eBook - ePub

Major Trends in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics 2

This is a test

- 470 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Major Trends in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics 2

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In the three volumes of Major Trends in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, the editors guide the reader through a well-selected compendium of works, presenting a fresh look at contemporary linguistics. Aimed at specialists or anyone interested in languages, this publication deals with both theoretical issues and applied linguistics, looking closely at discourse analysis, gender and lexicography, language acquisition and language disorders.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Major Trends in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics 2 by Nikolaos Lavidas, Thomaï Alexiou, Areti Maria Sougari, Nikolaos Lavidas, Thomaï Alexiou, Areti Maria Sougari in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Language Acquisition

“Automatically Arises the Question Whether...”: A Corpus Study of Postverbal Subjects in L2 English1

Eleni Agathopoulou

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

Abstract

The current study offers a novel set of data on phenomena regarding SV/VS in L2 English. We explored structures with unergative and unaccusative predicates in the corpus of Greek learners of English (GRICLE) and in comparable native English corpora. Results showed that for both the learners and the natives word order is conditioned by properties (a) of the lexicon-syntax interface, i.e. VS appears only with unaccusatives and never with unergatives and (b) of the syntax-discourse interface, i.e. postverbal S in unaccusatives expresses focus rather than topic. Moreover word order is conditioned by properties of the syntax-phonology interface, in that postverbal subjects tend to be phonologically heavy, albeit only in the learner data. Our results almost replicate results in previous corpus-based research.

1. Introduction

In generative second language (L2) research, subject (S) - verb (V) order has been considered mainly as one of the properties of the NullS(ubject) Parameter (e.g. White 1985, 1986; Liceras 1989; Tsimpli & Roussou 1991). This parameter, formulated by Rizzi (1982, 1986) in the general spirit of Chomsky’s (1981) theory, suggested that one of the differences between non-NullS languages like English and NullS languages like Italian is that the former generally disallow postverbal S, while the latter allow both SV and VS order. Results from the above mentioned L2 studies have shown that L1 speakers of NullS languages generally disprefer VS order in English. Moreover, corpus-based studies (Rutherford 1989; Zobl 1989; Oshita 2000, 2004; Lozano & Mendikoetxea 2010) have revealed that L1 speakers of NullS languages such as Italian, Spanish, Arabic and Japanese use VS order in English almost exclusively with certain intransitive verbs like the ones in the following examples.

(1) In the town lived a small Indian... (L1 Spanish, Rutherford 1989: 178)

(2) ... . . . there exist two kinds of jobs. (L1 Italian, Oshita 2000: 315)

These verbs belong to a class of intransitive verbs called ‘unaccusative’ and differ from the other class of intransitive verbs, called ‘unergative’, on the basis of semantics and syntax. In unergatives, e.g. walk, laugh, S has the semantic role Agent and originates in the Specifier of VP (3); in unaccusatives, e.g. arrive, occur, S has the semantic role Theme (or Patient) and originates inside the VP in a V-complement position (4) (Perlmutter 1978, Levin & Rappaport-Hovav 1995, among others).

(3) [TP [DP Mary]i [VP ti [V΄ [V walked]]]]]

(4) [TP [DP Mary]i [VP [V΄ [V arrived] [ti]]]]]

In English the default SV order that surfaces both with unaccusative and unergative verbs is due to that S has to move to the specifier of Tense Phrase (TP) to satisfy the language-specific requirement for an overt element in this position and to get case. In null S languages the overt postverbal S originates within the VP and gets case through an Agree relation with a null expletive pronoun (pro) assumed to occupy the specifier of TP (see, e.g., Roussou & Tsimpli 2006: 319 and references therein; also see Section 2).

Importantly, VS order appears in English only with some unaccusatives which express existence or appearance, e.g. come, appear, exist, arrive and live. In this case the specifier of TP is filled by elements such as an expletive there (2), a Prepositional Phrase (PP) in locative inversion constructions (5), an adverb or another XP (see Biber et al. 1999: 912-3; also see section 4.2 for examples). Moreover, word order with unaccusatives is conditioned by discourse factors, such as the principle of ‘end focus’ (e.g. Leech & Short 2007, Chapter 7). Postverbal subjects tend to be focus, that is, they express new information (5) while preverbal subjects tend to be topic, that is, they refer to old information (6).

(5) In it, lives a family.

(6) This family lives in our neighbourhood.

Another factor conditioning speakers’ choice of word order has been accounted for by the ‘end weight’ principle (Quirk & Greenbaum 1977: 410-411), which states that that structurally complex constituents tend to appear at the end of an utterance for processing reasons. This principle can be illustrated by what is called ‘heavy Noun Phrase (NP) shift’. As shown by the following examples (from Hawkins 2004: 26), shifting a complex direct object NP before its simple complement PP (7) renders the sentence easier to parse, rather than keeping this complex object in its original position (8).

(7) Mary VP[gave PP[to Bill] NP[the book she had been searching for since last Christmas]]

(8) Mary VP[gave NP[the book she had been searching for since last Christmas] PP[to Bill]]

Note that structural complexity implies phonological heaviness: complex constituents generally consist of more syllables or words than simple constituents and, therefore, the former can be considered ‘heavy’ and the latter ‘light’. (See Section 4.1 about the criteria for such a distinction.)

The ‘end weight’ principle may affect word order also with unaccusatives: postverbal subjects tend to be more complex than preverbal ones (see Lozano & Mendikoetxea 2010 and references therein), as can be shown by (9) and (10) respectively.

(9) Then there arrived a man who knew of a proven remedy for the illness of the prince.

(10) A tall man arrived before noon.

Given the above, SV/VS order in English pertains to three linguistic interfaces: the lexicon-syntax interface (unergative vs unaccusative verbs), the syntaxdiscourse interface (focus vs. topic S) and the syntax-phonology interface (heavy vs light S). The aim of the present paper is to investigate whether these three interface conditions restrict word order in the Greek-English interlanguage by partially replicating Lozano and Mendikoetxea’s (2008, 2010) research, detailed in Section 3. We also attempt to trace L1 effect comparing our data with those in the latter mentioned study.

2. Subject Position in Greek

Greek is a NullS language allowing VS order both with unaccusative and unergative verbs regardless of whether S is topic or focus as illustrated by (11) and (12).

(11) Eftasan kapji tites (focus) / i fitites (topic) UNACCUSATIVE arrived some students / the students

(12) Edho dulevun kapji tites (focus) / i fitites (topic) here work some students / the students UNERGATIVE

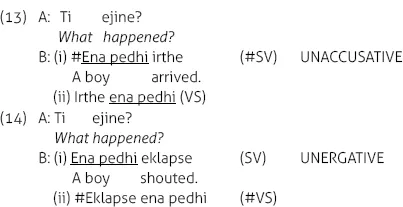

However, VS seems to be favoured with unaccusatives and SV with unergatives. This can be shown by comparing word order between and within the two verb classes in answers to a wide-focus question such as “What happened?” (13 vs. 14, cf. Lozano 2006: 373-74), where # indicates a pragmatically less felicitous word order (for references see, e.g. Lozano ibid.).

The underlying difference in subject position between unaccusatives and unergatives in Greek is illustrated by (15) and (16) respectively.

(15) [TP proi [VP [V’] [V irthe]] [ena pedhii]]]]]

(16) [TP [DP Ena pedhi] i [V eklapse] k] [VP [V’ ti] [V tk]]]]]

In the unaccusative VS structure the specifier of TP is assumed to be occupied by an expletive null p...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Section 3: Discourse Analysis - Gender - Lexicography

- Section 4: Language Acquisition

- Section 5: Language Disorders