eBook - ePub

Intonation in African Tone Languages

- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Intonation in African Tone Languages

About this book

This volume brings together two under-investigated areas of intonation typology. While tone languages make up to 70 percent of the world's languages, only few have been explored for intonation. And even though one third of the world's languages are spoken in Africa, and most sub-Saharan languages are tone languages, recent collections on tone and intonation typology have almost entirely ignored African languages. This book aims to fill this gap.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

II Western Africa

Michael Cahill

Kɔnni Intonation

Michael Cahill, SIL International

Abstract: Kɔnni [kom] is a Gur language of northern Ghana, with a combination of normal and unusual prosodic characteristics. Downstep is the manifestation of a floating Low tone, and the associative construction is marked by a floating High tone. The OCP is shown to be inactive with regard to both High and Low tones. Kɔnni exhibits true tonal polarity on one nominal suffix, not the commonly analyzed tone dissimilation. The intonation portion of this study presents pitch patterns of basic, compound, and complex sentences. Direct and indirect quotations are examined in complex sentences, along with elements fronted for emphasis. Kɔnni has an unusual pattern for polar questions, with at least three distinct tonal strategies evident. The paralinguistic intonation patterns relating to several emotional states are presented and related to cross-linguistic studies. Unlike most of the languages in this volume, with the limits of the present data, no boundary tones are evident.

Keywords: Tone polarity, polarity, OCP, paralinguistic, emotions, duration, syllable as TBU, downstep, floating tones, associative tone, tone spreading, declarative sentence, compound sentence, quotes, direct quotes, indirect quotes, fronting, paragraphs, content questions, polar questions (or “yes/no questions”), lax question intonation, anger, surprise, bored, emphasis, contemptuous, discourse

1Introduction

This chapter7 aims at providing a beginning look at some aspects of intonation in Kɔnni [kma], a Gur language spoken in the north of Ghana. It is not a large language compared to other Ghanaian languages, with Ethnologue listing the population at about 3800 (Lewis, Simons, and Fennig 2016) from a 2003 report, but a more recent estimate being about 8,000 (Konlan Kpeebi, pc). It is bordered by the more populous Mampruli, Buli, and Sisaala languages. Naden (1986), on the basis of a limited survey trip, produced the first sketch of Kɔnni phonology, morphosyntax, and vocabulary. For specific tonal phenomena, Cahill (2000, 2004) provides analysis of the Kɔnni tonal associative morpheme and tonal polarity, and the most thorough presentation of all aspects of Kɔnni phonology and morphology, including tone, is Cahill (2007). The only previous publications on Kɔnni intonation are a brief mention of polar question intonation in Cahill (2007), a more detailed examination of this topic in Cahill (2012), and a conference presentation on Kɔnni emotions and intonation in Cahill (to appear).

A particular instance of intonation can be classified as either structural (phonological, indicating linguistic boundaries or functions) or paralinguistic (e.g. indicating emotions and attitudes, which have gradient values of pitch) (Gussenhoven 2004, Ladd, Sherer, and Silverman 1986, Ladd 2008). Examples of each of these are examined for Kɔnni. Structural intonation, being phonological, adds or replaces specific tones. We will see this especially in Kɔnni polar question intonation. Paralinguistic intonation is most evident when discussing emotions in Kɔnni, but also appears in other contexts.

A broad question is how intonation can function in a tone language, since both affect pitch. Cruttenden (1997: 9–10) writes that tone languages may still use “superimposed intonation” in four ways:

–the pitch level of the whole utterance may be raised or lowered

–the range of pitch may be narrower or wider

–the final tone of the utterance may be modified

–the normal downdrift of a sentence may be suspended

All except the third bullet would be cases of paralinguistic intonation patterns. More recent studies, including several in this volume, would modify this to include not only utterance-final modifications, but phrasal boundaries. In Kɔnni, we will see cases of all these except the last.

Thus far the term “intonation” has been used in the common way, to refer to variations in pitch that contribute meaning to an utterance. However, this is not universal; a broader view is that intensity and duration are also included in “intonation,” as Ladd (2008: 4) specifically notes. Hirst and DiCristo (1998: 3–8) have a detailed discussion of the oft-confusing terminology of prosody, intonation, etc., concluding that intonation proper does include the physical properties of duration and other characteristics. This chapter includes measures of duration as well as of fundamental frequency. We will see duration coming into play in polar question intonation, as well as in the paralinguistic aspects of intonation related to emotional expression in Kɔnni.

