1. Introduction

Recent decades have witnessed a profound change in evaluating the relationship between linguistic categories and disciplines. It was cognitive linguistics, in particular, that highlighted their fuzzy nature. The attention of linguists was thus shifted to the problems of vague boundaries, prototypes and peripheries, good exemplars and poor exemplars. The situation within the traditional discipline of morphology is no exception. A number of morphologists, making use of the invaluable contribution of cross-linguistic typological research, have come to the conclusion that “the inflection/derivation distinction is not absolute but allows for gradience and fuzzy boundaries […] we are dealing with a continuum from clear inflection to clear derivation with ambiguous cases in between” (Haspelmath 1996: 47).

What are the reasons for this situation within morphology? A brief summary of these reasons is outlined in the first part of the article, followed by an overview of criteria proposed in the literature for the distinction between derivation and inflection. It will be demonstrated that none of these criteria are of universal validity due to numerous counter-examples from the languages of the world.

2. Reasons for fuzziness

2.1. The concept of new word

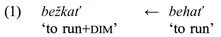

While it is generally accepted that derivational morphology deals with the formation of new words, i.e. with giving names to yet unnamed objects, it is not quite as clear what a new word actually is. Is a clipping or an acronym a new word? They do not denote a new object; instead they denote an “old” one by means of a reduced form. Even more evident is the fuzziness in numerous quantity-related categories. Thus, for example, do diminutives and augmentatives refer to new “objects”, like Slovak bežkať in (1)?

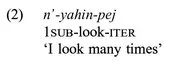

If so, then the comparative and the superlative degrees of adjectives should also be treated as derivational forms, although they are mostly discussed within inflectional morphology. And what about various aktionsart-categories, like frequentatives, dura-tives, intensifications, as in the following example from Wichi (Verónica Nercesian, pers. comm.),

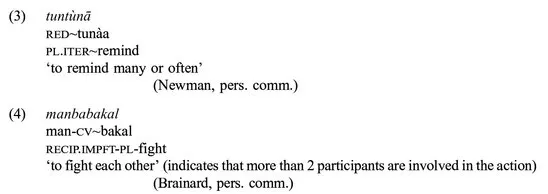

that are usually considered to be of inflectional nature? While Beard (1982) gives arguments in favour of the derivational status of the category of Plural in general, and Robins (1971) argues that number in Japanese is derivational, the plural of verbs has been perceived as a prototypical inflectional category. But there are also pluractional verbs like those in the Chadic language Hausa (3) and the Austronesian language Karao (4):

When discussing the situation in Kwakw’ala Anderson (1985: 30) argues in favour of the derivational status of affixes expressing tense, aspect, voice, modality and plurality, because they are (a) optional, and present only where necessary for emphasis or disambiguation; and (b) equally applicable to words of any syntactic function or word class. Anderson shows that, for example, xwakwəna ‘canoe’ has a future form xwakwənaƛ ‘canoe that will be, that will come into existence’. Its recent past form is xwakwənaxdi ‘canoe that has been destroyed’. In addition, Štekauer, Valera and Körtvélyessy (2012) point out that, compared to the “simple, inflectional” plural meaning ‘more than one’, pluractional verbs have, in principle, an additional meaning, like ‘repeated action’, ‘extent/ degree of action’, ‘simultaneity of action’, etc.

2.2. Language dependence

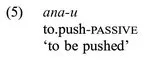

This brings us to another problematic point revealed by cross-linguistic research. In particular, one and the same category may be inflectional in one language and derivational in another, as pointed out, e.g., by Katamba with respect to diminutives (1993: 212). Let us furthermore call attention to the so-called D-element which in some languages, such as Hupa, a Na-Dene language spoken in North America, is mostly derivational, while in other languages, like Koyukon, it is more inflectional and productive (Thompson 1996: 353), or passivization in Udihe, an Altaic language, by the suffix -u (Nikolaeva and Tolskaya 2001: 287, 307) which − in contrast to the situation in the majority of languages − is formed by derivation from a restricted class of transitive verbs (5):

