![]()

1

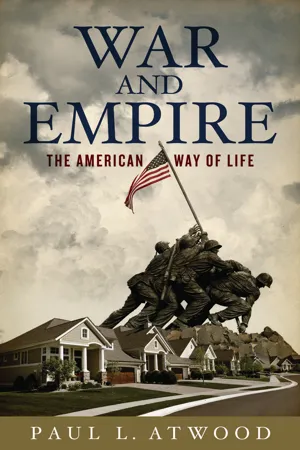

Introduction: American Ideology versus American Realities

How many Americans have ever paused to consider that the United States has never bombed any nation that could bomb us back? Ponder the ‘Good War’. Neither Germany nor Japan was remotely capable of devastating American cities during World War II, as the US assuredly desolated theirs. If they had possessed such capacity we would never have bombed them for the same reason we never bombarded the Soviets. Since neither of the Axis allies wished war with the US (for the simple reason that they didn’t believe they could win), and neither could cross the ocean to attack our cities, neither constituted a genuine military threat to the US. In Chapter 7 we shall examine the real danger officials perceived, and how the administration of Franklin Roosevelt manipulated events such that both Germany and Japan would view America as the primary threat to their imperial aims, and therefore opt for war as their only possible insurance, thereby enabling the US to enter a war the public had decidedly not wanted. But would Roosevelt have chosen war, as he surely did, had he believed that a majority of our cities would lie in ruins? Of all belligerents the United States lost the fewest lives by far. Would decision-makers have been willing to accept civilian casualties on a scale like Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima, or even London during the Blitz? The strategic goal of American elites in World War II was to expand their global power and reach, taking advantage of the ruin and decline all the other combatants would suffer, enemies and allies alike. The US waged war in such a way as to rise in the global hierarchy, not to sink, and it rose to the top.

Certainly there were American casualties in all wars but never on the scale faced by the losing side. None of this is to dishonor those who gave or risked their lives. Most believed what their officials told them about the threat to the nation. In all cases officials who opted for war believed material gains would far outweigh the loss of life since the war makers would not be risking their own, or in most cases, their kin’s.

Or consider how the US approached its communist enemies of a generation ago and ask the same questions. Though the US falsely blamed both the Soviet Union and China for the wars in Korea and Vietnam, and for resistance to the US throughout the so-called ‘Third World’, American bombs were never unleashed on either of them, though American ordnance lay waste to Korea and Indochina. The reason is quite elementary. The communist giants had nukes and could incinerate us. We ravage only those who lie all but helpless before us.

I challenge any who disagree with the foregoing to name a single American war, with the exceptions of the Revolution and War of 1812, in neither of which Britain brought its full might to bear, where the opponent came close to matching the wealth, resources, and military power the US threw against it. Could any of the following have despoiled our own territory? Iraq? Afghanistan? Serbia? Panama? Nicaragua, Vietnam? Cambodia? Laos? Dominican Republic? Korea? Spain? The Philippines? The Sioux? The Cheyenne? Mexico? The Cherokee? Both Germany and Japan were the strongest enemies the US ever faced in battle, but let us note whose cities were reduced to rubble at the close of that war, and whose were not. The US emerged from World War II with the fewest casualties, its continental territory unscathed, and richer and more powerful by far.

I’m not aware of any scholarship that attempts to quantify the number of civilians killed by the US in its many wars. The figure must be in the millions though many policy-makers, military strategists and arm-chair generals would undoubtedly claim that most such civilians were victims of the misfortunes of war – ‘collateral damage’ is the current newspeak on the subject. But in many cases the killing of helpless civilians was deliberate. Tokyo, Hiroshima, Nagasaki? General Curtis LeMay insisted there were no such thing as civilians in Japan but one of his principal lieutenants, later Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, has admitted that had the US lost the war he would have been tried as a war criminal. Pyongyang? Hanoi, Haiphong? ‘Free fire zones’ across South Vietnam, killing and maiming the very people we were supposed to be saving? Cambodia, Laos, Belgrade, ‘Shock and Awe’ Baghdad, Falujah? And we mustn’t forget the many hundreds of thousands killed by Washington’s clients who received advanced American weapons and who were given tacit permission for wholesale murder in places like Indonesia, Chile, Argentina, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Congo, Angola, Lebanon and Palestine, even Iraq when Saddam Hussein was our man in Baghdad. For a people outraged at the murder of our civilians on 9/11 we are morally anesthetized when it comes to admitting the crimes our own actions, votes and tax dollars have wrought.

