eBook - ePub

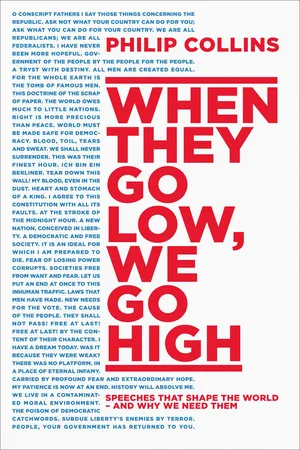

When They Go Low, We Go High

Speeches that shape the world – and why we need them

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access When They Go Low, We Go High by Philip Collins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Collections. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Democracy: Through Politics the People Are Heard

The Best State of the Commonwealth

Good politics is founded on extraordinary hope. Political imagination is the fancy that the world can get better and that the actions of men and women can together make it so. That act of utopian imagination is a description of democratic politics at its best. It is heard to great effect in the words of Marcus Tullius Cicero, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy and Barack Obama. This is where we hear the idea of popular power expressed in language lifted to move the people. It is politics enchanted once again.

One of the flaws of liberal democracies is that, when they succeed, they start to sound boring. Over time, power has a tendency to corrupt language, though not because politicians are venal. It is because success turns a politician from a campaigner into a technocrat. Their speeches – and I plead guilty to writing some of them – become one half braggadocio about achievements to date and one half technical exposition on policy detail. The enchantment goes missing and so does utopian hope.

Half a millennium ago, in 1516, Thomas More published a strange and remarkable volume called Utopia. Oddly, for a man with a deserved reputation for severity, a lifelong wearer of a hair shirt, More was fond of jokes, and the title of his most famous book is a tease. Does he mean eutopia, the good place, or does he mean outopia, no place at all? He adds to the sense of play by giving his narrator the name of Raphael Hythloday, which translates from Greek as ‘speaker of nonsense’. More’s text causes us to ponder whether Utopia is his version of the perfect society or a kind of Tudor cabaret act.

The clue to the riddle is also the link between Cicero and the rhetoric of the American republic, and it is found in More’s subtitle Optimus status republicae: ‘The Best State of the Commonwealth’. Or to put it in a current idiom, the perfect state of the union. More sends his narrator Hythloday on a journey to Utopia where he discovers, ready-made in the ocean, a society that dramatises Cicero’s argument for the Roman republic. That argument, which More revives and which Jefferson, Lincoln, Kennedy and Obama all articulate, is how the people are to be heard. More’s answer to that question is politics. The noble life, he argues, is one that is dedicated to public service in the name of the people. This marks a change from the Greek tradition in which it was thought that a citizen had to be of noble birth. Cicero’s argument is that virtue, rather than inherited wealth, should have its reward. It is in the finest speeches about popular power that this idea is expressed.

But it is not just the beauty of the idea that makes these speeches fine. The beauty of the diction counts too. Fixing problems is the purpose of democratic politics but saying so is never enough. As La Rochefoucauld said, ‘the passions are the only orators that convince’. Democratic politics still needs the elevation of Cicero’s case for the Roman republic, Thomas Jefferson’s praise of the blessing of equal liberty for all, Abraham Lincoln’s ability to summarise the promise of democracy in a single phrase, John F. Kennedy’s call for an active citizen body and Barack Obama’s extraordinary, audacious hope. All these speakers express in unforgettable cadences the political virtue of granting power to the people.

But, in our time, an alternative utopia to liberal democratic politics has risen again in the form of populism. If politics is to turn away from this phoney appeal to the people, it can only do so in words that once again resound to the times. If politics has become dry then it needs to be reinvigorated by the precious democratic gift represented by the principle of hope.

Popular politics cannot work without utopian spirit. We need to draw from More’s Utopia its sense of possibility, because the spirit of utopia is a desire for progress. It is a way of thinking that reminds us that the world might be different. This hope needs to be expressed in words that take wing. Rhetoric is the art of public persuasion, and if the ideas of liberal democracy are to retain their hold over the imagination of the people, they need to be argued with clarity and elevation. In the speeches that follow, they are.

MARCUS TULLIUS CICERO

First Philippic against Mark Antony

The Senate, the Temple of Concord, Rome

2 September 44 BC

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BC) was the first man to claim that rhetoric can save the state. Cicero was a philosopher, politician, lawyer and writer. He was the first among equals of the rhetoricians, both as a speaker himself and as the man who made the subject a systematic field of study. Cicero’s De oratore is still the best rhetorical instruction manual. He is headmaster of the school of oratory.

Cicero’s five canons of rhetoric still work; they will always work. Invention, he says, is the drafting of good arguments; disposition is the arrangement of those arguments for best effect; style is giving the argument shape in language; memory is recall in an age before autocue; pronunciation is delivery on the day. Cicero also identified three styles. The plain style should be used to teach, the ornate middle style to please, and the grand style to arouse the emotions. But De oratore was more than a book of instructions on how to talk. It was a book of statecraft as well: the subjects were for Cicero indivisible. If rhetoric and democracy were born together with Pericles, then rhetoric and statecraft were united by Cicero.

After a spell as a slum landlord, Cicero devoted his life to the theory and practice of oratory. He learned his trade in Rome under the tutelage of Crassus, the leading orator of his day. Cicero was debarred from a career in politics due to his ignoble plebeian ancestry. He grew up in the provincial town of Arpinum, the son of a fuller, a cloth-maker who soaked wool in urine for cleansing purposes. Cicero instead built a reputation as a lawyer of great integrity and gained public recognition when he acted in the impeachment of the corrupt governor Gaius Verres in 70 BC. Low birth notwithstanding, he did then make it into politics. In 63 BC he exposed a plot by Lucius Sergius Catiline to launch a coup against the Roman republic. The Orations against Catiline are the most ferocious tirades against a rival in the history of speech. The story is told, fictionalised to dramatic effect, in Robert Harris’s trilogy of historical novels about Cicero.

When Cicero said of Catiline in the Temple of Jupiter: ‘Among us you can dwell no longer’, he ended Catiline’s career. But he also damaged himself. Cicero was granted the title of Pater Patriae, Father of the Fatherland, but he was exiled from the republic for having, in the aftermath of triumph, executed a Roman citizen without trial. The law of the republic made no exceptions, even for its saviour.

It is to the curatorial brilliance of Cicero’s devoted secretary Tiro that we owe the fifty-eight Cicero speeches, of the eighty-eight we know he gave, that we have today. We also know Cicero from his letters to Atticus, which were discovered by Petrarch in 1345 and which are the source of the influence that Cicero was to have on the European Renaissance. In the decade of his retreat after fleeing Rome in 55 BC, Cicero composed a series of works that have among their debtors the significant names of Hobbes, Locke, Voltaire, Montesquieu, