This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Mapping the First World War by Peter Chasseaud in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Primera Guerra Mundial. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Primera Guerra MundialChapter 1

The Causes of the War

Although the First World War was triggered by a local dispute between Austria–Hungary and Serbia, its origin was an existential struggle between empires. These empires were the German Second Reich, under Kaiser Wilhelm II; the Russian, ruled by Tsar Nicholas II; the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy, held together by Emperor and King (Kaiser und König) Franz Joseph II; and the Ottoman (Turkish), under Sultan Abdul Hamid II but with power increasingly in the hands of the ‘Young Turks’ of the Committee of Union and Progress. On the fringes at the outset, but drawn in by the system of alliances, were the Republican French and monarchical-democratic British Empires. While these two had been traditional enemies for reasons of proximity, religion, maritime and imperial rivalry, this enmity had faded in the face of the growing industrial, military, naval and manpower strength of Germany, which under Wilhelm II demanded its imperial ‘place in the sun’. France and Britain in any case both had their own quarrels with Germany. France burned for la revanche – revenge against Germany for the loss of the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine following the disastrous Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. Britain resented the deliberate challenge to the Royal Navy, her empire and her trade represented by Wilhelm’s building up of the Kriegsmarine, and also the vain posturing of this upstart grandson of Queen Victoria.

Position of the Fleet at Spithead on 24 June 1911. The British fleet during a Naval review at Portsmouth, shown on a special Admiralty Chart sold to the public for a shilling. It was after such a review, in July 1914, that the Fleet was dispersed by Winston Churchill to war stations.

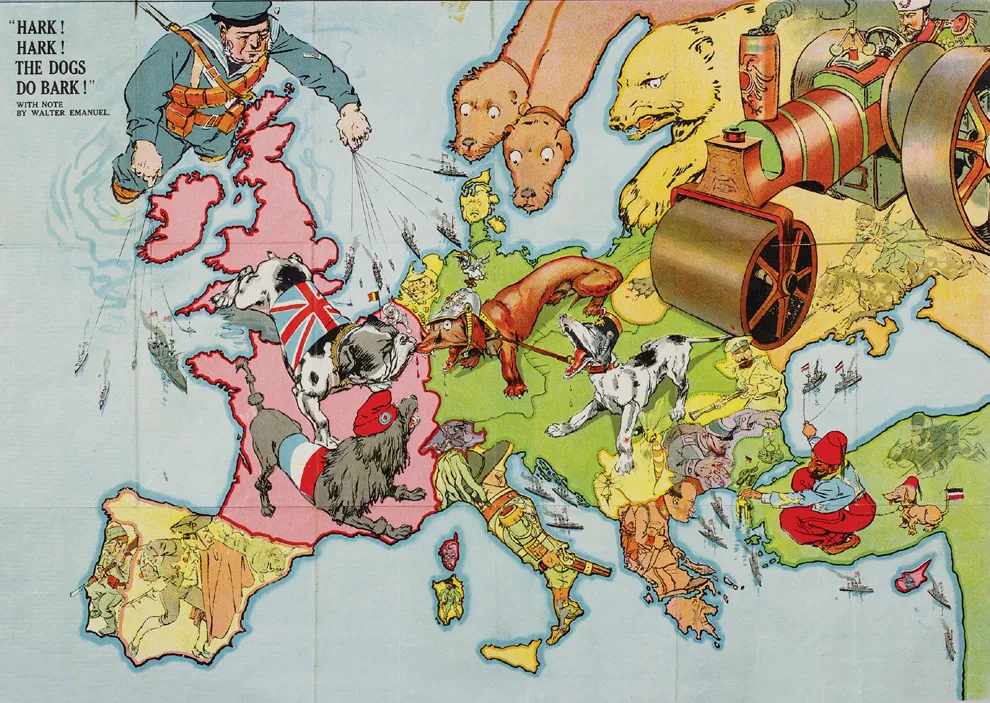

Hark, Hark! The Dogs do Bark.’ Poster-map showing Jack Tar, Russian Steamroller, French Cock, German Dachshund, etc.

The oppositional alliances had grown out of the fact that the German Reich’s increasingly aggressive stance in the late nineteenth century caused corresponding insecurity in France. When William I came to the throne of Prussia in 1860, he soon began to expand the army, which had hardly changed in size since the defeat of Napoleon. Prussia had become leader of the North German Confederation following her defeat of Austria in 1866, and the states of Hesse-Darmstadt, Württemberg, Bavaria and Baden were now obliged to support Prussia if called. In the 1870–71 war with France Prussia gained Alsace-Lorraine, and with the forces of these states she was able to field some 950,000 men. On the formation of the German Empire (in which Prussia and the Hohenzollerns were dominant) in 1871, it was written into the constitution that one per cent of the population could be in military training, and by 1914 Germany’s mobilization strength was about five million, with another five million untrained men.