Since intonation interacts with tone, I first present the broad patterns of tonal inventory and phenomena for Kɔnni in Section 2, including some patterns which are cross-linguistically unusual. Section 3 begins the presentation of intonation with an examination of declarative sentences, beginning first with simple sentences, then compound sentences, complex sentences which encode direct and indirect quotes, and finally sentences with fronted elements. It will be seen that there is no clear evidence for boundary tones thus far in Kɔnni. Also, phonological phrasing, significant in some of the other chapters in this volume, is likely relevant in Kɔnni, but is not evident from the data currently at hand, and will not be discussed in this chapter. Section 4 presents patterns of question intonation, briefly covering content questions (which have a pattern identical to declarative sentences), but with the bulk of the section concentrating on polar questions. These have some resemblance to Rialland’s (2007, 2009) typological patterns, but in Kɔnni they are quite distinct in having not one, but three patterns. Section 5 examines the paralinguistic intonation patterns produced by several different emotional states, and compare with scholars’ findings in other languages. Section 6 offers some concluding observations, and directions for future research.

2Basic patterns of tone in Kɔnni

The patterns in this section8 are condensed from Cahill (2007), in which the interested reader can find more data and argumentation, as well as detailed analysis from an Optimality Theory perspective.

2.1Tonal inventory and the tone-bearing unit

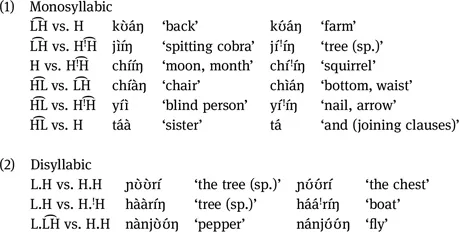

Kɔnni has two underlying tones, High (H) and Low (L). These combine as rising (LH) and falling (HL) contours on single syllables, as well as a High-downstepped High (H!H) on a single syllable as a second type of falling tone. The tone-bearing unit is the syllable, to which one or two autosegmental tones may associate. A sample of contrasts is given below. Tones are marked on every vowel in this chapter, even if, as in the case of chííŋ below, there would be only one auto-segment associated with the entire syllable.9

African languages have been variously claimed to have either the syllable or the mora as the tone-bearing unit (TBU) (Odden 1995). For Kɔnni, distribution and alternations both support the syllable as TBU. Surface syllable types are V, N, CV, CVC, CVN, CVV, and CVVN. Only the last three stand as independent words. Kɔnni allows either one or two associated tones per syllable; this distribution is shown in (1) and (2). If the mora were the TBU, one expected pattern would be three distinct tones on a trimoraic word CVVN, e.g. *gàáŋ̀. However, such a pattern is unattested.

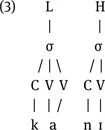

A more complex line of evidence pertaining to the TBU is the behavior of words such as kàànÍ ́‘one’ with respect to spreading of High tone. As discussed in greater detail in Section 2.4, a HLH underlying tone is realized as H!HH on the surface. Thus in zàsÍŋ́ ‘fish’ and ŋ̀ wó !zásÍŋ́ ‘I lack fish’, when the High-toned verb wó precedes the LH of the noun zàsÍŋ́ , this creates an underlying HLH sequence which surfaces as H!HH. However, if two Low-toned TBUs intervene between the High tones, the underlying HLLH is unchanged, as in ŋ̀ wó dàmpàlá ‘I lack bench’. The question, then, is whether the first two moras of kàànÍ ́[kaa] act like two TBUs, with two instances of Low, or one.

If kàànÍ ́is preceded by a Low tone on the head noun, the two first moras [kaa] are on the same Low pitch and the second syllable [nɪ] is High-toned, as in kàgbà kàànÍ ́‘one hat’. However, if the preceding noun ends in a High tone, both syllables of kaanɪ are pronounced on the same pitch, as a downstepped High tone, as in zàsÍŋ́ !káánÍ ́ ‘one fish’. The long vowel in kaanɪ acts as if it were a single TBU with a single Low tone, as in zàsÍŋ́ rather than dàmpàlá in the preceding paragraph.

Therefore the long vowel in kàànÍ ́and other words can be represented with a configuration something like the following (omitting a moraic tier):

For brevity’s sake, however, I will use

as a shorthand representation for (3) above, with the L tone to be regarded as being linked to the whole syllable k...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- I Northern Africa

- II Western Africa

- III Eastern Africa

- IV Eastern Central and Southern Africa

- Notes on contributors

- Index

- Endnotes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Intonation in African Tone Languages by Laura J. Downing, Annie Rialland, Laura J. Downing,Annie Rialland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.