![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A DOOR, SLIGHTLY AJAR

The ascendance to power of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers (Nazi) Party in 1933 exacerbated a European Jewish refugee crisis that had begun with the close of the First World War. Jews living in Germany and German-occupied territory were faced with few options. Some, especially youth in the tens of thousands, had the good fortune to find new homes abroad. A paltry number were able to immigrate to Canada, which accepted fewer Jewish refugees than any other nation in the western hemisphere, including the Dominican Republic.1 Canadian immigration policy and policy makers had a distinct anti-Jewish bias, and allowed only 5,000 Jews to enter the country between 1933 and 1947.

This chapter tells the story of the earliest European Jewish refugees admitted to Canada and their experiences of resettlement and integration. Those experiences later established the framework for the subsequent absorption, resettlement, and integration of the waves of postwar Holocaust refugee survivors to embark upon Canadian shores.

Canadian Jewish Life

Canadian soil gained its first permanent Jewish settlers in the latter part of the eighteenth century, more than one century before Confederation. Comprising primarily German- and British-Jewish immigrants abandoning the United States for professional opportunities in the underdeveloped North, small Jewish hubs sprouted up in Lower and Upper Canada (present-day Quebec and Ontario), typically in close proximity to water with quick access to the larger and more established American Jewish communities. Communal institutions, including synagogues and cemeteries, sparingly followed. In 1882, an estimated 1,300 Jews permanently resided in Canada. This figure rose dramatically between 1882 and 1914, owing to a mass exodus of Jewish immigrants from the Pale of Settlement, a region of Imperial Russia occupying much of present-day Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus, and western Russia. Jewish residents in the Pale, the largest ghetto in recorded history, experienced economic, social, and legal restrictions, living according to 1,400 legal statutes and regulations that controlled all aspects of Jewish life. Laws dictated Jewish occupations, places of residence, and movement; obscene taxes on religious life, down to Sabbath candles, contributed to the debilitating poverty under which much of the population subsided. As a further assault on Jewish traditional life, community leaders were mandated to present young male recruits, aged twelve to twenty-five years, for twenty-five-year military terms.

Life deteriorated further following the March 1881 murder of Czar Alexander II in St. Petersburg by revolutionaries belonging to the Narodnaia Volia, or the “People’s Will.” Despite the fact that only one Jewish woman revolutionary—Gesia Gelfman—participated, Jews were blamed for the assassination. Reprisals began immediately. Jewish communities across the Pale lived in fear of pogroms, or orchestrated acts of anti-Jewish violence, for sixteen months. Jewish homes, businesses, and synagogues were destroyed, men were beaten and slaughtered, and women subjected to public rapes.2 Anti-Jewish regulations known as the May Laws, enacted in 1882 in response to the pogroms, coupled with utter poverty and lack of opportunity, prompted the migration of nearly two million Jews to Western Europe and North America, including Canada. In 1914 alone, approximately 20,000 Eastern European Jews arrived in Canada primarily from present-day Poland, Russia, Romania, and Galicia—the single largest number of immigrants from one ethnic group in Canadian history. More than 150,000 Jews called Canada home by 1929.3

Immigration of “undesirables” came to a halt after the First World War. A newly instated emphasis on immigrant applicants’ ethnic backgrounds challenged the prevailing policy, which had supported immigration as a means to populate and till the Prairie provinces. While British and Northern European candidates were preferred, the previous policy emphasized numbers, not creed. Post–First World War policy suggested that non-British immigrants possessed inferior moral and ethnic characters, posed a literal risk to Canada’s economy, and challenged the nation’s health.4 Immigration officers and the Canadian public made no efforts to mask their racist attitudes.5 By the mid-1920s, ideology transformed into action with the official instatement of ethnically selective immigration restrictions.

And yet despite these restrictions, Canada’s Jewish population continued to grow, reaching 155,614—or 1.5 percent of the country’s total population—in 1931. With the exception of agricultural colonies in the Prairies, Jews were concentrated primarily in the urban centres of Toronto, Montreal, and Winnipeg. Montreal counted 48,724 Jews in its 1931 census, representing 5.9 percent of the city’s total, while Toronto ranked slightly behind with 45,305 persons, or 7.2 percent of the total. Winnipeg represented the third-largest Jewish centre, counting approximately 17,000 Jewish residents in 1941.6 The Jewish community grew slowly over the ensuing decade, to 165,000 in 1939. Canadian Jews were loosely divided into two groups: those who were well established and integrated, having migrated prior to 1900; and the masses of working-class, Yiddish-speaking Jews who had emigrated from Europe only a generation earlier.7

