![]()

SIX

Bushwhackers, Jayhawkers, and Prisoners

In August 1863, General Thomas Ewing Jr. had had enough of the guerrilla warfare that was raging across western Missouri. Ewing ordered that any citizens giving aid to William Clarke Quantrill and his men were to be arrested. Ewing soon detained thirteen women in the makeshift jail in Kansas City, Missouri. Among the detainees were Mary, Martha, and Josephine Anderson, sisters of notorious bushwhacker William “Bloody Bill” Anderson. When the building collapsed on August 14, killing four of the women and severely injuring many others, Quantrill’s raiders vowed revenge. They chose as their target the city of Lawrence, Kansas, long a stronghold of free-state sympathizers and the home of Senator James H. Lane. Just after dawn on August 21, Quantrill and 450 men attacked the city, murdering between 140 and 190 men and boys in cold blood. They looted and burned most of the buildings, robbed the bank, and left behind a scene of horrific destruction.1

Newspapers around the country reported the massacre, prompting Ewing to strike again at bushwhackers and their supporters in the countryside. On August 25, 1863, Ewing issued General Order No. 11, which commanded everyone living in Jackson, Cass, Bates, and Vernon counties, as well as several other areas, to vacate their homes within fifteen days. The order did not discriminate between loyal and rebel farmers; all residents were to leave. The purpose of the order was to make it impossible for guerrillas to survive in the western counties of Missouri by removing any potential local support. In reality, the displacement resulted in widespread suffering. Many families—mostly women, children, and elderly people—fled to the larger towns, creating a serious refugee problem.2 Moreover, because the order provided for the confiscation or destruction of grain supplies, the refugees (who included both Southern sympathizers and loyal Unionists) suffered from shortages. Although some charitable aid societies, including the Western Sanitary Commission, donated food and supplies to those living near the large cities, many of the thousands of people who had fled their homes had to live on government aid. The artist George Caleb Bingham was so outraged by what he considered to be the oppressive severity of General Order No. 11 that he was moved to paint his famous protest Martial Law, or Order No. 11, depicting the hardships wrought by the evacuation.3

Throughout 1863 and 1864, the violence continued to escalate despite the wholesale evacuation of the western counties. On September 27, 1864, Bloody Bill Anderson launched a horrific attack on Centralia, Missouri, looting and burning. Anderson’s men murdered twenty-two unarmed sick and wounded Union soldiers who came in on a train, scalping some of them. In some parts of the state, 1864 brought the worst bushwhacking violence of the entire war. Men and boys were murdered, and women were often the victims of personal insults and abuse, especially if they were suspected of pro-Union sentiments. A number of black women suffered physical assaults and rape.4 While the guerrillas distracted federal forces, General Price determined to take advantage of the conditions to attack St. Louis.

On September 19, 1864, three divisions of Confederate Missourians led by Joseph O. Shelby, John S. Marmaduke, and James Fagan, comprising more than twelve thousand men, entered southeastern Missouri from Arkansas. Their long-term goal was to capture the St. Louis Arsenal and, if possible, the city itself. Price’s men had been conducting raids into Union territory for the past year and gathering valuable intelligence. He hoped that his raid into Missouri would also bring thousands of new recruits into his army. By mid-September, some of his men had reached Pilot Knob, where they fought a bloody battle with Brigadier General Thomas Ewing’s force of about fifteen hundred troops. Union artillery was able to hold off Price’s force, but by the evening of September 27, Ewing began to realize that he would not be able to withstand Price’s superior numbers much longer. Muffling the sound of the wagon and caisson wheels with blankets, he slipped out of the fort, blew up the powder magazine, and secured the depot at the train station. Ewing had lost about 250 men (killed, wounded, missing, or captive), and Price more than 1,000.5

In the end, Price’s plan to raid St. Louis failed, as well. Following the time-honored tradition of concentrating on capital cities and other vital geographic objectives, Price turned his attention to Jefferson City. Capturing Missouri’s capital, he believed, would give him control over the entire state. The 1864 gubernatorial elections were approaching, and a victory at “Jeff City” might have allowed the Confederates to put acting Confederate governor Thomas C. Reynolds into office. But Price was disappointed by the very low turnout of recruits. Rebellion fever had burned out in central Missouri, even as Price was slowly making his way toward Jefferson City. General William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Department of the Missouri, reinforced Jefferson City with 16,500 men, leaving the surrounding countryside vulnerable to the guerrillas. Families packed up their children, their livestock, and their belongings and fled into the nearby woods.

The Confederates skirmished briefly with Union defenders at Jefferson City, but soon moved westward toward the Kansas border, through Boonville and Lexington, where they skirmished again with pursuing Union forces. At Boonville, Price met briefly with Bloody Bill Anderson and then headed for Kansas City. By the end of October, however, Anderson had been killed in an ambush. Price began a hopeless retreat back into Arkansas, during which General Marmaduke was captured and most of his army and weapons were lost. The last battle between organized military units in Missouri occurred on October 27, 1864, when a small Union force under the command of General James Blunt caught up with General Jo Shelby’s command of Price’s army near Newtonia, Missouri.