A survey of the American past indicates beyond any doubt, and only with the exception of the British during the earliest years of the Republic, that the US has consistently waged warfare always by choice and only against foes that could not win. The romantic fantasy surrounding the Revolutionary War and War of 1812 ignores the fact that the British did not project their full power because they were tied up with more powerful foes in Europe. If they had dispatched their best troops instead of numerous mercenaries the outcome would have been quite different. Washington, Jefferson, Franklin et al. would have swung from the gallows. Since that era the US government, and American public opinion, has always claimed, in all wars, that it was the enemy that initiated hostilities, to which the inherently peaceful American people were honor bound to respond in order to defend ourselves, to restore justice, and overcome ‘evildoers’. But this is simply false. Enemy attack of one kind or another was always the justification for war, but in all cases the preconditions, indeed pretexts, for war were set in motion prior to actual combat. American wars have always been matters of choice, not necessity.

Today, less than a generation after the Cold War ended, the United States is at war again, in Iraq and Afghanistan, and is threatening to attack Iran and Pakistan. Of the 191 states comprising the United Nations, the US has military bases in 140 of them. American arms patrol all the seas and skies, including outer space. The Pentagon declares flatly that its strategic agenda is to achieve nothing less than ‘full-spectrum dominance’ over any potential foe of the future. While many American officials wring their hands about nuclear weapons proliferation, those same public ‘servants’ believe that the US is justified in constantly upgrading its own nuclear arsenal and missile systems, dismissing the real fear that others have about this. Nor is much made of the hypocrisy of condemning violations of nuclear proliferation in Korea, Pakistan or Iran, while condoning, and even aiding, them in Israel or India.

Much media commentary about the policies of the Bush Administration insists that all this is a perverse departure from the traditional American values and ideals that are claimed to have been in play since the founding of the Republic. But that is a self-serving fantasy fortifying our national conceit that we are a people apart, exceptional and singled out by God or Destiny to redeem humanity. The template for current policies and war was set even before the Founders rose in rebellion against their government. While many of them used powerful rhetoric to exclaim about natural rights and liberty, they only meant such to apply to ‘natural aristocrats’, like themselves. Their primary goal was to replace their masters in London, to reap the riches of the American continent themselves, thence, as the motto on the dollar proclaims, to establish ‘a New Order of the Ages’.

The American enterprise began in savage violence against the peoples Europeans encountered on this continent. The US itself was brought forth by martial exploits glorified and celebrated every Fourth of July, and its vast territory was wrested from others by pretext, aggression, extreme brutality, genocide and ‘ethnic cleansing’. Since the US emerged from World War II as the most potent nation in history we have slaughtered millions, directly or not, the vast majority being helpless civilians. In the requisite patriotic storyline, we congratulate ourselves as apostles of peace, compromise and conciliation, and insist that our grossly uneven campaigns are evidence of national heroism mounted against evil.

Mass public acceptance of hypocrisy on this scale requires a deeply-rooted rationale for explaining to ourselves why we can commit naked aggression and not have to experience the guilt or shame which we insist others should feel when they act similarly. In sum, Americans possess a highly adaptive ideology that provides ready-made justifications for our actions, and reproaches for those who oppose us. At bottom the American ideology claims to adhere to a morality that defends self-determination universally for all. But that assertion is honored mainly in its breach.

Humans tend to take their idea systems for granted, descended as if from heaven, not paying much attention to how they have developed, what purpose they serve, who transmits ideas in whose interest, or how they’ve been acculturated to accept them as given. In all cases, the predominant ideas that circulate, that are allowed to circulate, are the ideas of the dominant members of any given society, and they justify or rationalize the privileges, advantages and interests the system gives them. So long as any given system works well enough for most of the population a level of stability sustains the status quo.

