![]()

Part 1

Language Learning Strategies: Theory, Research and Practice

![]()

Chapter 1

Language Learning Strategies in Independent Language Learning: An Overview

CYNTHIA WHITE

Introduction

The notions of independence, autonomy and control in learning experiences have come to play an increasingly important role in language education. A number of principles underpin independent language learning – optimising or extending learner choice, focusing on the needs of individual learners, not the interests of a teacher or an institution, and the diffusion of decision-making to learners. Independent language learning (ILL) reflects a move towards more learner-centred approaches viewing learners as individuals with needs and rights, who can develop and exercise responsibility for their learning. An important outgrowth of this perspective has been the range of means developed to raise learners’ awareness and knowledge of themselves, their learning needs and preferences, their beliefs and motivation and the strategies they use to develop target language (TL) competence. In this chapter I begin with an overview of the concept of independent language learning, and of the particular contribution of language learning strategies to this domain. I argue that a fundamental challenge of independent language learning is for learners to develop the ability to engage with, interact with, and derive benefit from learning environments which are not directly mediated by a teacher. Drawing on learner conceptualisations of distance language learning I argue that learners develop this ability largely by constructing a personally meaningful interface with the learning context, and that strategies play a key role in this regard. In the latter half of the chapter I focus on a series of landmark studies, identifying how they illuminate important aspects of independent language learning, extend our understanding of strategies and strategy development and provide insights into how students use strategies within independent learning contexts. The following three sections provide historical and theoretical background, while the two main sections in the remainder of the chapter provide a state of the art overview of language learning strategies in ILL.

The Emergence of Independent Language Learning

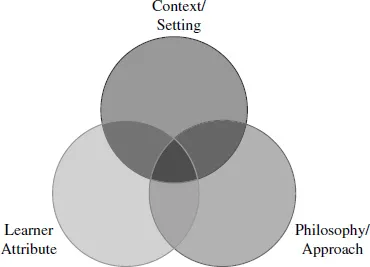

Concern for the individual learner and for learner choice, control and responsibility has been a pervasive influence on language learning and teaching for more than three decades (Brindley, 1989; Holec, 1981, 1987; Holec et al., 1996; Nunan, 1988; Rubin, 1975; Tudor, 1996), and is central to the idea and practice of independent language learning. The expectation that language learners can be independent, and that this is an important attribute and goal, underlies much of the writing on learner autonomy (Benson, 2001; Broady & Kenning, 1996; Little, 1991; Wenden, 1991), self-access learning (Sheerin, 1997), distance learning (Hurd, 2005; Murphy, 2005a, 2005b; Vanijdee, 2003; White, 2003, 2006), resource-based learning (Guillot, 1996), self-directed learning (Carver, 1984) and different forms of online learning such as tandem partnerships (Lewis & Walker, 2003). But independent in what sense? Here I explore three broad interpretations of independent language learning, the first concerning the learning context, the second outlining a philosophy of learning and the third based on learner attributes (see Figure 1.1).

Independent language learning can refer to a context or setting for language learning (Benson & Voller, 1997; Wright, 2005) in which learners develop skills in the TL often, though not always, individually. The emphasis here is on independence from the mediating presence of a teacher during the course of learning. In addition, the degree of freedom learners have to make choices (Anderson & Garrison, 1998), to select learning opportunities and to use resources according to need is highlighted. Self-access learning (Gardner, 2007), distance learning (White, 2007) and language advising (Gremmo & Castillo, 2006) represent ways of organising learning aligned to this interpretation, each of which has its own strong tradition in cultures as diverse as those of Scandinavia, the People's Republic of China, New Zealand and France.

Figure 1.1 Interrelated dimensions of independent language learning

A second dimension of independent language learning refers to a philosophy or approach to learning which aims to develop and foster independence in learners, who may or may not be in independent learning settings. Dickinson (1994), for example, argues that the most effective way of developing favourable attitudes towards independence is for teachers to prepare language learners to think about their needs and objectives and then to learn how to structure their learning. From another perspective, Candy (1991) argues that independent learning can be both a goal and a process and that the two are intertwined. Paul (1990: 37) captures both goal and process aspects, suggesting that the most important criterion for success in distance education should relate to learner independence and that ‘the ultimate challenge … is to develop each individual's capacity to look after his or her own learning needs’. This approach, promoting learner independence, has been highly influential within the learner autonomy movement (Benson, 2001). I shall shortly return to examining the relationship between learner autonomy and learner independence.

The third dimension of ILL refers to learner attributes and skills which can be acquired and used in self-directed learning, and it is here that the link with strategies and strategy instruction is most commonly drawn; independence involves developing the attitudes, beliefs, knowledge and strategies needed by learners to take actions dealing with their own learning. Independent learning in this sense is based on students’ understanding of their own needs and interests and is fostered by creating the opportunities and experiences which encourage student choice and self-reliance and which promote the development of learning strategies and metacognitive knowledge. Many learner support initiatives (see e.g. Dreyer et al., 2005) are focused on developing this dimension of learner independence. A further distinction is important here, namely the difference between disposition and ability highlighted by Sheerin (1997: 57): ‘Learner independence is a complex construct, a cluster of dispositions and abilities to undertake certain activities. It is important to distinguish between disposition and ability because a learner may be disposed to be independent in an activity such as setting objectives, but lack the technical ability – may be an independent learner in intention but not in practice …’ While ILL as a philosophy and as an attribute may both be significant aspects of particular language learning arrangements, it is useful to maintain the distinction between the two: the former emphasises the ways in which learning is configured to promote independence in learners, while the latter focuses on the contribution learners themselves make to ILL.

