- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

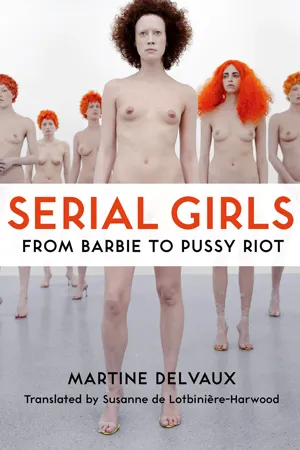

Everywhere you look patriarchal society reduces women to a series of repeating symbols: serial girls.

On TV and in film, on the internet and in magazines, pop culture and ancient architecture, serial girls are all around us, moving in perfect sync—as dolls, as dancers, as statues. From Tiller Girls to Barbie dolls, Playboy bunnies to Pussy Riot, Martine Delvaux produces a provocative analysis of the many gendered assumptions that underlie modern culture. Delvaux draws on the works of Barthes, Foucault, de Beauvoir, Woolf, and more to argue that serial girls are not just the ubiquitous symbols of patriarchal domination but also offer the possibility of liberation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Serial Girls

“It’s a girl!” cries the doctor upon seeing the newborn – a performative act sealing her identity. Welcome to this world! From now on, you will be a girl.

It’s a Girl is the title of Evan Grae Davis’s 2011 documentary about femicide, the quasi-systematic elimination of girls. Millions of girls mistreated, neglected, kidnapped, raped, murdered … killed or left to die. According to the U.N., two hundred million girls are missing throughout the world today.1 A silent war against girls.

One day, while reading a magazine article, I come upon a dialogue between a mother and her daughter. The girl asks, “Mom, what is a girl?” The mother answers, “A girl is somebody who won’t remain one for very long.” I came upon this dialogue when my daughter was five years old, and one evening, as my hand reached to turn off her bedroom light, well tucked into her little bed, she asked, “Mom, is it true that some people hurt children?” My daughter is ten now. She is becoming what we call a young girl. I ask myself what that actually means….

I read Gaddafi’s Harem, a book by Le Monde journalist Annick Cojean.2 In it, she describes the underside of Muammar Gaddafi’s regime: his harem of girls kidnapped from their families to become his sex slaves. Gaddafi was well known for making room for women in his organization – everyone knows about his famous Amazon bodyguards and how he made them the standard-bearers of his revolution. Each of these guards possessed an identity card. Last name, first name, photo, and the following inscription: “Daughter of Muammar Gaddafi.” Bodyguards and “whores,” these women were the Guide’s daughters; they were forced to call him “Papa Muammar.” After his death, hundreds of boxes filled with Viagra were discovered in each of his residences.

Cojean’s investigation rests in part on the testimony of a girl named Soraya, kidnapped at fifteen and put into Gaddafi’s service. She recalls the following scene:

I saw countless wives of African heads of state go to the residence, though I didn’t know their names. And Cécilia Sarkozy as well, the wife of the French President – pretty, arrogant – whom the other girls pointed out to me. In Sirte, I saw Tony Blair come out of the Guide’s camper. “Hello, girls!” he tossed out to us with an amicable gesture and a cheerful smile.3

Reading Cojean’s book,4 what catches my attention is Tony Blair’s greeting, his clearly trivial “Hello, girls!” I imagine the scene in my head. I wonder whom he is speaking to, and whom he is talking about at that moment. I tell myself that not for a second does he wonder who they really are.

That’s when I hear a variation on the title of Primo Levi’s celebrated testimony If This Is a Man, written after he left Auschwitz. I hear that phrase, which is neither a question nor a claim – rather a request, an appeal: “Consider if this is a man.”

And so, the obvious: Consider if this is a girl….

What is a girl? How are girls made, and how do they make it through life? How do they untie the corset, the straitjacket, how do they breathe oxygen into the doll’s body? How do they make leaps, come alive, jump, run, take on the street? How do they scream, live, write?

In the following pages are casts of girls as seen everywhere, in reality or in our imaginations, girls we sometimes no longer even see anymore. Harems, stables, teams, gangs, groups, cohorts, troupes, collectives, communities, series of girls that say a lot about what it means to be a girl.

The figure of serial girls is a hypostasis,5 a first principle stating that girls are girls because they’re serial girls. Which is to say that girls are essentially serial – that a girl is a girl because she is part of a series, as in: girls, the girls, the Gilmore Girls, the Spice Girls, the Guerrilla Girls, showgirls, girls’ night out, a gang of girls…. True, men also receive their share of “boys”: the boys, the boys’ club, a gang of boys…. But the label “boys” does not refer to age, nor does it infantilize those it describes.

Boys is not a term that aims to devalue those to whom it is attributed; rather, it intends to name a group of which men are a part and within which they socialize. It is a title having to do with masculine-gendered identification in a general and positive way and doesn’t concern the way in which sexuality is lived. However, the story is quite different when it comes to the term girls.

Writing in the eye of the hurricane of the feminist revolution, Marina Yaguello, in Les mots et les femmes (Words and women),6 has this to say about the word girl:

We say a girl or a loose woman, but not a loose man…. The word girl is also pejoratively connotated (to “visit the girls,” i.e. a whorehouse; “street girls,” i.e. hookers), while the word boy is completely neutral. Girl is in itself a term of abuse…. Even more so when applied to a boy: “You’re nothing but a girl!” The status of “girl” being undesirable, a girl will be called a “tomboy”, but a boy will never be termed a “tom-girl”…. And why has the French word garce, the legitimate feminine form of garçon, used in the Middle Ages without any pejorative connotation, since the 16th century, come to mean girl of ill repute, then cow, then shrew, then bitch.7

Girl is what happens between little girl and woman. In a patrilineal society, it’s what remains between “her father’s girl” and her husband’s name. If, throughout time, the category “girls” has played upon both virginity (in the sense of “maiden”) and exacerbated sexuality (in the nineteenth century, for example, girls meant those working in brothels), it is because girls remain in a state of non-propriety, of perpetual non-belonging…. Hence the fact that they have come to adopt this “surname,” girls, attributed to women as a positive site of identification (in the same way that other populations experiencing discrimination have reclaimed certain insults, such as queer and nigger). Inside this temporal and social parenthesis, be it real or artificial, resides the possibility for resistance.

Here, Simone de Beauvoir’s words, which radically changed our way of thinking about gender, come to mind: One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman. “What is a woman?” asked de Beauvoir in The Second Sex, finding an answer in the very fact of asking the question: “A man never begins by positing himself as an individual of a certain sex: that he is a man is obvious.”8 Woman, said de Beauvoir, is defined not by her own self, but by and in relation to him/man. She is a relative being. “He is the Subject; he is the Absolute. She is the Other.”9

In this sense, there is an important difference between serial girls and the boys’ club: masculine identity does not depend on the club that the man belongs to. The boys’ club comes after masculinity and reinforces it. Men socially organize among themselves, sharing identities that are already constituted. Thus, the boys’ club does not produce masculine identity; it is, rather, the result of an identity.

Thus, for the purposes of this chapter, I will say that, generally speaking, the masculine exists, without preamble or justification; it simply is. Whereas the feminine (and this is my working hypothesis) relies, at least partly, upon the figure of serial girls. Serial girls is the locus that makes it possible to discover the feminine. Serial girls is not about shaping girls as they are; it is about shaping girls into what we want them to be.

What do these images say, these images of female bodies organized into chorus lines, all alike and moving in unison, arranged to look pretty? Is it not a way to dictate where they stand? A way to put them in their place?