In 1877 Germany brought Austria–Hungary and Italy into a Triple Alliance, and in 1890 France retaliated by creating an ‘Entente’ or defensive military understanding with Russia. Germany thereupon renewed, the following year, the Triple Alliance, and in 1899 rebuffed a mutual restriction of armaments proposed by the Tsar. The Franco-Russian Entente was augmented, in April 1904, by a new agreement between France and Britain, which ended centuries of mutual hostility and distrust. The memory of her unpopular war in South Africa against the Boers was fading, and Britain could no longer afford her splendid isolation in Europe. King Edward VII (‘Edward the Peacemaker’) had broken the ice in Paris, paving the way for an Entente Cordiale. Russia was no longer seen as a serious threat to the Indian Empire, indeed, having just been defeated by Japan, she was temporarily a broken reed, while Germany was now viewed as Britain’s major rival and threat. France, needing to look elsewhere for support, turned to Britain. The Entente Cordiale developed into the Triple Entente, incorporating the Franco-Russian and a new Anglo-Russian Entente.

A detail from Karte des Weltkrieges [Map of the World War]

While Belgium was not part of the system of alliances, her neutrality was guaranteed by the Treaty of London of 1839 and she was a significant imperial power. King Leopold II’s greed for the acquisition and brutal exploitation of economic resources (notably ivory and rubber) and territorial expansion (notably his close involvement in the murderous ‘Congo Free State’) was instrumental as a catalyst in the great European ‘scramble for Africa’ in the late nineteenth century. The Berlin or Congo Conference of 1884–5 formalized and regulated the ‘new imperialism’ process of trade and colonization in Africa, and marked an acceleration of European colonial activity.

The pressures and tensions of political and economic competition and rivalries among the European powers after 1870 were reflected and contained by their transfer to a new site of conflict – Africa. The powers saw an orderly partition of Africa as a means of avoiding war with each other over African territory and resources. The old methods by which the European powers maintained hegemony through ‘informal imperialism’ – missionaries, military expeditions and economic penetration – gave way to outright colonization involving military occupation, annexation, administration and an enforced new economic and trading paradigm.

Origins of the War

Historians sometimes attempt to disentangle the many proximate and more distant causes of the First World War by categorizing them as structural ‘grand causes’ on the one hand, and contingent causes on the other. In the first ‘grand’ category they place familiar and inter-related features of the pre-war world such as its nationalism, imperialism (attempts to maintain hegemony, competition and the scramble for colonies and empire) and economic rivalry (the struggle for markets) and the arms race, the networks of alliances which strove to maintain a balance of power, the nature of elite groups within nations (and also international elites), the structures of diplomacy, and the primacy of domestic policies which meant that international issues came to be used for internal purposes. In the second, or ‘contingent’ group they might include a country’s or region’s political history, focusing on the importance of individual agency and psychology (for example the character of the German Kaiser), the nature of the decision-making process by tiny coteries of statesmen, dominant ideology and mass psychology, and cultural traits and habits. To these two main categories could also be added ‘events’, or immediate causes. This is all to say that the causes were, as usual, multifarious and complex, and, whether they are theorized in terms of group conflict, games theory (rational strategies) or something else, have to be reduced here to something easier to grasp and apply.

The World, Showing German’s Peaceful Penetration (German Empire, green; What Germany Wanted, yellow), c.1920. An example of post-war anti-German propaganda, showing Germany’s economic, trading, financial, trading, missionary and other activities.

The First World War, or Great War as it was known until twenty years later when the second such conflict grew out of the peace treaties intended to resolve the first, was initiated by the explosion of the Balkan ‘powder keg of Europe’. The long and complex intertwining of national liberation struggles against Ottoman (Turkish) imperial overlords in the Balkan peninsula with the interference and intrigue of European nation states provided the slow-burning fuse which eventually blew this mine and tore apart the map of Europe and its empires.

A detail from Karte des Weltkrieges [Map of the World War], showing German and other colonies in Africa. The inset shows Germany drawn to the same scale.

A hand-written annotation on the reverse of the map shown on the right to the effect that this was one of several maps relating to the ‘nationalities’ question, used by British Military Intelligence, while preparing for the peace conference at Versailles: ‘used in determining Propaganda campaign and the redistribution of territory after the War on the principle of self-determination.’

Ethnographical Map of Central and South Eastern Europe, prepared by the War Office in 1916.

The danger, the great ‘what if?’, had long been recognized, to the extent that it had been given a specific name – the Eastern Question. This question was: how could the European powers, including Russia, control the volatile and unpredictable business of national insurgence and emergence in the Balkans, in the context of a weakening Ottoman empire, without the whole process spinning out of control? How to manage the evolving situation so as to maintain national interests, without disturbing European stability and precipitating serious conflict? Perhaps, in games-theory terms, there were ultimately too many variables at work, too many fragile egos, too much emotion, too many sensibilities, perhaps too much autocracy and too little democracy, for stability to be maintained. And conflict management can only work with the consent of the parties concerned.