Bushwhacker violence continued until long after the war was over, though much of it was unconnected with political or military goals. In the end, the most notorious guerrillas died as they had lived: violently. Bloody Bill Anderson was killed in an ambush in 1864, and Quantrill, who fled first to Texas and then to Kentucky, was shot a year later. The few bushwhackers who survived the war surrendered to civil and military authorities. The James brothers and other former raiders, notably Cole and Jim Younger, would turn bank and train robbers in the late 1860s, but some of them (especially Frank James) reformed and settled into a staid old age.6

MARY ANN CORDRY TAKES THE OATH OF LOYALTY

I, Mary Ann Cordry, of Cooper Co, Missouri, do solemnly swear that I will bear true allegiance to the United States, and support and sustain the Constitution and laws thereof; that I will maintain the National Sovereignty paramount to that of all States, County or Confederate powers; that I will discourage, discountenance, and forever oppose secession, rebellion and the disintegration of the Federal Union; that I disclaim and denounce all faith and fellowship with the so=called Confederate Armies, and pledge my honor, my property, and my life, to the sacred performance of this my solemn oath of allegiance to the Government of the United States of America. Subscribed and sworn to before me, this 21 day of May 1863.

C. S. Moore,

1st. Lieut. and Ass’t. Provost Marshal.

Mary Ann Cordry [signature]

Union

Description: Age 43, Height 5 7, Color of Eyes Grey, Color of Hair Aubun, Characteristics [blank.]

Copy.

Cordry, Alphabetical Files, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis.

GENERAL ORDER NO. 11

General Orders,

No. 11

Hdqrs. District of the Border,

Kansas City, Mo., August 25, 1863

I. All persons living in Jackson, Cass and Bates Counties, Missouri, and in that part of Vernon included in this district, except those living within 1 mile of the limits of Independence, Hickman Mills, Pleasant Hill, and Harrisonville, and except those in that part of Kaw Township, Jackson County, north of Brush Creek and west of the Big Blue, are hereby ordered to remove from their present places of residence within fifteen days from the date hereof. Those who, within that time, establish their loyalty to the satisfaction of the commanding officer of the military station nearest their present places of residence will receive from him certificates stating the fact of their loyalty, and the names of the witnesses by whom it can be shown. All who receive such certificates will be permitted to remove to any military station in the district, or to any part of the State of Kansas except the counties on the eastern border of the State. All others shall remove out of the district. Officers commanding companies and detachments serving in the counties named will see that this paragraph is promptly obeyed.

II. All grain and hay in the field, or under shelter in the district from which the inhabitants are required to remove, within reach of military stations, after the 9th of September next will be taken to such stations and turned over to the proper officers there, and report of the amount so turned over made to district headquarters, specifying the name of all loyal owners and the amount of such produce taken from them. All grain and hay found in such district after the 9th of September next not convenient to such stations, will be destroyed.

III. The provisions of General Orders No. 10, from these headquarters will be at once vigorously executed by officers commanding in the parts of the district and at the stations not subject to the operation of paragraph I of this order, and especially in the towns of Independence, Westport, and Kansas City.

IV. Paragraph III, General Orders No. 10, is revoked as to all who have borne arms against the Government in the district since the 21st day of August, 1863. By order of Brigadier-General Ewing:

H. HANNAHS,

Acting Assistant Adjutant-General.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, ser. 1, vol. 22, pt. 2 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1888), 473.

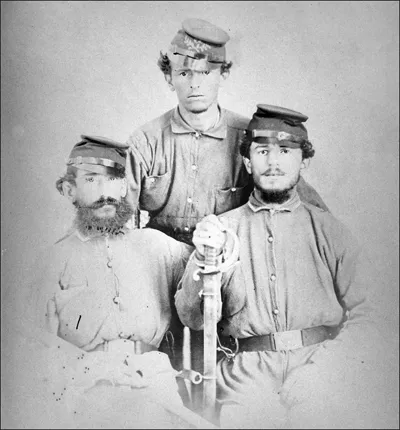

Alexander Hequembourg (seated, left) with two unidentified soldiers. Alex Hequembourg (18301911), served in Co. B, Fourth Regiment, United States Reserve Corps; became Captain of Co. G, Missouri Engineers; and served in the Fortieth Missouri Infantry under General John Schofield. He fought at Vicksburg, Franklin, Nashville, Mobile Bay, and at First and Second Bull Run. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society

GENERAL SCHOFIELD COPES WITH THE AFTERMATH OF GENERAL ORDER NO. 11

August 26,1863

Received by telegraph first report from General Ewing of the burning of Lawrence, Kansas, and murder of its Citizens by Quantrell. Informs me that he has ordered all people to leave the border Counties within fifteen days, when he will move all forage and provisions from those counties. Says he has written me explaining the reasons for the order. I reply that his order coincides nearly, with one, the draft of which I sent him yesterday for his consideration. Genl. Ewing calls for more troops….

Radical papers keep up a senseless howl about the conservative policy of the present Administration in Missouri. They willfully ignore the fact that my policy a year ago, and at present, was and...