Talmuda de-Eretz Israel

Steven Fine, Aaron Koller, Steven Fine, Aaron Koller

- 365 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Talmuda de-Eretz Israel

Steven Fine, Aaron Koller, Steven Fine, Aaron Koller

About This Book

Talmuda de-Eretz Israel: Archaeology and the Rabbis in Late Antique Palestine brings together an international community of historians, literature scholars and archaeologists to explore how the integrated study of rabbinic texts and archaeology increases our understanding of both types of evidence, and of the complex culture which they together reflect. This volume reflects a growing consensus that rabbinic culture was an "embodied" culture, presenting a series of case studies that demonstrate the value of archaeology for the contextualization of rabbinic literature. It steers away from later twentieth-century trends, particularly in North America, that stressed disjunction between archaeology and rabbinic literature, and seeks a more holistic approach.

Frequently asked questions

Information

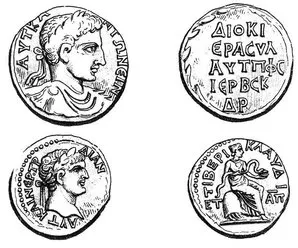

Tosefta Ma‘aser Sheni 1:4 – The Rabbis and Roman Civic Coinage in Late Antique Palestine

1 Unique Characteristics of Civic Coinage in the Roman Empire and Roman Palestine

Caracalla. Lower. Tiberias. Coin from the period of Trajan.

2 Coin Minting in Talmudic Sources: Tevi‘ah

Table of contents

- Studia Judaica

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- Mishnah Baba Metsia 7:7 and the Relationship of Mishnaic Hebrew to Northern Biblical Hebrew

- Mishnah Baba Batra 8:5 – The Transformation of the Firstborn Son from Family Leader to Family Member

- Mishnah Avodah Zarah 4:5 – The Faces of Effacement: Between Textual and Artistic Evidence

- Tosefta Ma‘aser Sheni 1:4 – The Rabbis and Roman Civic Coinage in Late Antique Palestine

- Tosefta Shabbat 1:14 – “Come and See the Extent to Which Purity Had Spread” An Archaeological Perspective on the Historical Background to a Late Tannaitic Passage

- An Illustrated Midrash of Mekilta deR. Ishmael, Vayeḥi Beshalaḥ, 1 - Rabbis and the Jewish Community Revisited

- Jerusalem Talmud Megillah 1 (71b-72a) - “Of the Making of Books”: Rabbinic Scribal Arts in Light of the Dead Sea Scrolls

- Jerusalem Talmud Sanhedrin 2,6 (20c) - The Demise of King Solomon and Roman Imperial Propaganda in Late Antiquity

- Genesis Rabbah 1, 1 – Mosaic Torah as the Blueprint of the Universe - Insights from the Roman World

- Genesis Rabbah 98, 17 - “And Why Is It Called Gennosar?” Recent Discoveries at Magdala and Jewish Life on the Plain of Gennosar in the Early Roman Period

- Leviticus Rabbah 16, 1 - “Odysseus and the Sirens” in the Beit Leontis Mosaic from Beit She’an

- Babylonian Talmud, Sukkah 51b - Coloring the Temple: Polychromy and the Jerusalem Temple in Late Antiquity

- Babylonian Talmud, Avodah Zarah 16a - Jews and Pagan Cults in Third-Century Sepphoris

- The Rehov Inscriptions and Rabbinic Literature – Matters of Language

- “This Is the Beit Midrash of Rabbi Eliezerha-Qappar” (Dabbura Inscription) – Were Epigraphical Rabbis Real Sages, or Nothing More Than Donors and Honored Deceased?

- The Piyyutim le-Hatan of Qallir and Amittai – Jewish Marriage Customs in Early Byzantium

- Afterwords

- Index