Within the research literature, the relationship between independence and autonomy is both diverse and contested: Little (1991) writing on learner autonomy emphasises ‘interdependence’ over ‘independence’ in learning; Dickinson (1994), associates independence with active responsibility for one's learning and autonomy with the idea of learning alone; and Littlewood (1997: 81) sees autonomy in the context of language acquisition as involving ‘an ability to operate independently with the language and use it to communicate personal meanings in real, unpredictable situations’. More recently Lamb and Reinders (2006: viii) in the introduction to their edited volume on supporting independent language learning use autonomy suggest there are ‘two strands of independence/autonomy’, one concerned with language learning as essentially an independent process, the other concerned with ways of organising learning to take place independently of teacher control. They highlight the ‘contextual nature of autonomy, and indeed independence’ (Lamb & Reinders, 2006: vii) and argue that given the complexity of the field, it is impossible to arrive at a definitive definition of either independent language learning or autonomy, echoing Aoki's (2003) argument that there are only multiple views of autonomy rather than a single authoritative characterisation. It is not unusual for learner autonomy and learner independence to be used interchangeably, as synonyms, or near synonyms (see e.g. Fisher et al., 2007; Mozzon-McPherson, 2007). Further perspectives on individual difference and learner autonomy are to be found in Chapters 2 and 3.

There have also been a number of critiques of the notion of independence and the way it has been conceptualised and applied within learning contexts. Arguing that independence implies ‘an unavoidable dependence on one level on authorities for information and guidance’ Boud (1988: 29) sees interdependence as a stage of development that transcends independence and as an essential component of autonomy. In a similar vein, Anderson and Garrison (1998) critique the emphasis placed on learner independence in distance contexts, noting that a concern with independence has not been sufficiently matched with a concern for the demands placed on learners in independent learning contexts. They posit that the goal should not be learner independence, but developing control of learning experiences by the learners themselves; this requires a combination of independence (the opportunity to explore and make choices), proficiency (the ability and competence to engage in learning experiences) and support (resources that facilitate personally meaningful learning). An important question arising from this perspective is the extent to which, in any form of independent language learning, learners can participate in and control their learning experiences, whether in terms of opportunity, disposition or ability. This question will be examined and revisited at different points in the chapter, alongside the related contribution of learning strategies.

Conceptualising Independent Language Learning: Learner Perspectives

As we have just seen, researchers and theorists have conceptualised independent learning as a particular context for learning, and as a philosophy or approach to learning including as a goal of education. It has also been interpreted as referring to qualities or attributes of learners: as skills and abilities which can be learned, developed and used in working independently and as individuals taking responsibility for their learning. These ways of thinking about independent learning tell us little, however, about how learners conceptualise independent learning and the meanings and significance it holds for them. While a substantial body of research into learner beliefs about language learning exists (Abraham & Vann, 1987; Barcelos, 2003; Benson & Lor, 1999; Kalaja, 1995; Wenden, 1986), including beliefs about strategy use (Riley, 1997; Victori, 1995; Yang, 1999), learner beliefs and representations of independent language learning remain relatively unexplored. Such a gap in our understanding is rather curious given that the purpose of independent language learning, however defined, is to enhance the learning experiences and opportunities of the key participants, the learners.

One framework for understanding the essentials of independent language learning and the critical contribution of language learning strategies comes from the learner-context interface theory (White, 2003, 2005) based on a phenomenographic study into how students perceive, experience and conceptualise their learning in an independent setting (for details see White, 1999). Within the reports of learners, independent language learning was not defined as a specific setting, or philosophy, or set of learner attributes. Rather, the essence of independent language learning involved constructing and assuming control of a personally meaningful and effective interface between themselves, their attributes and needs, and the features of the learning context. Independent language learning according to this view is based around learners as active agents who evaluate the potential affordances within their environments and then create, select and make use of tasks, experiences, and interlocutors in keeping with their needs, preferences, and goals as learners. The ways in which learners do this, and the composition of each interface is likely to differ between learners and over time. The constructed interface then guides and informs learning and develops with new learning experiences. Establishing an interface requires knowledge of self and of the environments and the skills to establish congruence between those two dimensions. The construction of the interface is also closely related to the use of learning strategies and the development of metacognitive knowledge and this is discussed in the next section.

The Contribution of Language Learning Strategies

Until the mid-1970s, a major focus of applied linguistics research was classroom-based language teaching methodology with the possible significance of alternative learning contexts or learner contributions such as motivation, learning styles and language learning strategies largely overlooked. From the mid-1970s the emphasis moved from a concern with the methods and products of language teaching to a focus on the learner, with growing inquiry into how language learners process, store, retrieve and use TL material. One dimension of this research involved attempts to find out how language learners manage their learning and the strategies they use as a means of improving TL competence. Various lists and taxonomies of strategy use have been developed as a result of these enquiries the two most influential being O'Malley and Chamot's (1990) distinction between metacognitive, cognitive and socio-affective strategies, and Oxford's (1990) Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL) comprising direct strategies (memory, cognitive and compensation strategies) and indirect strategies (metacognitive, affective and social). More recently, specific taxonomies have been produced for particular areas of language use, such as listening (Vandergrift et al., 2005) – the topic of Chapter 5 in this volume – and reading (Sheory & Mokhtari, 2001), which Chapter 4 addresses. As research in this field developed, researcher...