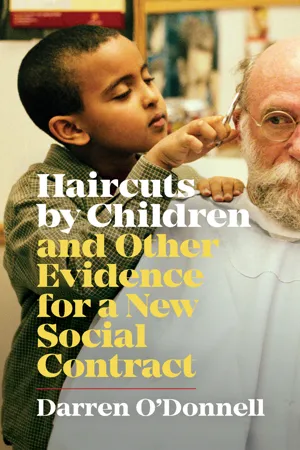

1

CHILDREN VS. CAPITALISM

Iconsider myself an embarrassed revolutionary, hoping for rapid, wide-scale social change toward higher levels of equity and fairness. I don’t think it’s too much to ask; I just want to live in a world where everyone has enough and no one has way too much. I’m embarrassed because not only is wide-scale social change toward fairness exactly what is not happening, things are actually swinging in the other direction, with increasing momentum, and maintaining this hope feels, more and more, like idiotic naïveté. No one seems to have a new plan, or at least a new plan able to galvanize critical mass, and none of the old plans seem to have worked out too well. The idea of tossing a wrench into the gears of capitalism just hasn’t panned out, so maybe we need to rethink things and find something else to toss in. I’m thinking children.

I’m not the only one who thinks children should be playing a much bigger role in the world. Article 12 of the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC; Appendix 3) provides a basis for a way to think about young people as participants in the social order. It reads: ‘States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child.’

While ‘expressing views’ is a narrow way to describe participation, Article 12 has been taken up and commonly understood as protecting children’s participation rights.1 These rights should need protecting for all the reasons regularly cited when psychologists, social geographers, and legal scholars take up the topic, as they often do: for the young people to develop a sense of control, increased ability to handle stressful situations, enhanced trust in others, self-esteem, and the feeling of being respected, to enhance education and development, to learn how to respect others’ views, and more.

But the reach of these rights is actually extensive: ‘all matters affecting the child.’ That’s a pretty big list. It is hard to think of any important social or political institution, process, or system that doesn’t affect young people: the market, the education system, the judicial system, the electoral system, the entertainment industry, the medical industry, almost all technology, and on and on. The list is almost endless, and can pretty much be summed up with one word: everything. Everything affects children – but it’s bigger than the individual kids. I’m all for helping every child achieve her best potential, of course, but here I want to focus on the ways that increased participation of children and young people will make for a better society in general. There are advantages to all of us when children are among us. On a simple level, hanging out with kids encourages calm civility – after all, no one relishes the idea of having a yelling match in front of a crowd of four-year-olds – and children are expert at small joys, having a total mastery of play, an attribute many adults find challenging. Imagine if kids were almost always everywhere.

I am proposing the utopian idea that children should not be corralled off in some district of life known as childhood, where their contribution is – if allowed at all – limited. Children and young people should be folded much more into the decision-making processes that drive our society, the level of their participation read as a barometer of a given institution’s commitment to human rights. Further, the increased participation of children across as many aspects of life as possible – but most importantly, the world of work – might be a stealthy way to smuggle in a little equity and fairness without triggering too many alarm bells. This is a vision of children as contributors of an expertise arising from their particular youthful capacities, an expertise that could change the game, yielding widespread social change and a realignment toward more equitable conditions for all. The effects on the systems we rely on might well be revolutionary – it could topple capitalism.

I know that sounds even more idiotic than sitting around and waiting for the revolution. But consider what the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child had to say in 2006 about that very modest question of the child’s right to express his or her views:

Recognizing the right of the child to express views and to participate in various activities, according to her/his evolving capacities, is beneficial for the child, for the family, for the community, the school, the State, for democracy … The new and deeper meaning of this right is that it should establish a new social contract [my italics]. One by which children are fully recognized as rights-holders who are not only entitled to receive protection but also have the right to participate in all matters affecting them … This implies, in the long term, changes in political, social, institutional and cultural structures.2

The committee understands the implications of implementing the 1989 UNCRC: there will have to be some pretty big changes, extending well beyond the benefits to the individual child, changes that will affect everyone and everything. The idea that incorporating children more fully has the potential to challenge stubborn ideological deadlocks is supported by the fact that the UNCRC is so widely ratified, with all countries but the U.S. on board. That’s a pretty impressive consensus. The presence of kids can help us agree on even difficult issues, a view the UNCRC advances, with the no-brainer that children have the potential to aid understanding among cultures and societies by approaching questions of morality and ethics in ways very different from adults. Someone’s religion is not likely to cause anxiety when there’s a game of tag to be played, and fairness – accepting equitable redistribution – is so totally logical to most children that they won’t shut up about it.

