2.1 Etymological classes and phonological properties

It is well known that morphemes belonging to distinct etymological classes exhibit different phonological properties from each other. Yamato items are distinctive in that they are subject to a well-known compound voicing process called rendaku (Martin 1952; Hamada 1960; Nakagawa 1966; Sakurai 1972; Kindaichi 1976; Vance 1987; Satō 1989; among others). In this process, the initial voiceless obstruent of the second element of a compound is voiced (e.g., tori ‘bird’ > oya+dori ‘parent bird’). It occurs frequently in Yamato stratum, but loanwords do not undergo the process in general; see Vance (this volume) for a detailed discussion. In addition to rendaku, Yamato has a conspicuous restriction with respect to voicing; voiced obstruents (i.e., /b, d, z, g/) generally do not occur underlyingly in morpheme-initial position. Voiced obstruents are favored in morpheme-medial position in Yamato items such as haba ‘width’, kuda ‘tube’, kaze ‘wind’, toge ‘thorn’ (Hashimoto 1938; Komatsu 1981; NLRI 1984; Ito and Mester 1986; Labrune 2012; and see also Takayama, this volume, for a historical discussion).

Sino-Japanese items are characterized in terms of their unique shape. Sino-Japanese roots are in principle monosyllabic and variations of the syllable structure are limited to only the following four types: CV (ka ‘course, department’), CVV (doo ‘copper’, suu ‘number’, zei ‘tax’, kai ‘meeting’, rui ‘sort, class’), CVN (kin ‘gold’), or CVCV (betu ‘distinction, other’, koku ‘nation’). Though the last pattern has disyllabic structure, its underlying form is interpreted as monosyllabic /CVC/ and an epenthetic vowel (/u/ or /i/) is attached to the coda consonant to prevent a closed syllable from emerging (see Ito and Mester 1996 as well as Ito and Mester, this volume, for further discussion). In addition to monosyllabicity, palatalization of the onset consonant is characteristic of Sino-Japanese (Nakata 1982: 308–311). That is, Sino-Japanese contains a number of syllables in which the onset is palatalized, such as tya ‘tea’, kyuu ‘emergency’, and myoo ‘strange, mystery’. McCawley (1968: 62–66) is an early theoretical attempt to account for the phonological diversity among morpheme classes with respect to the distribution of palatalized (“sharp” in his terminology) consonants.

The foreign stratum has many characteristic properties that distinguish the items involved from those in other strata. First, the emergence of voiced geminates, as in beddo ‘bed’, is a conspicuous feature of the foreign stratum (Martin 1952; Ito and Mester 1995a,b; Katayama 1998; Irwin 2011; Labrune 2012; among others). Second, the voiceless bilabial stop [p] can freely appear as a licit surface segment in foreign items such as paipu ‘pipe’, puuru ‘pool’, supai ‘spy’, etc. (McCawley 1968: 77–85; Shibatani 1990: 166–167; Ito and Mester 1995a,b; Labrune 2012: 70–77; among others). Third, foreign items frequently contain novel CV sequences which do not appear in Yamato and Sino-Japanese words (Hattori 1979; NLRI 1990; Ito and Mester 1995a,b; Katayama 1998; Irwin 2011; among others). For example, syllables containing the voiceless bilabial fricative [ɸ] can appear with no restrictions in foreign words such as [ɸ]aito ‘fight’, [ɸ]iibaa ‘fever’, nai[ɸ]u ‘knife’, ka[ɸ]e ‘café’, and [ɸ]ooku ‘fork’, whereas it can appear only before /u/ in Yamato and Sino-Japanese. NLRI (1990: 62–74) and Irwin (2011: 75) present the list of CV moras found only in foreign items; see also Pintér (this volume) and Kubozono (this volume).

2.2 Phonological stratification

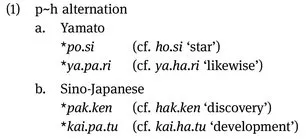

As long as we restrict our attention to the facts mentioned above, each etymological class seems to have its own phonological properties that characterize that class exclusively. However, it is not always the case that a phonology-based characterization of lexical strata directly corresponds to the etymological classification of lexical items in a one-to-one fashion. Some phonological properties are shared among two or more morpheme classes. The following data, for example, show that items in etymologically different morpheme classes pattern together. In (1)–(2) and the rest of the chapter, dots (.) denote syllable boundaries.

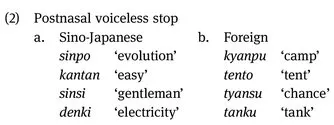

The voiceless bilabial stop [p] cannot appear as a syllable onset following a vowel either in Yamato or in Sino-Japanese. In these two classes [p] is converted to [h], as exemplified in (1). With respect to the illegitimacy of [p], Yamato and Sino-Japanese pattern together. On the other hand, the data in (2) show that another grouping can be established, from which Yamato is excluded. An obstruent in postnasal position can be voiceless both in Sino-Japanese and in foreign items, while it must be voiced in Yamato forms such as tonbo ‘dragonfly’, sinda ‘died’, kangae ‘thought, idea’, etc. On the basis of the phonological patterns in (1) and (2), the following two groupings can be established for these morpheme classes.

The phonology-based classification in (3) implies that the etymological partitioning of morpheme classes cannot account for all the properties of the synchronic configuration of the lexicon. The synchronic lexicon is, rather, organized gradiently, with some phonological properties overlapping between two (or more) morpheme classes.

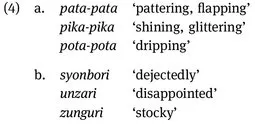

With reference to the phonological classification of lexical items, it is notable that mimetic items exhibit quite distinctive behavior with respect to the phonological regularities discussed above. Although mimetic items are of native origin etymologically, they are exempt from the prohibition against singleton [p]; it appears as a licit segment, as exemplified in (4a). Moreover, as shown in (4b), mimetic items are subject to the process of postnasal voicing, just like Yamato items. (“-” denotes a morpheme boundary.)

These data indicate the dual character of mimetics. While mimetics behave as if they belong to the native stratum with respect to the postnasal voicing (4b), they are the opposite of Yamato with respect to the legitim...