![]()

FOUR

Kansas’s Men in Blue

IN A LETTER to his brother on April 22, 1862, George Packard complained that Kansas troops had few opportunities to fight. Instead, he wrote, “We have to march around from one place to another to quell riots, enforce law, and catch jayhawkers, while at heart we are all jayhawkers.”1 Packard’s complaint captures the frustration many soldiers felt—having joined the military to suppress the rebellion, Kansans were far from the front and often engaged in law enforcement and antibushwhacker raids. To men eager for action and adventure, these tasks scarcely seemed different from everyday life on the frontier.

While little regular action took place within the state itself, Kansas troops were dispatched along the state’s borders. Occasionally sent north to Nebraska, they were more often occupied combating guerrilla activity along the border with Missouri. In addition, Kansas troops were sent on significant expeditions into Indian Territory to the south. Overall, Kansas’s nineteen regiments and four batteries served both near and far from home. To the south, these soldiers served in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee. They fought under Ulysses S. Grant in the Vicksburg campaign and under William Rosecrans at Chickamauga. Kansas’s troops also were dispatched to the West: participating in the New Mexico expedition, serving in the mountains near Denver, providing escort duty for trains and railroad workers, protecting telegraph lines, building forts such as Fort Halleck in Dakota Territory, and, of course, fighting American Indian tribes resistant to continued American westward movement.

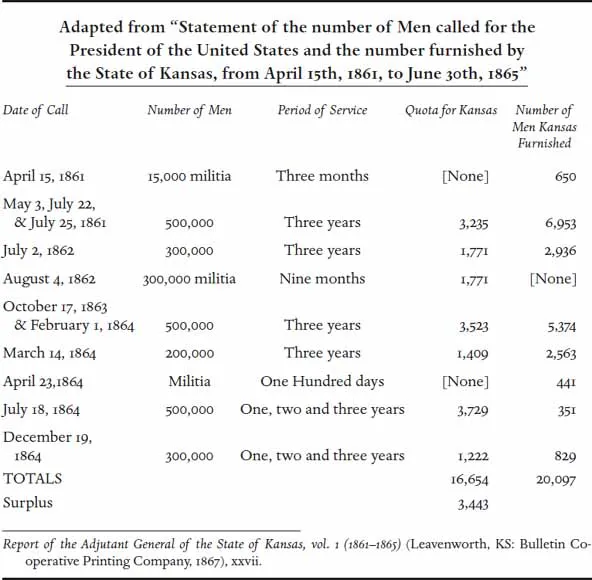

Ultimately, Kansas furnished 20,097 men for the Union. Although this number may seem paltry when compared to states like New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, each of which furnished more than 300,000 men for the United States, Kansas had a small population in 1860. According to that year’s census, the state had 107,206 inhabitants, of whom 58,806 were white males; of these, 32,921 were of military age (between fifteen and forty-nine years old). As such, the ability of the state to produce more than twenty thousand men to serve is remarkable in and of itself. But the sacrifice these Kansans made to preserve the Union is equally noteworthy.

Kansas had the highest mortality rate (deaths in action and from wounds) of any state in the Union. The general ratio for all states was an average of 35.10 deaths per thousand men, but Kansas had a mortality rate of 61.01. The state with the second-highest mortality rate was Massachusetts, with a rate of 47.76. Overall, Kansas suffered 8,498 casualties. Of these, 1,000 men died through combat: 796 were killed in battle while 204 later perished from the wounds they sustained. However, while war is always deadly, in this era disease commonly claimed more lives than did battle. Chaplain Hugh Fisher of the Fifth Kansas Regiment, for instance, wrote to the governor that there were “not 20 men among us who have not been sick at sometime during our stay” in Arkansas, and that to remain in the area would “disable and destroy us without gaining a victory for our armies in our country’s cause.”2 Indeed, disease felled more than double the number of men killed in combat, taking 2,106 of Kansas’s men. In addition, almost another 2,000 men had to be discharged because disability rendered them unfit for duty.

Although an individual’s risk of death depended largely on the vagaries of war, there was one general exception: soldiers well understood that African Americans fighting in the South were at greater risk because they would likely be killed rather than held as prisoners of war. Indeed, when assessing the combat deaths of Kansas troops, this proves true for soldiers in the First Kansas Colored Infantry, which had significantly higher deaths than other Kansas troops. For instance, 4 of its officers were killed, along with 156 enlisted men. The regiment with the second-highest number of deaths was the First Kansas Infantry, which lost 11 of its officers and 86 of its enlisted men. Overall, the highest deaths from disease came from the Fifth Kansas Cavalry, which, having served in Arkansas for more than two years, lost 219 men. Finally, the regiment with the greatest number of desertions was the First Kansas Infantry, with 238 deserters. This rate of desertion is comprehensible when one considers that the First Infantry lost the second-highest number of men in combat, lost the most men to death from the wounds sustained in battle, and, with 209, had the most men discharged because of disability.

