![]()

1 Musseques and Urban Culture

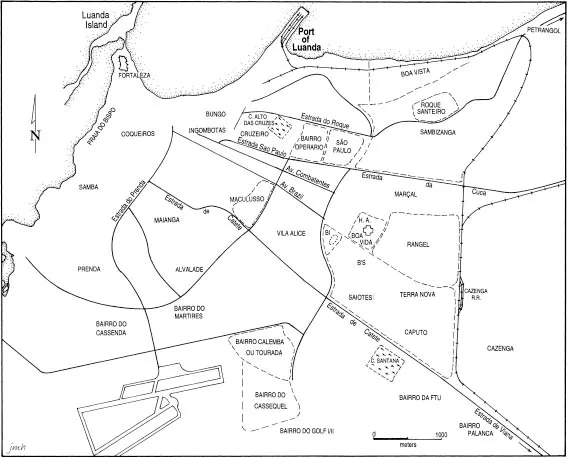

LUANDANS ASSERT AN imaginary of nation and contemporary history born of particular musseques. In casual conversations and in interviews, Luandans repeatedly offered me a meaningful map of their city. Bairro Operário was the birthplace of nationalism and the quintessence of musseque culture, Bairro Indígena (indicated as B.I. on the map of Luanda) was the home of future politicians, and Marçal was the cradle of Angolan music.1 Luandans are known for being very neighborhood-centered in their identities: where you grew up, where you live, and the neighborhood with which you identify might say more about you than your political affiliation, your race, or your age.2 And yet, the association of particular musseques with particular aspects of the Angolan nation—consciousness, political leadership, and culture—transcends individual ties. When people told me that such and such a neighborhood was the birthplace of this or that it was proffered as a national fact and not as an article of faith or a demonstration of loyalty to one’s neighborhood. Of particular import to this book is the way these casual commentaries link culture, music, and nationalism to suggest a causal relationship. The musseques were the crucible where popular urban Angolan music was created, and within and around it a sense of nation.

Alternately damned and lauded, the musseques, while on the physical periphery of the ever-growing city, have always been at the center of urban discourse and life. They are where the majority of Africans (as well as a small number of poor whites) in colonial Luanda found housing when they came to the city to enter the colonial labor market. Tracts written in the late 1960s and early 1970s by social scientists in the employ of the Portuguese government depict the musseques as peripheral urban spaces torn between the tradition, rules, and communal structures of rural life and the modernity, civility, and infrastructures of urban life. These works simultaneously reflect colonial government preoccupation with order and control (thanks to the Estado Novo’s censorial clutch), refract it through the lenses of modernization and development current at the time, and unwittingly offer a host of information inimical to colonial ideology.

Map of Luanda’s musseques, c. 1968

Based primarily on census data, police files, and information collected in interviews, colonial social science analyses sanitize the musseques. The rich histories recounted by the people I spoke with are nowhere to be found. Thus, the social science literature on the musseques is like much of the literature on urban Africa dating to the postwar period and continuing to the present in that its

tendency to project fluid, contingent, and historically-specific situations into ahistorical indicators of a permanent condition of failed urbanism effectively substitutes assertion for critical investigation and analysis. . . . [It] tends to ignore the resourcefulness, inventiveness, and determination of the countless millions of ordinary people who somehow manage to successfully negotiate the perils of everyday life.3

While keeping those limitations in mind, we cannot and should not simply dismiss colonial social science studies of the musseques. This material contains important information about who lived in these urban shantytowns, how some people spent their money and time, and what concerns the colonial administration had about them.

For Angolan writers of the colonial period who championed nationalist cultural values and political rights, the musseques symbolized the exploitation of Africans by the colonial system and the resilience of African culture despite such conditions. Like Richard Rive’s representation of Cape Town’s District Six in Buckingham Palace and Don Mattera’s descriptions of Sophiatown in Gone with the Twilight, works by Angolan writers located cultural rhythms that outpaced oppression in the musseques. They sketched three-dimensional characters where the colonial social scientists tabulated two-dimensional statistics. Along with a handful of social scientists sympathetic to the Angolan struggle for independence, they challenged the Estado Novo’s representation of itself and its history of colonization.

In this chapter I engage three perspectives on the musseques: those of colonial social scientists, those of literary nationalists, and those of social scientists sympathetic to the Angolan cause. I use the latter two to reread the former. This has three outcomes. First, it reveals a struggle over representation of the musseques. Second, by bringing the musseques into focus, it takes the next step in a modest corrective to a literature on Angolan nationalism that centers on exiled leaders, guerrilla bases, and liberated zones. Third, the interface between the world of colonial policy and ideology and the world of the musseques comes into view. Nationalist leaders, and academics in solidarity with them, overturned what they considered the Estado Novo’s flimsy cultural argument (lusotropicalism) with the hard facts of racial discrimination in colonial employment, education, and agricultural policy. But musseque residents offered a cultural riposte with a political direction. That riposte is the central concern of this book.

For the majority of Africans who lived there, the musseques were a rich cultural and social world limited but not entirely defined by the colonial order. People resident in the musseques in the 1950s through 1970s did not see themselves in the colonial social science depictions of social tragedy. Nor did they fully recognize themselves in the nationalist writers’ poesy. They had little access to either, in fact. Their memories and music tell yet another story of the musseques. Here hardship and joy cohabitate. Here urban and African co-mingled to produce the urbane. Here angolanidade was a cosmopolitan practice that led into nation instead of away from it. But first, a more panoramic view of the history of the musseques.