I realize I’m taking a risk in proposing this idea, the same risk that anyone who does any kind of work with kids takes on and, in fact, the risk that children themselves constantly face: I may not be taken seriously. But being quickly dismissed is a bad reason to stop talking, thinking, and trying. When shifts in attitudes come, they can come fast, leaving the world utterly transformed. And it does need to be transformed. A change is required, if not a massive overhaul, in the way a capitalist system has concentrated wealth in an increasingly small and rarefied stratum of the social hierarchy. We need a change in who benefits from our social, economic, and political activities. Inequity is rising fast, and it is primed to look like nothing we’ve ever seen before.3 Some futurists, like Dr. Oliver Curry, an evolutionary theoriest from the London School of Economics, even predict we’re risking the evolution of two species – one tall, healthy, and wealthy and the other, short, dim-witted, and poor.

The left’s pivot over the last thirty years toward a politics of identity has been blamed by some commentators for driving people apart and contributing to the recent rise of an extremist, racist, sexist, homophobic far right. But whether that’s true or not, the politics of identity have not provided the tools to create a movement with enough mass to really get up in capitalism’s ugly face. Judith Butler, a leading figure in challenging the gender binary in both academic and popular contexts, also has doubts about the efficacy of identity politics. She believes it ‘fails to furnish a broader conception of what it means, politically, to live together across differences’4 and she turns to the idea of precarity, or precariousness – living with no stable, reliable, and consistent employment – as a concept to rally around, a site of alliance.

And this is where the kids come in. If we’re looking for a population with nearly infinite identities expressed by the individuals within it, all of whom share the condition of precarity, we don’t have to look much further than children, even the richest of whom are denied many basic rights, including the right to work for money. Children are everywhere, all identity groups have them, and all of us, no matter our identity or our politics, have been a child and experienced the acute powerlessness that is the child’s condition. Can the child – and efforts to infiltrate much of the world with the presence of children – provide a strategy for destabilizing the status quo? And if so, can this strategy attract the critical mass currently missing from the many fractured movements that wrestle with the question of fairness?

Our understanding of what it means to be a child and what children are capable of contributing is rapidly evolving. I believe we do have the possibility of both subverting business as usual and finding a common cause to organize around, a stealthy little cause that, at first, seems naive and innocuous – sure, let the kids in – but that might radically revolutionize the world. So let’s get on with this revolution, let’s parachute the little kids in everywhere, like tiny anarchic guerrillas, with the first question being, how do we get the whippersnappers back to work, one area where capitalism has particularly strong purchase?

In this book, I turn to recent developments in the arts and cultural sectors in which children and young people increasingly play important leadership roles. Working with kids to make financially viable, aesthetically successful art for the international performing arts market – as I do – is, admittedly, a narrow case study, but many of the benefits kids bring if fully included in this sector map fit neatly onto places where adults and children already interact: the family, school, extracurricular activities, online, and, oftentimes, the market. Some of the principles of our engagement with children in the arts can inform other pathways to including kids in the everyday institutions that make up our social fabric, our world. What happens when we put kids in boardrooms, in Silicon Valley, in our marketing and accounting departments, our parliaments, and our newsrooms?

Perhaps what’s happening in arts and culture can be considered a pilot, a way to test and develop new methods of including the widespread participation of children across many other aspects of life, with the goal of evolving this new social contract, yielding changes in political, social, institutional, and cultural structures that will benefit the family, the community, the State, and democracy. In short: everything.

But first let’s talk about the kids. Just what exactly are they? What do we mean when we say that someone is a child?

What it means to be a child, and what the capacities of a child are understood to be, are not historically fixed values. Our current social order, for the most part, views children as becoming and not being. Children, we tend to believe, are moving toward a destination: adulthood. They are constituted in opposition to adulthood, and considered to be in a state of preparation for taking on life’s ‘real’ responsibilities once they are old enough, when they reach an age that is locked in law. They are on their way toward being finished. However, it is possible to conceive of young people not as headed toward a more perfected state, but as who they are right now, a view that prioritizes the young person’s being at this moment over that of the adult they may eventually become. Accepting that their being is as legitimate as anyone else’s would, ultimately, require recognizing that they do have a real stake in all discussions affecting them – and also that most issues really do affect them.

Shifting away from the psychology of development lays bare an uncomfortable fact: adults themselves hardly resemble the fully formed, rational entities that are popularly understood to be the province of adulthood. Beyond being ‘grown-up’ or just simply older, we really don’t have much of a clue about, let alone a consensus on, what it means to be an adult. Certainly to be an adult is to be many, many things we think of as childlike: vulnerable, mistaken, confused, petulant, afraid, irrational, and despairing. We never stop making missteps, learning, and growing up. But that doesn’t mean we don’t sometimes have our shit mostly together. Just like many children do.