But other questions remain to be asked: if the Great Powers were able to ‘manage’ the First and Second Balkan Wars, which took place in the years immediately prior to the outbreak of war in 1914, why were they unable to control the Third? And why did this new conflict grow not just into a European War but into one of global reach? Of course, there were other factors at work in the decades before 1914 which were calculated to increase international tension, not least the three related ones of escalating industrial, imperial and naval rivalry, and also modernization, demographic and resource stresses.

Starting as a Third Balkan War, it exploded into a pan-European conflict that, because of the global imperial expansion of several European states before the war, soon spread across the world. For various reasons, the conflict brought in certain European states that were not initially involved. Some, like vultures, hovered on the sidelines waiting to pick over the corpse of empires and defeated nations, while others just waited to join the winning side. Yet more, like Switzerland, Spain, Norway and Sweden, remained neutral throughout.

During the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire slowly crumbled. Turkey was known as the ‘sick man of Europe’, and indeed at the start of that century still held large territories on the European side of the Bosphorus. Assisted by the Great European Powers, independent states were created on the principle of nationality, replacing the rule of the Ottoman sultan. Greece was the first. The Turks had dominated the Balkan peninsula since they had overrun the Christian Byzantine Empire in the second Islamic campaign (or jihad) between the eleventh and seventeenth centuries. The capital of Byzantium, Constantinople (Istanbul), had fallen to them in 1453, and their armies had unsuccessfully besieged Vienna in 1529 and 1683. Ever since the fall of Constantinople, foreign powers had proposed schemes to end Turkish domination of the Balkans, but it was only when waxing Christian states began to put the Ottoman Empire on the defensive that these plans became at all significant.

Two predatory European states were the initial players in this game – Austria and Russia. After 1699, Austria conquered Hungary and Croatia, while Russia expanded southwards towards the Black Sea. By 1774, Russia had gained control of the Black Sea by destroying the Turkish navy in a long-drawn-out war. She insisted on treaty rights to intervene in Ottoman affairs to ensure ‘orderly government’ in the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, and to act as ‘protector’ of Turkey’s Christian subjects.

It was, however, Poland, always a prime contested area in eastern Europe, rather than Turkey, that was the ultimate victim of the aggression of Austria and Russia. In their conquest and partitions of Poland at the end of the eighteenth century, they were assisted by Prussia, another militaristic and autocratic state whose star was in the ascendant. Joseph II of Austria and Catherine the Great of Russia now planned to partition the Balkans. In this scheme, Austria would have Bosnia and Herzegovina, and part of Serbia, Dalmatia and Montenegro, while Russia would take the rest, which included Greece. Catherine’s overarching idea was to make her grandson – the deliberately named Constantine – the ruler of a reconstituted Byzantine Empire in Constantinople. Catherine was prevented in this ‘Greek Project’ by the other Great Powers. Britain in particular, having gained an important foothold in India, was becoming concerned about Russian expansion and her possible domination of the Bosphorus, the Straits separating Europe from Asia, and the Mediterranean. Stymied in her advance on Byzantium, Catherine gobbled up the Crimea instead.

Austria and Russia, ruled by ‘enlightened despots’, had no interest in fostering national independence movements in the Balkans. Rather, they sought to replace the rule of the Islamic sultan by their own Christian imperial rule. The sprawling, polyglot and ethnically diverse Habsburg and Russian Empires were, as they became increasingly aware during the nineteenth century, vulnerable to the doctrines of romantic nationalism and self-determination. Following the Napoleonic Wars, the Habsburgs were intensely suspicious of and hostile towards the Slav liberation struggles on their Balkan doorstep, which they perceived to be threatening the cohesion of their empire. Their role was, rather, to keep their subject peoples Kaisertreu – loyal to the emperor. The Russians, however, fostering pan-Slavism, saw themselves as supporters of Orthodox Christianity against the Islamic Turks.

Turkey in Europe and Greece, from The Advanced Atlas, engraved by John Bartholomew, FRGS, William Collins, Sons, & Company, 1869, showing the extent of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans at this date.

The ‘age of enlightenment’, the American War of Independence, and the French Revolution with its Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, and the example of Napoleon, changed not only the intellectual but also the political map of Europe and the world. Rights and nationalism proved a potent brew. Article III of the Declaration of the Rights of Man (1789) s...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- The Map Collection of the Imperial War Museums

- Contents

- Introduction - Mapping in the First World War

- Chapter 1 - The Causes of the War

- Chapter 2 - The 1914 Campaign in the West and the East

- Chapter 3 - Italy, Gallipoli, Macedonia, The Caucasus

- Chapter 4 - Egypt and Palestine, Mesopotamia, Africa

- Chapter 5 - The 1915 Campaign in the East and the West

- Chapter 6 - The 1916 Campaign in the East and the West

- Chapter 7 - The War at Sea and in the Air

- Chapter 8 - The 1917 Campaign in the East and the West

- Chapter 9 - The 1918 Campaign in the East and the West

- Chapter 10 - The Peace Treaties and their Aftermath

- Glossary

- Further Reading

- List of Maps and Aerial Photographs

- Index

- Acknowledgements

- Photograph Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher