- 279 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume explores the complex relationship between primary agreement by means of object marking or differential object marking (DOM), and secondary agreement through clitics in non-standardized variation data from Limeño Spanish contact varieties (LSCV). As such it is concerned with diachronic as well as synchronic morphosyntactic variation of the third person object pronoun paradigm, so called clitics, as used in Standard Spanish and non-standardized Spanish contact dialects. The argumentation as well as the data presented cross diachronic and synchronic boundaries.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

This book is about the genesis of a subset of feature-reduced clitics and their syntactic/pragmatic functions in Limeño Spanish contact varieties of Peruvian Spanish. These clitics, which arise as non-standardized variation embedded in a variety of contact and second language acquisition scenarios, exhibit different grammaticalization stages and extended grammatical functions. The book presents a theoretically oriented description linking the clitic variability and innovation found in these dialects to language change in progress. The argument is then extended to show that these innovations are not restricted geographically but can be found in contact situations across the Spanish-speaking world.

1.1Clitics and argument marking

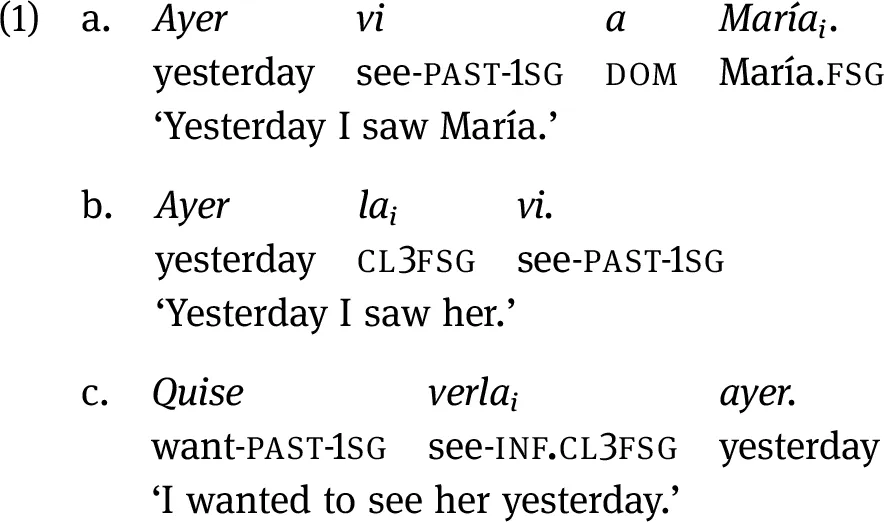

Clitic pronouns are morphological markers at the interface of syntax and phonology, morphology, semantics and information structure (Belloro 2007; Ordóñez and Repetti 2006; Spencer and Luís 2012; Zwicky 1985). They are phonologically unstressed bound morphemes and as such dependent on a verbal host. Proclitics as in (1b), occur as single words immediately before the verb, enclitics attach verbfinally as suffixes in (1c). In their morphology, Spanish clitics express the features person, gender, number and case, and play an important role in argument marking (Harris, 1995). As anaphores, feature-agreeing clitics replace propositions or noun phrases as in the feminine clitic la in (1b) and (1c) referring to the noun phrase María in (1a).

In object-verb agreement, Spanish shows dependent- and head-marking as in showing case and agreement features in the two core grammatical functions, namely the indirect object and the direct object (Bresnan 2001c; Nichols 1986). Dependent-marking uses a syncretic form a to mark indirect objects with dative case obligatorily and direct objects with accusative case differentially (differential object marking [DOM]). Head-marking obtains through a set of feature-specific clitic pronouns (number, gender and case [dative and accusative]), crossreferencing the object on the verb subject to semantic and pragmatic constraints. The combination of head- and dependent marking strategies is shown in the direct object clitic doubling construction in (2) where two elements, feature-specifc clitics (la carries feminine gender and lo masculine) and differential object marking specify information about one single argument, the lexical direct object.

Co-occurrence of head- and dependent marking also extends to non-argument or discourse structures via word order arrangements such as preposing or left dislocation1 in (3a) and right dislocation in (3b), marking different grammatical relations and signaling pragmatic functions in particular topicality. Note that in (3), the masculine lo agrees in number and gender with its referential noun phrase al chico.

Clitic doubling and topicalization strategies are governed by a complex configuration of morphosyntacic, semantic and pragmatic factors, and are subject to diachronic and synchronic variability across all Spanish varieties. In language contact situations, hybrid/split or new clitic systems may develop.