German, British, and American Jews who had immigrated to Canada prior to, or separate from, the Pale Jews represented a numerical minority among interwar Jews. Through linguistic, cultural, and ideological differences, prosperous Jews and their newly arrived co-religionists were separate entities with limited overlap.8 Eastern European transports observed laws of kashrut and Orthodox observance to varying degrees.9 Conservative synagogues gained momentum only in the 1930s, and Canada did not share the dominant German-Jewish tradition of Reform Judaism present in the United States. Younger generations’ commitment to traditional and seemingly insular ways of life declined. Devotion to religiosity waned due to practical factors, such as the need to work on Shabbat and high cost of kosher food, as well as the influence of political ideology and contemporary attitudes about integration and secularism.10

Integration efforts aside, Jews experienced increasingly insidious forms of anti-Semitism through the 1930s. Discriminated against in education, employment, and housing, and subject to stringent immigration restriction, their capacity to sponsor relatives and landsleit in politically unstable Europe collapsed.11 Anti-Semitic fervour reigned in Quebec, home to the most sizeable Jewish community in the interwar years.12 Quebec Catholics’ hatred was rooted in Jewish theology, while French nationalists recognized Jews as the “embodiment of the anti-French.”13 Both parties considered Jews inherently threatening. Interwar Jewish life in Quebec was most often conducted in English. Quebec Jews were perceived as aligned with Protestant English Canada, whose language, culture, and political ideologies challenged that of the French.14

Québécois anti-Semitism was fostered by community leaders and absorbed by the masses. The “father of French Canadian nationalism,” Roman Catholic priest Lionel Groulx, also an active political leader and intellectual, regarded himself a rabid anti-Semite.15 Abbé Groulx founded the journal L’Action Française in the early 1920s to increase awareness of provincial politics among francophone youth. He also acted as the public face of L’Action Nationale, a nationalist organization promoting French Catholic independence from English Canada’s social, economic, and political arenas. Groulx publicly blamed English Canada, and particularly its Jewish actors, for all societal woes affecting Quebec, applying a lethal combination of Catholic anti-Jewish liturgy and contemporary Judeo-Bolshevik ideology to denounce the Jewish presence in Canada.16

Beyond Groulx’s manipulation of Catholicism’s anti-Jewish doctrine, French Canada was also gripped by popular Nazism and fascist ideologies transported from Europe. Montreal-based journalist turned rabble-rouser and Hitler-enthusiast Adrien Arcand established the anti-communist and anti-Jewish Christian National Social Party (Parti National Social Chrétien) in the mid-1930s. In 1938, Arcand took the helm of the National Unity Party of Canada, an amalgamation of his Québécois party and the Nationalist Party of Ontario, itself a product of the “swastika clubs,” minor Nazi-inspired anti-Semitic groups that arose across the country. Arcand espoused his racist and anti-refugee sentiments through several weekly French-language newspapers and magazines, including L’Action Française, Le Goglu, and Le Patriote. Images of the “savage Jew” participating in the blood libel, and more contemporary conspiracy theories of world domination by the “Jewish race,” abounded in the papers’ pages.17 Arcand’s party achieved nominal success in provincial (Quebec) elections and held seats in the national assembly. The leader’s 1941 arrest as a Nazi sympathizer, and subsequent detention in a New Brunswick internment camp, dictated the collapse of the National Unity Party.18 Arcand’s legacy persisted, continuing to influence anti-refugee and nationalist sentiments into the postwar period.19

Anti-Semitism and nativism in Canada were never limited to Quebec. The Social Credit Party of Alberta operated as an expression of the die-hard nationalism of the anti-foreigner beliefs of its British founder and engineer, Major Clifford Hugh (C.H.) Douglas.20 During the Great Depression, Albertans suffered from a dramatic decline in agricultural production (its primary economic market) and mounting farm debts. The virulently anti-Semitic Social Credit’s popularity was enmeshed in the regional and national political, social, and economic landscape of financial woes, and traditional nativist ideologies. Banking systems purportedly managed and owned by wealthy capitalist Jews became the party’s focus of all criticism. The party’s first leader, Baptist pastor William Aberhart, presented an identifiable scapegoat for their political and economic ills: the international Jewish conspiracy.21

Aberhart instructed party officials to disseminate anti-Semitic sentiment in newspapers and especially through radio broadcasts—practices similarly employed in the Nazi state. Aberhart and his peers distributed copies of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the most famous fabrication of anti-Semitic propaganda produced in turn-of-the-century Russia, in civic centres and churches. The party’s popular newspaper, the Canadian Social Crediter, featured hateful serials like The Land for the (Chosen) People Racket, which blamed Jews for nationalization of land, and the Programme for the Third World War, which posited that international Jewish conspirators were planning world domination.22 The distribution of racist literature ended only with Ernest Manning’s restructuring of the Social Credit Party in the postwar decade.