2.3. Crossing the inflection-derivation borders

Third, inflections may be borrowed by the derivational system, or they even may gradually acquire derivational status. Examples of the “borrowing” of inflectional affixes by derivation to produce new words are numerous. Sapir (1965: 57) reports a few instances of inflectional markers in Kujamaat Joola functioning as derivational affixes. So, for example, the passive suffix -i combines with -wɔl ‘to give birth’ to form kawɔli ‘birthN’ and the negative -ut can be combined with the theme -ju ‘to be in good health’ to form -ju:t ‘to be sick’. The status of -ut as a derivative is assured by its position. Sapir points out that the phrase ǝju: tǝlenorerit ‘he never pretends to be sick’ would be impossible if -ut in the double derivative formation -ju:tǝlenor ‘to pretend to be sick’ was functioning in its normal capacity as mood marker.

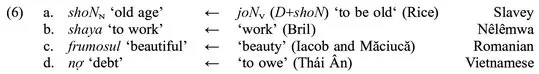

A change of inflectional paradigm is a device used in a number of genetically unrelated languages as illustrated in (6):

2.4. Affixal ambiguity

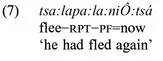

Ambiguous affixes also contribute to the fuzziness of the inflection/derivation distinction. Beck (pers. comm.) points out the abundance in Upper Necaxa Totonac of quasi-inflectional affixes. While these affixes are fully productive and thus carry a typical feature of inflectional affixes, they do not express obligatory morphological categories and do not constitute a paradigm (unlike prototypical inflectional morphemes). An example of one such affix expressing repetition is in (7):

2.5. Systematic ambiguity

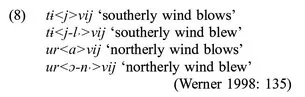

While in most languages the inflection/derivation ambiguities are restricted to individual cases/categories, the situation in Ket and all the other Jenissej languages is much more complex. Werner (1998) demonstrates that the whole system of verbs in these languages is fuzzy in this respect. Belimov (1991: 25) even assumes that word-formation and inflection are in fact a single process of forming new lexical units. Werner refers to verbs in Ket, derived by infixation, which have complete inflectional paradigms but lack an infinitive as a basic citation form:

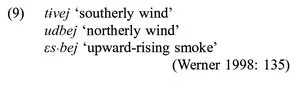

Interestingly, the potential infinitives are identical to nominal compounds given in (9).

2.6. Serving two masters

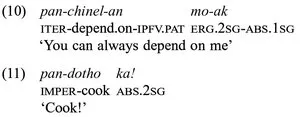

Some affixes serve two masters. The following example from Karao (Brainard, pers. comm.) shows that polysemy/homonymy can cross the inflection/derivation boundary (also because, on a more general level, the boundary between polysemy and homonymy is rather fuzzy). The Karao affix pan-/impan- can be a nominalizing affix, it can express, e.g., iterative action on a verb (10) but it can also signal imperative mood (!) as exemplified in (11):

To give a more familiar example, the English form -er can express the comparative degree of adjectives as well as various semantic roles, such as Agent (teacher), Instrument (cooker), Patient (foreigner), and a number of other meanings.

3. Criteria for the distinction between derivation and inflection

The following brief overview surveys various criteria recently proposed in literature and shows that, while prototypically the criteria are effective, they face counter-examples and/or various degrees of validity indicating their cline-like nature. Most of them draw on Dressler (1989), Scalise (1988), ten Hacken (1994) and Plank (1994).

3.1. Function

While derivational morphology has a semiotic function and contributes to lexical enrichment, inflectional morphology has the relational function of serving syntax or marking syntactic constructions with special word forms.

While inflectional morphology is obligatory in a syntactic construction, derivational morphology is not.

Apart from the counter-examples given in (6), one should mention conversion in the Slavic languages which is viewed as the derivation of a new word by changing its inflectional paradigm (Filipec and Čermák 1985: 104), and therefore labeled transflexion by Dokulil (1982). Stump (2005: 64) refers to Sanskrit, where the derivation of causative verbs is a productive process, but this process is simply based on the shifting of a verb from one conjugational category to another. Thus, the derivation of the causative verb from the verb dvis ‘to hate’ is b...