ORIGINS AND SOCIAL COMPOSITION OF THE MUSSEQUES

For most of Angolan colonial history, from the days of the capital’s founding in the late sixteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, Luanda’s population grew in fits and starts, and with it, the city’s boundaries and the musseques. Halting growth during the first three centuries of this period gave way to frenetic urbanization after World War II.4 Founded in 1576, the city of Luanda, on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, was the place from which the Portuguese conducted relations with kingdoms in the interior. It occupied a small space delimited by the bay on the west and rocky outcroppings to the north and south. Except for a small fishing population on the island across the bay, the area was uninhabited. Unpropitious agriculturally, it was, if nothing else, easily fortified and boasted a natural deepwater harbor. Until the independence of Brazil and the abolition of the slave trade in the first half of the nineteenth century, Luanda was first and foremost a port of dispatch in the slave trade. Africans captured in the interior were sent to Brazil as slaves from Luanda and Benguela, a coastal city further south.5 The majority of Luanda’s population in this period (including clergy and public servants) worked with the slave trade in some capacity.

With the abolition of the slave trade in 1836, Luanda’s population stabilized and grew. The city’s service sector and commerce developed accordingly.6 Luanda garnered a novel political profile: no longer dependent on Brazil, it became a significant Portuguese colonial capital in its own right. By the late nineteenth century, a creole society and mestiços (culturally mixed Africans) held sway. Mestiços occupied positions of power in government, clergy, and military.7 This new local elite expressed its self-consciousness as a group and as Angolans in the burgeoning local press.8

António Salazar’s fascist Estado Novo ascended to power in Lisbon in 1932. Salazar centralized administrative power in the metropole and reinvigorated a policy of white occupation in Angola. These policies embodied a new political agenda that spelled the decline of Luanda’s creole society and a shift in the colonial state.9 White immigration combined with a boom in coffee production to create an “explosion,” as Ilídio do Amaral described it, in Luanda’s urban growth, beginning in the 1940s and increasing in the postwar period.10 Luanda held an ever-larger proportion of the colony’s population, and the white population in particular, while the centralization of power in Lisbon circumscribed the decision-making power exercised in the colonial capital. Racial stratification intensified. By the mid-twentieth century these social distinctions were mapped onto urban geography. A series of oppositions molded local discourse—between the baixa (lower city) and the musseques (periphery), between the asphalt city and the musseques (sandy places), and between the white city and the musseques (African townships)—and described the socio-economic, racial, and cultural divisions of the city.11

Musseque is a Portuguese word deriving from the Kimbundu mu-seke which means, literally, “sandy place.”12 It originally referred to areas of the city where the asphalt did not reach. In the work of Portuguese writers and social scientists the word’s topographical meaning gave way to a sociological one, regardless of the meaning of musseque in the minds of the inhabitants.13 Some scholars claim that ever since the Portuguese founded Luanda, musseques had existed to house enslaved Africans and free laborers (along with some Europeans). With time, these places moved farther and farther away from the city center (baixa), first to Ingombotas and Maculusso in the mid-nineteenth century and then to kilometers 3, 4, and 5 on the city limits.14 Fernando Mourão points out that “plans of the city from the beginning of the [twentieth] century did not signal the existence of musseques on the periphery”; rather, huts were spread throughout nearly all city neighborhoods.15 In the mid-1940s musseques still dotted the lower city neighborhoods, such as Ingombotas, Bungo, and Coqueiros, but by the 1960s only whites and a handful of African elites continued to reside in the baixa.16 But in the context of the baixa, musseque describes a form of housing—huts—and not a place per se. When planners retrospectively applied the term musseques to conglomerations of huts occupied by African free and enslaved workers, they plied a definition of musseque that encompassed notions of labor and of race and not simply location.17 Such assumptions followed the musseques to the urban periphery.

By the mid-twentieth century, concomitant with the post–World War II population explosion in Luanda, the musseques came to symbolize, for the colonial state, all that was problematic with urbanization. Ideas about labor, race, immigration, and living conditions combined to spell pathology in the minds of the colonizers. Between 1950 and 1970 the total population of the city more than tripled in size. The number of whites more than doubled between 1950 and 1960, increasing their percentage of Luanda’s total population even though Africans continued to immigrate from the rural areas in large numbers.18 The result was more pressure on urban infrastructure in general and on Africans who were displaced to the fringes of the city to accommodate whites in the city center. Despite these intertwined processes, the colonial government and the social scientists deemed African immigration to the city, and not white immigration from the metropole, to be the main problem and the reason for the growth of the musseques.19 These outside observers characterized the musseques as disease ridden and socially addled, bursting with unemployed, underskilled young men with slack social and moral norms.

The memories of former musseque residents contrast with this image. They expressed concerns about similar issues—unsanitary conditions, unemployment, and social disarray—but ascribed them to the lack of infrastructure and not to the moral failings of the residents. In other words, they critiqued the colonial state. Residents also saw these shortcomings as part of daily life, woven into a broader context of struggles and successes related to work, recreation, and schooling.20 These were conditions in which residents lived, managed, and even thrived.

Residential construction in the musseques physically proclaimed the improvisation and innovation through which residents transformed their situation. People often built their homes from salvaged materials: hubcaps, motor blocks, and wood taken from wine barrels were all recognizable in musseque dwellings.21 Generally, walls were built of wood sticks and clay and roofs were fashioned from w...