONEY NOW

In the era just past, most companies, notably the dot-coms, sought to validate their valuations by treating the lifetime value of a customer as their primary asset—an asset that could be booked like any other. This is not a bad idea per se, but it is subject to interpretation and abuse. What lessons can we learn?

- “Eyeballs” are not a reliable indicator of, or proxy for, customers. Orders may be. The real issue is not trial, but repeat orders. Will or can customers switch from one vendor to another?

- Any projections of future returns from current customers should include a churn rate validated by actual customer behavior. Total available market statistics are far less relevant than those representing the total addressable market—the relevant part of the market, which can be appealed to over and over again and will behave in the desired way.

- Customer-acquisition costs are paid in present dollars; lifetime value is paid out in increasingly future dollars. Such future returns must exceed those gained by simply putting the same money in government-backed bonds.

- “Irrational exuberance” has now been wrung out of the public markets, and decidedly so. We find ourselves getting back to the future, and realize that the tide will turn decidedly bullish once again—and not soon enough for most of us.

- Our industry will emerge different in the next up-cycle. Seeking to understand those differences begins now.

But maybe the biggest lesson was recognizing the sheer magnitude of the capital needed to achieve the lofty lifetime goals investors and management were pursuing. In all of these models it takes a long time and a lot of money just to get to breakeven, and investors are now seeing that the model works only if customers can be persuaded to supply part of the needed funding through advance funding of their own, i.e., buying and continuing to buy. The mission we now embark on is to understand how to get customers to do exactly that.

2

The Basis for Strategy Decisions

High-tech companies, whether they know it or not (and most of them do), base their most fundamental strategic decisions on a model that is now older than most high-tech companies themselves. That’s right. Apple, Intel, Microsoft, Cisco, Dell, Hewlett-Packard, and literally thousands of companies besides are devotees, acknowledged or not, of a model that was first postulated in the late 1930s and advanced in the 1950s by researchers at Harvard University who were interested in how people—indeed, communities of people—consider and adopt discontinuous innovations. We call this model the Technology Adoption Life Cycle, or TALC for short. Because this model is seemingly so accurate and, as a result, so pervasive within high technology, it is the foundation for this book, as it has been the foundation for two previous books authored by my colleague Geoffrey Moore. The life cycle model is the fundamental basis for how we at The Chasm Group think about developing and executing strategy—specifically what we will call market development strategy. While the following may be old news to some, it is nonetheless useful here to review some basics.

THE NATURE OF DISCONTINUOUS INNOVATIONS

To start, let us consider the nature of a discontinuous innovation. What is it? How does it come into being? How should we react to it?

What it is, is typically obvious to everyone. It’s the automobile or the telephone of the early 1900s. It’s the machine gun or battle tank of World War I, or the atomic bomb of World War II and the Cold War. It’s the minicomputer of the 1960s, and the microprocessor and personal computer of the ’70s and early ’80s. It’s the relational database and distributed computing. It’s the genetic sequencer. It’s the electric car. It’s the Internet and the dot-com. As of this writing, it’s application servers which underpin other e-business infrastructure applications.

What attributes do these very different innovations have in common?

First, they all represent significant, even radical, departures from the status quo. Second, these innovations were not merely new or different from what preceded them. They reshaped (and are reshaping) fundamentally the field of human endeavor—whether it is communications, transportation, warfare, information processing, treatment of disease, or how we buy and sell things. These innovations do not alter an otherwise level playing field. They crater and scorch it. Suffice it to say that discontinuous innovations—and the benefits they promise—often render what preceded them irrelevant and obsolete. Do you remember when you last bought a typewriter?

If a discontinuous innovation changes everything, correspondingly, a continuous innovation changes very little, much to the relief and benefit of the buyer and user of the continuous innovation. Why? Simply for the reason that the continuous innovation requires little or no behavioral change on the part of anybody. Users, in particular, feel virtually nothing except the specific and typically modest benefit associated with the so-called innovation. This means that they are built upon the infrastructure and standards already in place at the time. Think of a continuous innovation as the “green bleaching crystals” in your laundry detergent. Why are they there? The ad...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One

- Part Two

- Part Three

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- Worksheets

- Searchable Terms

- About the Author

- Copyright

- About the Publisher