Americans pretend not to be subservient to set dogma, believing ourselves to be utterly pragmatic and utilitarian; that is to say, non-ideological. We even contend to be anti-ideological when we oppose the claims of communists or jihadists, yet refuse to believe that we ourselves are captives of an idea system that colors our every perception and renders us incapable of seeing the world as it really is, much less seeing ourselves as others see us. That belief system has developed and evolved over the 400 years since Britain erupted from its slim borders. Inheriting ideas and methods from British empire-building, the US eventually surpassed its parent in scope and method.

The American idea system, which justifies and explains the economic and political system, has evolved incrementally, with each stage building upon earlier suppositions derived originally from Britain itself. No radical break occurred as was the case with the French, Russian or Chinese Revolutions. Both the American and British polities evolved along a similar trajectory. From the beginning in the US a self-selected and tiny elite spoke of ‘We the people’ and ‘democracy’ but actually feared popular rule, and created two-tiered political institutions designed to thwart it, much like their model, the British Parliament. The system of profit known as capitalism has always been claimed as the only engine of economic and political activity that can rationally meet human needs. Though the communist world was condemned for its ‘slave system’, we breezily dismiss the fact that the American system at its inception was built on the backs of the dispossessed and enslaved, or people in other conditions of servitude, and is today proclaimed as the culmination of human political evolution. More than 150 years ago, during America’s bloodiest war, Abraham Lincoln declared that the US was ‘the last, best hope of mankind’. More recently, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright averred that ‘we are the indispensable nation’. For some time now humans in most ‘advanced’ civilizations have regarded themselves as the crown of creation. Today Americans believe they are the apex of human social evolution.

At every stage of American development key ideas circulated widely to rationalize the circumstances and policies of the day. Actions, often brutal, revealed true motivations. At the dawn of British colonization, Protestant and Puritan religious ideas portrayed a ‘New Canaan’, a new land endowed to a new ‘Chosen People’. The early republic advanced ideas already prevalent in England, borrowed in part from the study of ancient Roman texts, about the rights of citizens and balanced government, although ancient certainties that only an aristocracy should rule were also retained. By the mid-1800s religious ideology merged with what was claimed to be ‘scientific’ racism in the doctrine of ‘Manifest Destiny’, avowing that the rapid spread of Anglo-American civilization across the entire continent was evidence of God’s approval and blessing upon the United States. By the turn of the twentieth century, with massive demographic shifts and industrialization utterly transforming the social landscape, the national ideology proclaimed that the American way of organizing society was the most advanced the planet had ever witnessed, and called for the world to open its doors to American capital. At the start of both World Wars I and II, as economic collapse threatened the very foundation of the American system, the nation promoted itself as the savior of democracy, pitted against the forces of aggression and militarism, utterly discounting the means by which the US has always wielded its power.

We shield ourselves from such unpleasant truths by imagining we have created this most materially prosperous society by virtue of our own industry, creative genius, work ethic and our exceptionally humane national character. We fantasize that if nations or peoples remain ‘undeveloped’ and mired in poverty, it can only be because they are slothful, or uneducated, lacking in drive or ambition, or otherwise benighted. Others see more clearly. As an African student of mine once put it, angering American students in the process, ‘With what are we to develop? We have been plundered of our very people and resources for five centuries for the sake of your development!’

The reality is that the United States has become an empire, an empire different in certain respects from others. But just as all empires before it, the American model seeks to enrich itself by exploiting the peoples over whom it rules.

In 1789 upon leaving Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin, who had presided over the Constitutional Convention, was asked what the 55 men inside had accomplished. His answer was terse and succinct: ‘A republic if you can keep it!’

Like the other Founders, Franklin was well aware of the slim history of self-governing peoples. In all cases, institutions of representative government, from ancient Greece to Rome to the Italian republics of the Renaissance, had decayed owing to corruption and had devolved into dictatorship. Old Ben was not optimistic about the chances for the newest republic. Rome had once been a functioning republic with popular institutions to safeguard the rights of citizens, but for a full century before an emperor assumed the throne these had been collapsing as the hunger for more land and treasure and the armies to procure these became the principal preoccupation, first of the ruling classes, then of the plebs. Even the imperial dictatorship was circumspect enough to retain the outward symbols of representative government like the Senate and tribunes of the people, in order to foster the illusion that civil rights were still intact. But Rome was increasingly ruled by the sword and by imperial fiat.

The same fate is now befalling the United States. Every president since World War II has engrossed the powers and perquisites of the office. Congress is but a debating society doling out treasure to its corporate benefactors, chiefly banks, insurance giants, oil corporations and military contractors. Bit by bit the Bill of Rights erodes before our eyes with measures like the Patriot Act eroding privacy rights and the prohibition against unwarranted searches. American ‘popular’ culture (manufactured from above) is little more than videonic ‘bread and circuses’, the imperial Roman practice of distributing food to the masses when unemployment rose too steeply, and allowing them entry into the chariot races and gladiatorial combat in the arenas, in order to let off frustration that might have led to riots. If ordinary Americans oppose the current wars they do so for the most part only tepidly because we are a people, like others, who prefer the guise of fantasy to reality. We have the most bloated civilization and lifestyle ever seen on planet earth and we know, if only by keeping this forbidden knowledge just below our consciousness, how we got to this state, and whom we had to kill. And we do not want our globalized cornucopia to cease providing its fruits. If the resources we need to sustain our conspicuous consumption happen to be in other people’s countries, if their labor is cheaper in order to provide the goods, then history obliges us to do what the Romans did. And we do.

The United States was born amidst war, slavery and genocide at the dawn of the Age of Empire. The American system of production and allocation required unpaid or cheap labor and began with outright plunder and annexation of other peoples’ land. That system has evolved to deal with domestic inequality, mal-distribution of wealth and political instability by continually enlarging the pie, at the expense of others. Though elites remain firmly in control of power and own or control the vast bulk of resources, enough surplus is generated so that, with significant exceptions, the American system has been able to include vast sections of the middle and working classes in its material bounty and rewards, but always because others had to die or be dispossessed. As long as the American economy does not allow extreme poverty and unemployment to rise above a certain threshold and affect the largely white middle class, it has generally had at least the passive support of a majority, except when the inherent defects lead to recession or depression. But the prism of ideology has always filtered out much in the larger spectrum of reality. We refuse to believe that the American way of life is, and always has been, the way of war, conquest and empire. We refuse to believe that many Americans enjoy bloated, wasteful lives by wreaking havoc upon others, and because we have promoted our own model of industrial development as the zenith of human progress we have inspired or induced other nations to follow the example, thus inflicting mayhem upon the very biosphere itself. We could, if we were honest, dub ourselves the culture of spoliation.

To be sure there are some who will say that throughout the human condition it has always been thus. History would seem to agree. But we Americans are in profound denial of the extent to which we are not exceptions to this arc of history. Thus, any serious hope or prospect for peace in the twenty-first century must frankly confront the indisputably bloody history and present policies of the most potent armed entity ever to bestride the planet. And then, or else, we must begin to live up to the ideals and professed values we claim and teach small children.

Most are taught that the American Revolution was necessary to right the intolerable injustices the British had visited upon their colonial subjects. Yet analysis of the financial interests of the principal Founders indicates clearly that they stood to gain far more by being rulers than the ruled. Their rhetoric of freedom certainly was not applied to the majority of Americans, including most white men who were not allowed to vote. The Declaration of Independence decried the ‘slavery’ that British rule had imposed upon the likes of Washington, Jefferson and many others but manifestly excluded the real slaves. No sooner had the infant US come into existence than it set out immediately to replace the former mother country as the ascendant power in the entire western hemisphere, more than once attempting to wrest Canada too. It waged war against the Spanish and the French to acquire the lands they claimed, and then against the indigenous peoples over whom the empires alleged to reign. In the most rapid territorial expansion in history the US transited the continent ‘from sea to shining sea’, piling up a mountain of corpses along the way and trailing millions of slaves in their wake.

By the middle of the nineteenth century the southern slavocracy’s desire to exploit more land for the profits generated by unpaid labor dovetailed with the northern industrial-financial elite’s longing for the ports of Los Angeles and San Diego. The problem was that these lands belonged to the newly independent nation of Mexico. So the dark art of pretext was employed, as it would be so many times again, and Mexico was charged with violating American territory, whereas exactly the reverse had occurred. The result was that Mexico lost almost half of its land and the US augmented itself by about one-fourth.

Now a Pacifi...