These new developments in monolingual and bilingual Spanish varieties are the focus of this book. They are illustrated by the following three clitic-doubled structures from two closely related contact varieties, Limeño Spanish contact varieties and Andean Spanish. All examples are considered non-standard or ungrammatical by educated speakers of Spanish across the Spanish speaking world.

Firstly, the emergence of invariant accusative lo crossreferencing a plural feminine human object with optional casemarking in (4a) and a feminine inanimate definite object (4b) with case marking.

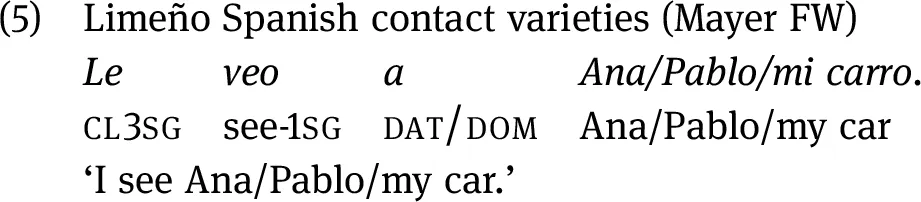

Secondly, invariant accusative lo covaries with invariant dative le in extended accusative doubling, crossreferencing a feminine/masculine human and a feminine inanimate object with casemarking as shown in (5). The extension of le to inanimate objects depends on geographic region and intensity of contact. Note the ambiguous role of the syncretic form a as either dative case or differential object marker (accusative case).

Thirdly, another function of invariant lo is locative doubling. The syncretic form a in (6) is a locative preposition.

Examples (4)–(6) show the complex argument marking system using clitics of non-standardized Spanish. Educated and dialectal norms perform the same functions with feature-specifying clitics and restricting differential object marking to animate, definite and specific noun phrases and determiner phrases.

Before delving deeper into the subject, I introduce some definitions. Throughout this book when I use the term Spanish, I refer to the educated oral and written norm of Spanish spoken around the world as a first and as a second or additional language. Spanish thus refers to the standardized written and oral norm of the Spanish language as laid out and monitored by the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language (Real Academia Española) in Spain and its 21 affiliated Academies in Latin America, the United States and the Philippines. To cover dialectal variability across all Spanish speaking countries, I specify the broader region, for example Peninsular Spanish or Latin American Spanish, as well as the local region as in River Plate Spanish (or Rioplatense Spanish). Lima Spanish refers to the educated and standardized norm as used in all official documents and spoken by educated speakers in Lima and elsewhere in Peru.3

Limeño Spanish contact varieties are mainly acquisitional varities on a continuum dependent on varying access to formal education. This is why I refer to those varieties as ‘non-standardized’ in the sense of Bresnan (1998), referring to a dialect continuum exhibiting extensive microvariation embedded in a range of linguistic and extra-linguistic factors, among them importantly non-standard input and undereducation as further described in section 1.4.1 below. Andean Spanish is mainly an oral Spanish dialect continuum reaching from the southern tip of Colombia to the northern Santiago de Estero region in the Argentine. Another closely related Spanish dialect continuum is Amazonian Spanish. The main difference between Spanish and non-standardized Spanish is that the latter is mainly oral and characterized by lack of or limited access to formal education. In this book examples from Spanish are of written or oral educated origin; examples from Limeño Spanish contact varieties are naturally occurring oral data collected in fieldwork.

1.2Variability and innovations in argument marking

Differential object marking and clitic doubling are the two strategies exhibiting great variability in marking topical arguments.

1.2.1Differential object marking

Differential object marking is a widely attested strategy that many genetically unrelated languages apply to optionally mark a certain range of direct objects, depending on their intrinsic properties (see parts 1 and 2 of chapter four). What triggers differential object marking is language specific and may vary over time. Objects are ranked for their prominence on a two-dimensional scale, based on the interaction of animacy and definiteness (Bossong 1991, 2003; Aissen 2003). Some languages change this scale to animacy and specificity, for example Turkish, Persian, Urdu/Hindi, River Plate Spanish and Limeño Spanish.