Feminist legal scholar Martha Albertson Fineman points out that prevailing political and legal theories assume that the universal or typical human subject is autonomous, self-sufficient, rational, and competent. It is this idea of the typical human for which laws are written – laws that, for the most part, do not apply to children, who are generally not legally responsible for their actions. Therefore, the universal human subject, around whom we understand human rights and which we consider the default, is an adult. Which is to say, not a child. Adulthood produces the category of childhood; the idea of the autonomy of adults makes no sense without the lack of autonomy implied in the idea of children. We’ve seen the shape of that universal subject change, however gradually or imperfectly, to accommodate greater rights for women, racialized people, and, increasingly, trans and other gender-variant folks. And we can likewise anticipate – if not actively work toward – the dissolution of the strict binary that is adult and child.

The first step is to stop assigning essential and unchanging qualities to either adults or children. Every adult and every child has the capacities and abilities they have: some adults are more childlike than others, some require the same care that a baby requires for their entire lives, and some children are, at a young age, resilient, rational, and independent. Practically speaking, the best, safest approach to breaking down this binary may be to err on the side of caution and assume that adults, as commonly understood, simply do not exist.

We are all children, we are all vulnerable, and we are all always figuring out how to cope with complex situations in ways that will be, in all likelihood, less than perfect. In the end, the notions of childhood and adulthood are stereotypes, with all the coercion that being a stereotype entails.5 But beyond a stereotype, childhood is a way to relegate a big chunk of the population to the status of eternal other, less than and separate from the rest of us.

As a way to address this otherness, Fineman argues that we need to look more closely at vulnerability, which is ‘universal and constant, inherent in the human condition.’ She suggests we position vulnerability as central to what we think of as a typical person, contrasting it with the individual imagined in liberal political theory, where the ‘typical’ person is understood to be self-sufficient, rational, always personally responsible, and not particularly vulnerable.

Centring a vulnerable subject, like, say, a child, reveals some of the brokenness of a society ‘conceived as constituted by self-interested individuals with the capacity to manipulate and manage their independently acquired and overlapping resources.’6 Capitalism is absolutely reliant on the idea of this individual, a rational actor who trundles to the market every day to happily exchange their labour for a few dollars, the notion of the fairness of this arrangement hinging on this ideology of self-aware, rational self-sufficiency.

Fineman points to the idea of the vulnerable subject as a ‘more accurate and complete universal figure to place at the heart of social policy.’ Vulnerability is typically a condition that causes the state and other institutions to intervene in the social sphere, and using a framework of vulnerability opens things up to consider children the same way we consider adults. Imagine if vulnerability were central to our world view instead of a symbol of failure: it would become possible to shift the universal subject to include central aspects of the experience of children – which are also sure to be aspects of the adult experience. Within a vulnerability framework, every child is one of us and, as such, has the same right to participate in the world, and any systems not amenable to their participation – capitalism, say – would be considered unfair. If the universal or typical person – the vulnerable – has a hard time getting their act together to be of use to capitalism, then how useful, really, is capitalism?

‘Are you expecting children to drive cars?’ people often joke with me. But the thing is, in a few years, I don’t expect anyone to be driving cars. The world is changing so rapidly that everything is up for grabs, really, with changes to the world of work and the production of value starting to reincorporate children in meaningful ways. In fact, children and young people have, in some respects, already secured sovereign realms – spaces in which they rule, where they call the shots, set the trends, generate the wealth, and make stuff happen. Mark Zuckerberg and his crew, for instance, are constantly chasing after the kids, attempting to harness and channel the little guys’ interactions on Facebook and spinning it into wealth, and this trend is rising: think of YouTube superstars like Sabrina Cruz and Ben J. Pierce, both teens who cater their content entirely to younger audiences, or the ten-year-old kid from Quebec who goes by the name ‘Sceneable’ on YouTube. Sceneable has over forty thousand subscribers and well over two million views for his various video essays on the values of communism, the dangers of capitalism, and the compatibility of Christianity with homosexuality. The kid’s a hardworking public intellectual. In this strange world, where many adults seem to prefer childlike things – witness the staggering popularity among grown-ups of colouring books, board games, Harry Potter, and Twilight movies – and where the rules are shifting under us, children suddenly have a new kind of power, one that is particularly pronounced in the realm of arts and culture, and could be expanded upon even more, extending to other areas, where it might end up changing the game.

I’m proposing to start my little revolution in arts and culture for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the sector’s strong health. In the January 2016 Creative Industries Economic Estimates, the U.K.’s Department for Culture, Media and Sport reported that over the course of the last four years, the sector has been growing rapidly in the U.K. There is similar evidence in other areas of the world.7 In addition to offering the excitement of being involv...