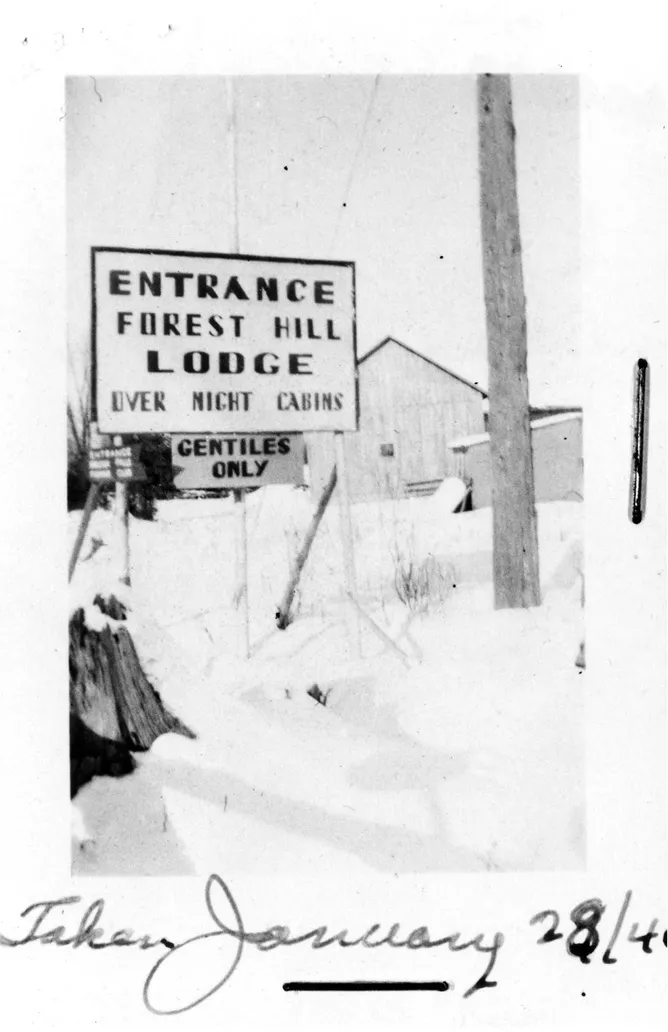

Communities in English-speaking Canada faced more genteel but equally damaging anti-Jewish sentiment. Prejudicial messages streamed through media and spiritual congregations. Quotas on Jewish enrolment in university faculties persisted into the postwar period, limiting the professional aspirations for those with the intellect and financial means to meet institutional standards.23 Jews who successfully penetrated the walls of academia encountered obstacles on the path to professional lives. Most recognized the social prejudices and ventured toward self-employment in medicine, law, dentistry, and mercantilism in an effort to avoid the omnipresent “gentiles only need apply” advertisements.24 Few bothered considering careers in politics, engineering, or academia. But discrimination did not stop with employment. Legislated racial profiling deterred Jews from purchasing land in desirable Anglo-Saxon upper-middle-class neighbourhoods.25 Socially, Jews were also unabashedly excluded from enjoying “gentile only” beaches, country clubs and other recreational facilities, and hotel properties.26 Such restrictions protected gentiles from unnecessary social interaction with Jews while simultaneously, if unintentionally, strengthening Canadian Jewry’s internal organization and infrastructure.

Despite the ubiquitous anti-Jewish prejudices and nativist undercurrents plaguing interwar Canada, anti-Semitism rarely culminated in violence in English-speaking provinces. The riot at Toronto’s Christie Pits the night of 16 August 1933 constituted an infamous exception to this rule. Fighting exploded at a baseball game when youth members of the local swastika club unveiled a flag bearing a swastika. The predominantly Jewish opposition team responded to the provocation. Italian Canadians stood alongside their Jewish neighbours. Extreme acts of violence took to the streets, and continued throughout the night. Miraculously, no one died.27 The riot served as a warning: while Canadian Jews did not live under the oppression of Hitler’s Germany, their presence and livelihood stood under an omnipresent shadow of anti-Semitism.28 Canadian Jews needed a central representative body to speak on their behalf.

1. Gentiles only sign, Forest Hill Lodge at Burleigh Falls, Ontario, 28 January 1940. Ontario Jewish Archives, fonds 17, series 5-3, file 64, item 1.

Organizational Life

The interwar period saw an exponential growth in Jewish organizational life. There were three central forms of organization: landsmanshaftn, Zionist parties, and Jewish labour unions. Landsmanshaftn, or benevolent societies, composed of individuals originating from a town or region in Eastern Europe, flourished across North America in the first half of the twentieth century.29 Landsmanshaftn assisted newcomers in practical matters and most frequently conducted operations in Yiddish. Groups served as free loan societies and provided members’ access to physicians, cemetery plots, and emergency aid. Zionist organizations also abounded in the early 1900s; the arrival of European Jewish immigrants brought both traditional and radical versions of Zi...