Kansas recruited sufficient men that a draft was not ordered until December 19, 1864. However, when notified of the order, Kansas governor Samuel Crawford argued that the state had not been appropriately credited for all the men it had supplied the Union. The issue of properly crediting solders was complicated. For instance, the 1860 census found only 627 African Americans in the territory, but it furnished 2,116 men for the First and Second Kansas Colored Regiments. Although most of these individuals were from Arkansas and Missouri, Kansas received credit for their service. However, the three Indian regiments Kansas raised (including one in Indian Territory) had not been properly credited. Thus, Crawford went to Washington to convince Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to reverse the draft call. He was successful, but Stanton was so lax in officially relaying the news that Crawford arrived home to discover that a number of Kansans already had been drafted and sent to St. Louis. Although ordered released, these men served in the Tenth Kansas until that regiment was mustered out, in July 1865.3

In addition to these troops, a number of Kansas men served in the militia. Governor Thomas Carney was especially keen to raise Home Guards to protect the border, but was denied permission by President Lincoln. Ultimately, Carney authorized 150 men to patrol the border, funded by $10,000 of his own money (later reimbursed by the state). But after the 1863 Lawrence massacre, more attention was paid to the state’s security needs. By the time rumors of Sterling Price’s impending invasion of Missouri and Kansas circulated, in late 1864, the state had ten thousand militia, eight thousand of whom were serving along the border.4

Ultimately, Kansas provided the Union with a contingent of troops that seems small when compared to other states’. Yet Kansans were on the forefront of change, raising diverse troops that included not just white men but African American and Indian men as well. Moreover, as the following documents attest, Kansans joined the fight to preserve this nation’s integrity and Constitution in numbers that exceeded government requests. As with any group, the expectations and experiences of the soldiers varied considerably. Some were eager for combat and were disappointed to find themselves serving close to home. Others were appalled by the behavior of the officer corps and the morals of those with whom they served. Sent into the South, many Kansans found the seasons difficult to withstand and the leniency with which the rebels were treated confounding. Well aware that Kansas was underpopulated and lacked the men and arms necessary to defend the state, most expressed concern for those left behind. And many, meditating on the changes war wrought, likely agreed when George Packard wrote his brother that while he intended to go home after the war, it would not “be the young ‘fop’ that left” so many years before.5

KANSAS EXCEEDS ITS QUOTA

Kansas’s contribution of more than 20,000 men to the Union cause is particularly impressive given that its 1860 population included only 32,921 white men of military age. Ultimately, Kansas exceeded its quota by almost 3,500 men.

A WISCONSIN SOLDIER MOVES THROUGH KANSAS

Aiken J. Sexton, a private from Company E of the Twelfth Wisconsin Volunteers, was one of many soldiers traveling through Kansas on the way to the war front. Sexton wrote his wife, Catherine, about conditions in the state.

Leavenworth City Kansas Feb 26/62

Dear C

. . . I did not know there was so much diferance in the wether of Wis and this country We have seen no winter here the coldest days I could work in my shirt sleaves the weather for three weeks back has been warm and pleaseant the frost is mostly all out of the ground and the farmers begin to make preperation for their springs work the ice is braking up in the river in two days more it will be open. it is very muddy except the highest places and there the roads are getting dusty; our reg is still quartered here except co F and B. They are detached from the reg and sent to Kansas City distance thirty five miles our co is comfortably situated here with plenty to eat. We draw more rations than we can eat we buy a good many extras with our over rations. We drill now four hours a day two hours in the forenoon and two in the afternoon the reg is getting pretty well perfected in their drill We are not afraid to drill before any of them they say here we beat anything they ever saw for the chance we have had I tell you there is military men here military men of all rank from the highest to the lowest at the fort is stationed a large boddy of regulars whose term of enlistment is five years they are daily enlisting more to make up the regular army. This place is a lively one the most of the business is Government business. yesterday there was a train of forty wagons left here for Fort Scott loaded with pourk and flour for the army. . . .

Ever the same

A. J. Sexton

Fort Scott Kansas Mar 17/62

Dear Catherine

. . . this part of Kansas is thinly settled all the settlements there is is along the streams and they are far between it is a good farming country here the only trouble is market they have no regular market to the nearest point to the Mo River is one hundred miles and that is their market at present. . . . We have considerable guard duty to do it takes twelve a day to guard the camp ground and town if there is any extra guards wanted co E is the co they call on the Captain spoke to the Colonel about it he said co E shouldrs was broad he said they was the healthyest co on the ground and the largest. that is so our co is the largest and the best drilled . . . there is none of our co in the Hospital I think our reg is favored with good health in comparison to the Kan Regt they have buried from one co four a day with the measles their doctor says they have been to free with those fancy women which invest these Southern towns. that disease and the measles together is pretty sure death it seems to bad to see men throw away them selves in that way when perhaps they have Fathers and mothers or perhaps we who mourn their loss if loss they might call if I were them I should consider it no great loss. . . .

Direct Fort Scott | A J Sexton |

Miscellaneous Sexton Collection, Kansas State Historical Society.

EXCERPTS FROM JOSEPH TREGO’S LETTERS

Joseph Trego came to Kansas Territory from Illinois in 1857. Settling in Sugar Mound, Trego and some compatriots constructed and operated a sawmill in town. A member of the Fifth Kansas, Trego saw action in Missouri and Arkansas. In these letters, Trego candidly assesses the officers and reveals how soldiers worried for those they had left at home.

Camp No 1 en route to M. City

Aug. 13th 1861

Dear Wife,

We have been under orders to march South, for several days but were delayed from day to day by difficulty in getting what was required. Lane has reported everything on hand and in readiness for his brigade but we did not find it so and have not been able to get a start until yesterday after dinner. . . .

It will require us to wait where we are—5 miles from Leavenworth—until the remaining can be loaded. We have 21 government wagons with us loaded with provisions, arms, uniforms and camp equipage, and when the freighting wagons are all together and drawn by six pairs of oxen, and numbering seventy five—we will be ready for another move. We will not, I think, reach Mound City before the middle of next week. The 75 wagons are loaded with provisions for Lyon’s forces. . . .

Your affectionate H

Fort...