This is a test

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

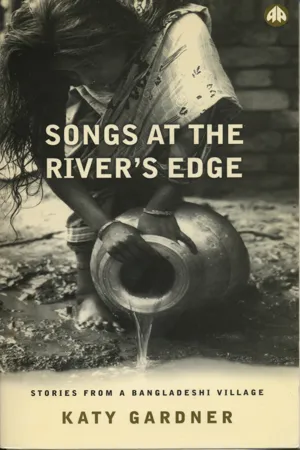

Katy Gardner's account of her fifteen-month stay in the small Bangladeshi village of Talukpur has become a classic study of rural life in South Asia. Through a series of beautifully crafted narratives, the villagers and their stories are brought vividly to life and the author's role as an outsider sensitively conveyed in her descriptions of the warm friendships she makes. Above all Songs at the River's Edge is written from a deep respect of Bangladesh and its country.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Songs At the River's Edge by Katy Gardner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias biológicas & Ciencias en general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 SEPTEMBER – ARRIVAL

I arrived in Talukpur one September night, as crickets chanted and jackals screeched to each other across the fields. The moon had already risen high and bright over the still water, and the lanterns had been lit for hours: we had been expected before sunset, but we were late.

We had left Sylhet Town, in the north-east of Bangladesh, early that afternoon. We were a curious party – a middle-aged man with smart town trousers and an officious-looking briefcase with nothing in it but a newspaper; an elderly lady with a missing front tooth and kindly eyes, buttoned up in her all-concealing burqua (long cape with veil) and clutching a small packet of betal nut and pan leaves for the journey; and one over-tall, over-shabbily dressed foreigner with a sweaty face and strange Western jewellery. This stranger obviously had no idea of how to carry on: she did not even have the grace to shield herself from the astounded stares of passers-by with her mud-splattered brolly.

I had met Mustak, my escort, through a local development organisation, and it was to his village that we were going. He was a liberal, who had read widely and educated himself far beyond the usual boundaries of the village. Now he worked and lived in the town, with his young wife and children. Because of this, perhaps, he had hardly batted an eyelid at my professed desire to ‘live in a village for a year’, and with great efficiency he arranged somewhere for me to stay. The old woman was his distantly related aunt. She clutched my hand and blinked at me in a friendly way as we jolted through the chaos of Sylhet traffic, hunched up together under the rickety canopy of the rickshaw. I understood that she was a close relative of the family with whom I was to live, that her name was Kudi Bibi, and that was about all.

It was the first rural night I had seen. The journey from Sylhet Town to Talukpur, the village where we were going, took about five hours, and by the time the road ran out, and Mustak had found a boatman to punt us across the flooded fields, the day was already fading. We drifted all afternoon through the flat green Bangladeshi countryside which spreads out endlessly until it meets the enormous sky with its vast blueness and billowing clouds. The river pulled us for hours through the scattered villages which lined its bank; past endless homesteads, with their scattered buildings and yards and their hayricks spilling into the water; past women washing pots, and listless cattle which chewed their suppers and looked stupidly across at us. Rows of waddling ducks quacked uproariously at the sight of the boat. On and on we went, until the water turned inky and the sky was suddenly filled with swooping bats and the flicker of glow-moths. Bangladesh is never still, and nights are never quiet. Instead, the countryside roars with life: a million insects singing in the dark, and a million human voices calling and muttering and yawning and praying as the lamps are lit. As the boat splashed and creaked through the water we passed others, sometimes containing solitary silent women with their veils down and their faces turned away, but more often workmen in their bamboo hats singing at the tops of their voices about lost love or the greatness of their saints, as they disappeared almost completely into the dark. All along the horizon were continual flashes of electricity and the distant rumble of thunder, even though the sky was clear.

After seemingly endless turns in the river, our decrepit wooden boat glided round a corner, and then at last I was told: ‘That’s it! We’re here …’

The boat turned towards a clump of trees. Within them was what would be my home for the next fifteen months. We slowly approached the land of the bari (homestead), which in this, the wet season, had become an island in the monsoon waters. I could glimpse buildings through the greenery; there was no sign of light or, for that matter, life. But then with a crash a door swung open, and a lantern appeared. I could hear excited voices shouting out to each other, and see figures hurrying towards us.

The boat struck land with a jolt. The figures now had faces, and were growing into a crowd. For a moment I sat in the boat clasping my bags and facing the people as they came nearer. More than anything, I wanted to turn round and go home. In that short second, I was terrified. And likewise, the people coming towards me must have had their fears: they had volunteered their hospitality to me, but they did not know what problems I, a young woman from the West, might bring them. If I was scared by their unfamiliarity so, no doubt, were they by mine.

So we stood momentarily facing each other, on two sides of a cultural divide that I was hoping would not last.

Then the moment ended and the silence was burst with a babble of words. My bags were taken from me by a gaggle of small boys, and numerous hands helped me step out of the narrow boat. An old man stood apart from the crowd, smiling humorously and shouting directions at the boatman. Several girls grinned shyly and giggled when I tried to say the Islamic greeting: ‘Salaam-e-lekum.’ A rounded, pretty woman with a worn face and broken spectacles took me firmly by the arm and guided me through the slippery dark yard towards the buildings. I thought I heard the word ‘Amma’ (Mother) – but maybe not. Friendly voices told me things and asked me questions, none of which I understood. With a practised hand, another woman pulled the orna (long scarf) I was wearing across my chest, up, and over my head. Everyone laughed. It was the first small gesture in a long process of helping me to become like them. The material felt uncomfortable over my hair, but I tried to stop it from falling off.

This was really it, then. I had arrived.

Arrivals are nothing special in Talukpur, for these days they happen all the time. As the villagers found themselves part of Pakistan, and then suddenly part of the newly created Bangladesh, their community expanded and events in the outside world increasingly intruded into their lives. A war of independence was fought, and in Dhaka presidents came and went. The infant Bangladesh lurched from hope, to coup, to famine; to more coups, cyclones and floods. People stopped being so optimistic, and began to plan ways of escaping from the poverty which so often surrounded them. Back in Talukpur, too, villagers looked beyond their own small patch for their futures. For several generations there had been a tradition of young men travelling to Calcutta to find work on ships which took them all over the world. Many had stayed on in Britain and America, coming home only for brief trips before returning for more work in the factories and restaurants which were helping to make some of them rich back in their villages. Now, the trickle became a steady flow. In the 1960s the British government encouraged men from Commonwealth countries all over the world to provide a cheap labour force for its expanding domestic economy, and thousands of men from Talukpur, and the other villages around it, left for the industrial cities of Britain. Others went to the Middle East to work on building sites, or as street vendors, or in all manner of jobs which they did not talk about when they got home. Their wages helped their families to get by.

So over the years the village had been tied to the outside world by many fine threads which wrapped their way around it, and pulled it with them. On the surface, nothing had changed very much. The rice was planted each season, and after it had turned from bright green to the gold of harvest time, teams of scraggy bulls were used to plough the land. The rains came, and as the fields filled with water the men would spend their days fishing from them, bringing home pots filled with shrimps and fish. Women still hid from strangers and in public usually covered their faces with veils; marriages were largely still arranged and the rulings of the elders held. But these days, too, paths had been built, and big launches carried passengers from the local villages towards the road. People could move more easily around the countryside. More of them had travelled on buses or in cars, more had visited Sylhet, and more could read and write. Talukpur still had no tarred road or electricity, but as the accoutrements of the modern world edged slowly closer, as year by year the lines and bridges were extended, everyone was well aware that, Allah willing, they were coming. Arrivals, then, be they of new ideas, new goods, or new people, were not really anything special.

As for me, I was to make the journey to the village many times, although never in such style as that first September night. As the waters receded and the paths dried out, I discovered that I could walk the five miles from the road across the fields, and – give or take the perils of the odd bamboo bridge (one pole to walk along, with another usually extremely rickety one at an angle to cling on to) – get home with far more ease than in a cramped and soggy boat. Best of all was during the driest part of the dry season, when I could take a rickshaw right into the village. This was ideal, for as time wore on and I became more versed in local attitudes, and aware of how outrageous my behaviour was, I developed a dread of walking alone. I hated being stared at as I passed through villages which lay on the path to Talukpur, and loathed hearing the snatches of excited conversation which rose up in small gusts whenever I appeared:

‘Who is she?’

‘Where’s she going?’

‘Look, she’s alone!’

‘Hey, Beti [lass], is there no one with you?’

The worst option was to take the launch from the river a few miles away to the Dhaka road, ten miles down river. To get on the boat involved jostling over planks perched precariously above thick, fetid sewage, and then cramming myself into the women’s cabin, which was invariably filled to bursting with hot women chewing betel, and children sucking at ice-lollies or vomiting over their mothers’ saris. I could never sit in that cabin and not curse the men. That they had a vast cabin to themselves on that launch, and had condoned the rules which meant that we women were herded together like cattle to avoid the shame of being seen by them, made me want to spit. The flexibility to different people’s customs, which I had never found difficult when travelling through a country, soon disintegrated after staying put in Bangladesh for more than a couple of months, and never was I more of a cultural bigot than when I was sitting on that launch. I am ashamed to say that at those times, when men bunched around the open doorway of the women’s cabin to gawp at me – deciding, no doubt, that since I was alone and Western I must be fair game – I forgot all about cultural relativity and tolerance. The groups who peered and whispered and giggled at me often became the astounded objects of my wrath, stunted and badly expressed as it was:

‘What are you staring at? Don’t you have any shame? Go away! I don’t like this at all!’ I was apt to cry when my patience ran out altogether.

When I eventually arrived in Talukpur I would recount these exchanges to the women in my family, who would hoot with laughter and then say: ‘But you can do this. We could never say such things …’

Talukpur was a very typical village, if there is such a thing. It was surrounded by fields, and divided by a small river which ran through it. In the dry season this turned into pasture-land; in the monsoon it swelled with water and carried great cargo boats laden with bricks or clay pots, sailing boats, and small private boats with bamboo cabins through the village. At one end were a few tea-stalls and ‘tailor shops’, which were actually just stalls where men sat hopefully with sewing machines. There was a mosque and a madrasa, where a small group of young men learnt to recite the Qur’an. Most of the villagers were Muslim, but not all. At the edge of the cluster of homesteads, and beyond the tea-stalls, was a large gathering of mud-and-straw buildings. This was the bari of the village Hindus, all of whom were members of the fisherman Patni caste. About two miles away, nearer the Kustia River, was a large bazaar where the men shopped for things which the village did not produce itself. At lean times of the year some families even had to buy in extra rice. It was perhaps smaller than some villages, and certainly the area was richer than most other parts of Bangladesh, but there was nothing so very special about it.

The family led me inside the buildings of their homestead. Unlike the poorer houses of most of rural Bangladesh, their home had been built with sturdy concrete, and ornate flowers and an inscription in Arabic had been painted on its front. Although my newly adopted family owned only an average amount of land, they had relatives abroad, and many years ago the earnings sent to them from Britain had been spent on the new house. But despite the solid walls and ostentatious appearance of the bari, inside it the floors were made of packed earth, and the walls were bamboo.

We went through the main part of the building where the men slept and the grain was stored, and into the small room where I was to live. I knew how lucky I was to have so much space to myself – everyone else slept five to a bed, or more. But the beds were huge, and as I was told many times, sleeping alone is a scary and unhappy situation: my solitude was not envied. In the flickering lamplight I could make out my own hulking wooden bed, which took up most of the space, a table and a wooden clothes-stand. It was perfect.

With great hilarity my possessions were unpacked and examined, which at least gave us all something to do and to laugh about. The things I had bought in Sylhet – a hurricane lamp and a mosquito net – were closely examined and put away. Then the table in my room was laid for me to eat, and enormous bowls of rice and fried fish, vegetables and mutton curry, were placed on it. The food was delicious. Although as I settled in such lavish meals were no longer provided in my honour, and I ate normal meals with the family, my appetite for village food never waned.

Lastly, I was taken down to the pond by a small group of giggling children for a wash underneath the stars, and then locked into my tiny little room, with reassurances that this way, with the wooden slats of the window tightly closed and the door barricaded, the night bandits (whom everyone feared greatly, but who never appeared) would have slightly less chance of getting at me. I was exhausted from the long journey, but my mind was buzzing with excitement. I changed into the longest, and thus most respectable nightdress that I had been able to find in Dhaka, and climbed into bed and under my mosquito net. Within two minutes I decided that I would probably suffocate, but when I stuck my head outside for air, the mosquitoes descended with glee. Sweat was dripping from my back and it had begun to rain once more. I could hear the slow mumbles of my newly adopted father’s prayers and sleepy female voices from the kitchen area. It was my first night in Talukpur, the start of a different life and a brand-new beginning.

I was woken the next morning at four-thirty by the distant sound of the azan (call to prayer) and Abba (Father), who had taken his cue from the cries across the fields and was mumbling his prayers. It was barely light outside, but the crickets had stopped chirping and a cock began to crow. A gleam of pink light appeared over the tree tops which surrounded my room. I could hear doors bang and people hawk as they greeted the day with a globule of spit.

I was more than slightly nervous at the prospect of my first day in the village. I knew I would be showered with attention, and would probably be alone only when I went to the latrine. As it turned out, I was accompanied even there. Huge crowds would gather wherever I went and I would be the object of close scrutiny and comment for months. I steeled myself, and climbed out of my mosquito net.

I had come to Talukpur to learn, and the villagers were to be my teachers. After the end of that first day it was obvious to everyone that we had a lot of work to do. With me, they were going to have to start with the basics.

‘You’re just like a baby,’ one of the family sisters said that evening. I was pleased to have understood what she’d said, a rare occurrence in that first week, but not quite so flattered at the content of her words. First, I had to try and sort out just who was who in my adoptive family. Luckily for me, the bari had only two households; some in the village had as many as nine, the members of which would probably have taken me light years to untangle. Even these two, though, confused me for days, especially the task of sorting out just which children and babies belonged to whom. Head of our household in practice, if not in name, was Amma, a wonderful woman with a proud nose and mouth, sturdy arms, and black bushy hair tied in a knot at her neck. This was cut short to keep her head from overheating, a dangerous condition associated with sickness and mental problems. Although she would have laughed at the notion, Amma was beautiful. She had a large, soft, extremely strong body which had borne twelve children, and strong, wise eyes which had seen four of them die. She padded around the bari tending her vegetable plots, cooking, making mats, fans, clay hookahs, and whatever else was needed, and generally being the pillar of the family. Throughout my stay she would regularly come to me and sigh heavily, declaring how terrible everything was: how they couldn’t give me good food; how they were so poor; and how she spent every minute of her days worrying over me and praying for my comfort. I soon learnt the appropriate answers to these little speeches and realised that they were her way of showing affection, and I was not meant to take them entirely seriously.

Then there was Abba, who spent his days surveying his fields and saying his prayers. Abba must have been about sixty. He was apt to wander into my room and tell me the names of the British royal family or instruct me on the mistakes which Christian doctrine made compared to the truthfulness of Islam, shake his head, declare ‘You’ll never understand’ and then disappear back to his hookah. Every afternoon he changed into his best lungi and punjabi shirt and, with strict instructions from the women on what to buy, set off with his walking stick to the bazaar, a short walk of about two miles across the fields.

There were four daughters, and with the comings and goings of the elder married ones and their children, the household was in constant flux. One of them, Minera, lived in the bari next door. She was married to her cousin, and because she was so close she spent much of her time with us. Another, Saleya, had come back from her husband’s village several miles down river to give birth to her fifth child. Then there were Najma and Bebi, the two unmarried daughters, still at home although their school days were long over. Najma had been educated up to class ten, a rare achievement for a village girl, and acted as teacher for the bari children outside the short and irregular hours of the small village school. Her lessons consisted of standing over her small brothers...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. September – Arrival

- 2. The Lives that Allah Gives

- 3. Hushnia gets Married

- 4. A Woman’s Place

- 5. The Lives that Allah Takes

- 6. Roukea Buys a New Sari

- 7. Stories of the Spirits

- 8. Storms

- 9. Abdullah Seeks a Cure

- 10. Alim Ullah goes to Saudi

- 11. Ambia’s Story

- 12. November – Departure

- Glossary