![]()

____

Part I: Antiquity and Late Antiquity

![]()

Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt

The Palace of the Roman Emperors on the Palatine in Rome

„Es war jedoch erst der Flavier Domitianus, der auf dem Palatin den Palast erbaute, der von nun an die zentrale Residenz der römischen Kaiser werden sollte. Der Palast bestand aus der Domus Flavia, dem öffentlichen, und der Domus Augustana, dem privaten Bereich. Beide waren um jeweils ein Garten-Peristyl gruppiert, in der Nähe befand sich ein großer, ornamental angelegter Garten, hippodromus genannt. Hohe Fassaden mit Säulen, die zu riesigen Vestibülen und monumenta-len Audienzund Speisehallen führten, charakterisierten den Palast, der seine Umgebung weit überragte“1. Thus the Palatine is briefly described under the entry of “Palast” by Inge Nielsen in the encyclopedia Der Neue Pauly.

The new building which the emperor Domitian erected on the highest point of the Palatine and inaugurated in the year A. D. 922 has always been regarded as a counterweight to its predecessors, in stark contrast to the residence surrounded by an extensive park built by the Emperor Nero after the great fire of A. D. 64 (Tacitus, Annales, 15,42)3. Completely new concepts of architectural space were developed, especially in the Domus Aurea where, for instance, elements of bath architecture were first introduced into domestic architecture through the building of an octagonal, domed hall4. The Domus Aurea on the Oppian Hill, modelled as a “mega-villa”5 after a type of suburban villa, served rather as a retreat and was part of what Marianne Bergmann called Nero’s “concept of otium” (Fig. 1)6. According to prevailing scholarly opinion, the Flavian Domitian could not and did not want to take over Nero’s palace for political reasons. The concept of the palace was changed radically and the Palatine returned to its original significance as the only official residence.

Already in antiquity the building complex of Domitian was described as the second Capitolium, a building with which the emperor could clearly demonstrate his power as ruler of the Roman world7. Many ancient writers, such as Statius, Martial and Plutarch8 admired the large size, the grandeur and the luxury of the palace, and described it as a great work of Domitian and his architect Rabirius9. Even to this day, researchers still accept as valid the ideas of Alfonso Bartoli, who excavated the Domus Augustana at the beginning of the 20th century but never published the results in detail. He stated that the Domus Augustana, together with the Domus Flavia, was the centerpiece of the palace buildings erected by the emperor Domitian10.

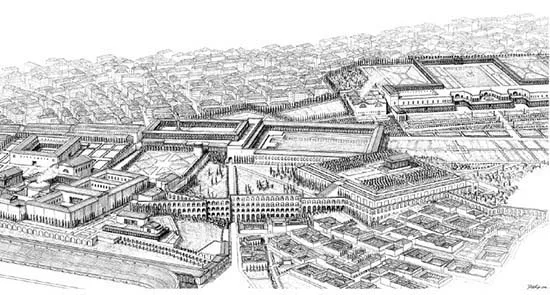

Fig. 1 Domus Aurea. Hypothetical reconstruction of the “Mega-Villa”.

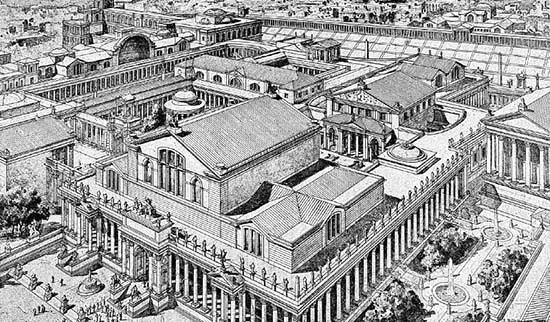

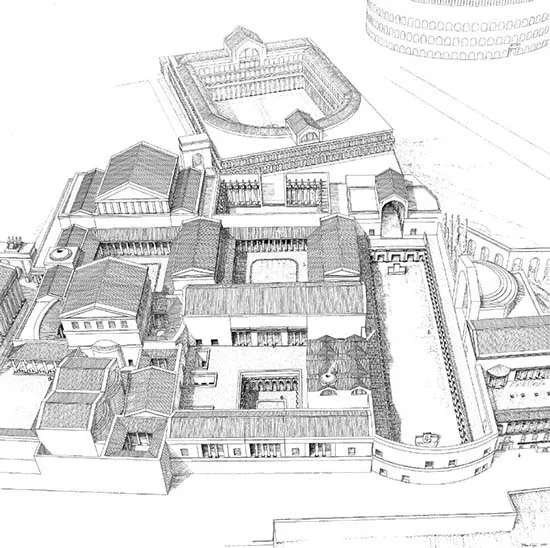

Fig. 2 The palaces of the Roman Emperors on the Palatine. Reconstruction after Bühlmann 1908.