To begin, an image – one that encompasses all the others. Serial girls are ancient history, and this image comes from the ancient Greeks. I am referring to the caryatids, those statues of women in tunics supporting an entablature on their heads and thereby acting as columns, pillars, pilasters. The name caryatids refers to the women found on the baldachin at the temple of Erechtheion, atop the Acropolis in Athens. Though they came to be known as caryatids, these figures were originally called korai, meaning virgins, maidens.10 But I prefer to stay within the interpretation proposed (and widely contested) by Vitruvius in De Architectura: the caryatids provide a pretext for a story that he proposes not as historical truth, but rather as an example of the kind of general culture architects should possess in order to carry out their work.

According to Vitruvius, the caryatids were erected in memory of the treatment the women of Karyae, a township in Sparta, suffered at the hands of the Greek invaders. After murdering all the men, the Greeks apparently made the women permanent figures of slavery so as to have them repay the debt of the city-state. Vitruvius’s interpretation is contested because statues of women draped in poplin and carrying an entablature existed before the period he discusses. However, what interests me here (regardless of the archaeological debates surrounding the origin and even the meaning assigned to these statues) is the contemporary reading the caryatids can elicit.

An architectural reading allows us to see them as the pillars of the building: remove the maidens and the structure collapses. They are foundations, as essential as the building material. Yet, what they are as well, essentially, is trapped. Though they support the temple’s roof, the caryatids are immobilized by and within the structure. They are, in fact, imprisoned.

What would happen if we imagined them moving? Were one of them to leave her place, the roof’s ensuing collapse would put all of them to death. They are dependent upon each other, in the same way that the structure of the Erechtheion requires their presence. Yet, how these women carry themselves – their draped tunics falling nonchalantly over their bodies, equidistant from each other, indifferent to their fate, perhaps even proud and powerful for carrying the roof of a temple – makes it possible to fantasize the other side of the enslavement coin. To go along with Camille Paglia, who enjoys fantasizing the caryatids’ feminism rather than studying them seriously:11 the temple’s roof appears to be floating above their heads, as if supported merely by their shared thoughts. Thus Vitruvius’s women are not enslaved widows so much as young women free and single; not held captive by their material surroundings so much as empowered by it and by their sisterhood. For these statues stand tall. And they form a collective.

Women-sentries, guardians of the temple. Women of desire we hope to see come to life….

Like the caryatids, serial girls are structural. After Vitruvius’s story, told in Roman times, the Erechtheion maidens’ motif was copied time and time again. Today, in our collective imagination, they join all the serial girls, who, like the caryatids in relation to the temple, are one of the touchstones of our social structure. Does the difference between the ancient Greeks and ourselves relate to the fact that in those days there was religion, the sacred, ritual, and myth supporting the belief system on which women’s station was determined? What remains of the link between the place occupied by women today and a system of beliefs that comes down to the part played by the media? And is the frenzy of media images, of technical reproduction, any worse than religious rites, or is it not just another mirror, another narrative of male domination?

Serial girls have forever been seen as pure decoration. They decorate: they function as accessories and jewellery, as friezes and other architectural ornaments. These details make the image and give the impression that there is nothing more innocent than desiring what is beautiful: women are beautiful, and they make an otherwise grey reality beautiful. But serial girls play a much more important role than that. More than decorative, they are central to the social structure; they are universal and essential, like the brick Gilbert Simondon discusses...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: I Is a Girl

- 1 Serial Girls

- 2 Young-Girl

- 3 Marginals

- 4 From the Latin Pupa: Poupée, Doll, Little Girl

- 5 Still Lifes

- 6 Fetish-Grrrls

- 7 DIM Girls

- 8 Tableaux Vivants

- 9 Like a Girl Takes Off Her Dress

- 10 Showgirls

- 11 Girl Tales

- 12 One for All, All for One

- 13 Mirror, Mirror

- 14 Bunnies

- 15 Blonds

- 16 Girls 1

- 17 Girls 2

- 18 Street Girls

- Conclusion: Firefly Girls

- Notes

- Backcover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Serial Girls by Martine Delvaux, Susanne De Lotbinière-Harwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminism & Feminist Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.