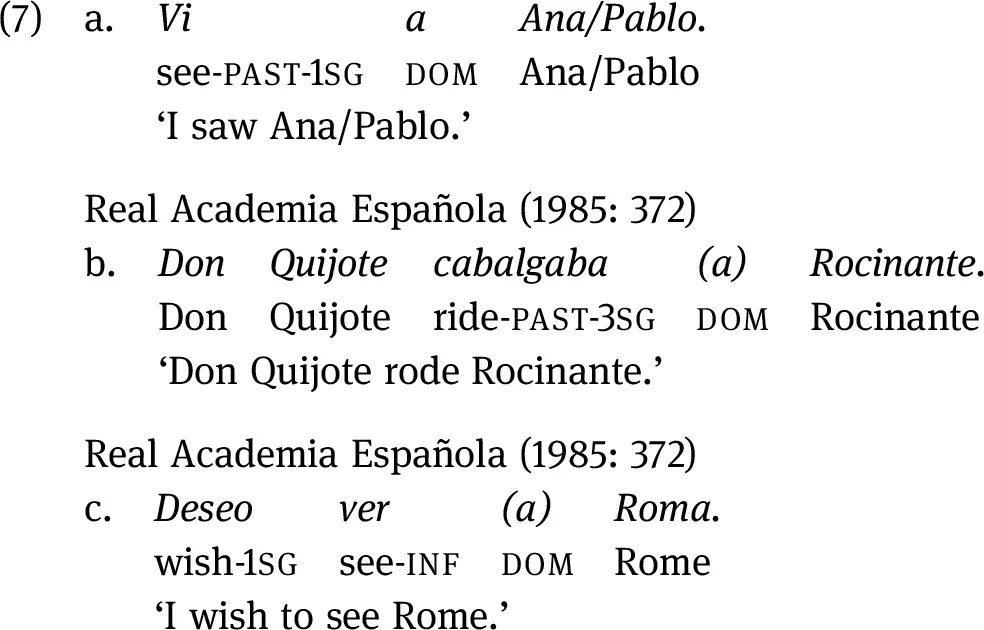

In Peninsular and most Latin American Spanish dialects, differential object marking obligatorily marks direct objects bearing the features human, animate and definite, as in (7a), extending optional marking to animate and specific personified animals, as shown in (7b), and inanimate and specific places, as in (7c), in accordance with norms set out by the Real Academia Española. In (7a) it is important to note that although both the subject and the object share the highest ranking on the animacy hierarchy, the resulting topicality of both arguments cannot give rise to clitic-doubled constructions in most Spanish dialects. Notable exceptions are River Plate Spanish and Lima Spanish as shall be shown shortly.

To receive differential object marking, both inanimate objects in (7b) and (7c) must be specific, which means they must be referentially recoverable from the context, or identifiable. According to Lambrecht (1994: 78), “the speaker assumes that it4 has a certain representation in the mind of the addressee which can be evoked in a given discourse.” This topic will be discussed in detail in chapters four, five and six.

1.2.2Clitic doubling

In Peninsular and most Latin American Spanish dialects, direct object clitic doubling or accusative doubling requires differential casemarking (DOM) and is subject to different and varying semantic (animacy and definiteness) and pragmatic (topicality) constraints. Co-occurrence of head-marking and dependent-marking in direct object clitic doubling is subject to Kayne’s Generalization (8), again in Standard Spanish varieties (Kayne 1975).

| (8) | The principle stipulates that clitic doubling is only possible when the doubled noun phrase has a case assigner such as a preposition. |

In Peninsular Spanish, direct object clitic doubling with gender and number distinct accusative clitics as in (9) is obligatory for pronominal noun phrases and constrained to these (Bello 1984; Real Academia Española 1985).

In Peninsular and most Latin American dialects of Spanish, extension of clitic doubling and differential object marking to inanimate arguments as in (10) is considered ungrammatical. Generally, inanimate, non-specific and definite noun phrases do not show head- and dependent-marking.

However, in some Latin American varieties of Spanish we see variability in the application of those prescriptive grammatical rules, specifically in relation to clitic–object agreement, thus representing a new local standard norm.

For instance, liberal clitic doubling dialects such as River Plate5 and Lima Spanish in (11) extend clitic doubling and differential object marking to specific inanimates with agreeing (coreferential) clitics, thus ensuring identifiability.

Extension of clitic doubling to definite/specific animate and inanimate direct object arguments with feature-specifying clitics constitutes the first Latin American Spanish innovation regarding clitic doublin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Table of contents

- List of tables

- Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The nature of clitics

- 3 Objects, case and clitic doubling

- 4 From syntax to information structure

- 5 Variation and continuity in time and space

- 6 Contact and change

- 7 Conclusion

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Spanish Clitics on the Move by Elisabeth Mayer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Historical & Comparative Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.