Formed by these descriptions and the imaginative reconstruction drawings of the 19th and early 20th century (Fig. 2)11, the picture of a uniformly planned and executed Domitianic palace complex is firmly established in all handbooks of Roman architecture and consequently also in our minds12. The scholarly literature considers this the quintessential prototype of a Roman imperial palace. Moreover, it emphasizes the presumed design, in which rigid symmetrical axes unite the sequence of rooms to form a harmonious, block-like, closed and introverted complex13. So far this opinion has hardly ever been questioned.

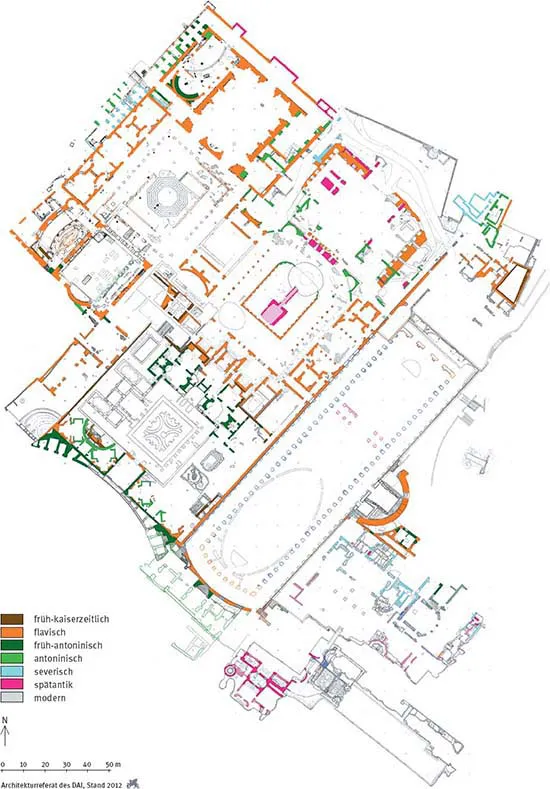

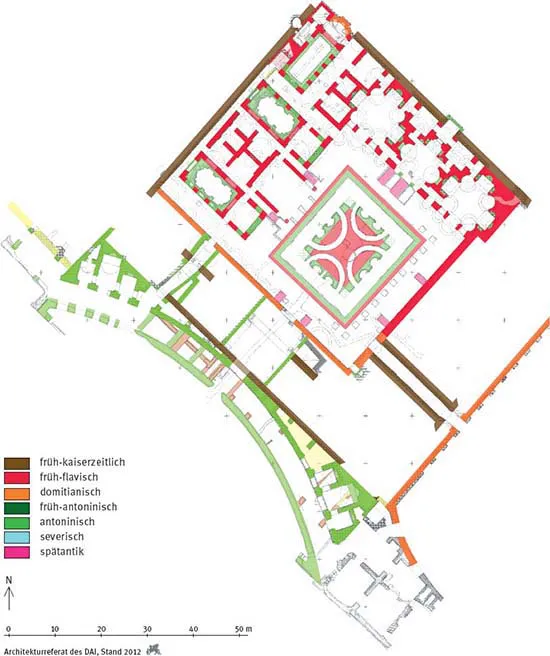

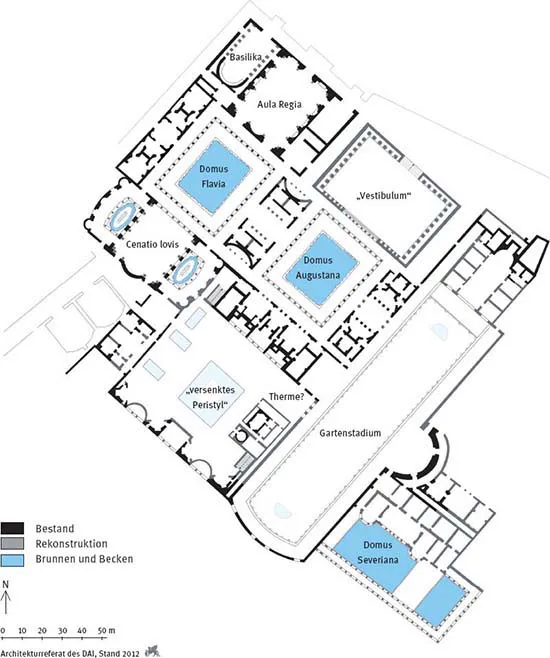

Fig. 3 Domus Flavia, Domus Augustana, “Gardenstadium” and “Domus Severiana”. The building phases of the main level.

Despite the importance of the Domus Flavia and the Domus Augustana for the understanding of the Flavian Palace, they were almost entirely unexplored prior to Bartoli’s first documentation14. The same is true for the adjacent parts, like the so-called Gardenstadium and the so-called Domus Severiana (Fig. 3). At the request of the Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Roma and under the aegis of the Departments for the History of Architecture and Survey at the Brandenburg Technical University of Cottbus and also, since 2004, the Department of Architecture of the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin, we were given the opportunity to investigate large parts of the palace15. Until 2013 we had the opportunity to compile detailed documentation and to analyse the structures of the “Domus Severiana”, the “Gardenstadium”, the Domus Augustana and the Domus Flavia, thus the major part of the palace structures on the Palatine. It was particularly this architectural investigation that has helped us to better understand the development of the palace of the Flavian to the Maxentian period16. It has also revealed new and unexpected results for the Flavian phase of the palace.

The Flavian Phase of the Palace

From the new results, it is clear that the so-called core of the Flavian palace is not based solely on the plans made during Emperor Domitian’s reign17. The key insight for a better understanding of the building phases, which has shed new light on the area of the Domus Augustana, comes from the analysis of the so-called sunken peristyle of the Domus Augustana, generally regarded as a project of Domitian. Since this complex could be entered only through a narrow staircase, it is usually seen as a private retreat area18, but there is convincing evidence on the basis of several criteria, that there was an earlier Flavian construction phase, probably dating to the time of the reign of Domitian’s father, the emperor Vespasian (Fig. 4)19. This phase comprises the entire northern area around the “sunken peristyle”, to which the row of three rooms to the north also belongs, exceeding the complicated layout of the rooms of Nero’s Domus Aurea20. In the western wing was a group of rooms with a central oecus, a large banquet room, surrounded by further dining rooms. The rooms were orientated towards a huge water basin with a rectangular island in Flavian times. The striking form with the pelta motif is a change, which most likely belongs to the Hadrianic period21. This part of the palace should not be interpreted as the private rooms of the emperor, but as a separate series of dining rooms for use in larger banquets, together with large halls and more private rooms22. They provide an ideal banquet opportunity to accommodate a great number of guests in different, interconnected rooms, while giving the emperor the chance to visit these rooms in succession23. The problematic distinction between the various parts of the palace as public and private, as appears in various publications, is therefore not correct24. There is also considerable evidence that this area was originally planned with one story, which would have emphasised even more the concept of a sunken peristyle (Fig. 5)25. Despite these aspects for this early Flavian phase, the southern half cannot be reconstructed with certainty. This area was clearly closed off by a straight wall, and no connection existed between the Circus Maximus and the level of the “sunken peristyle” (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4 Domus Augustana. The building phases of the “sunken peristyle”.

Fig. 5 Hypothetical reconstruction of the Flavian phase of the palace.

Even more surprising than the early Flavian phase are the conclusions that can be drawn from the brick stamps found in situ in the large exedra in front of the “sunken peristyle”. The exedra could not have been built prior to the early 2nd century A. D. and therefore must date to a phase of modification (Fig. 4)26. Only during this expansion of the palace towards the Circus Maximus was the two-storied columned portico added. Until then the Flavian palace, behind a solid wall (at least on the lower story), turned its back, figuratively speaking, on the Circus Maximus.

Fig. 6 Domus Flavia, Domus Augustana, “Gardenstadium” and “Domus Severiana”. Reconstruction plan of the main level in the Flavian phase.

There is also evidence that the main level of the Domus Augustana was not built in one single phase (Fig. 3)27. It seems that the peristyle courtyard with the huge rectangular water basin was conceived in the time of Domitian, as was the general plan of the Domus Flavia. Extremely difficult to interpret are the remains of the structures between this peristyle court and the Vigna Barberini, the so-called “no man’s land”28. The most conspicuous structure is a more than 2 m wide foundation with huge holes, originally filled with travertine blocks. The only explanation for this opus caementicium foundation, which can be dated by its characteristics to the Domitianic period29, is that it supported a wall with pillars next to it, a building type we know very well from the Forum Transistorium30. There...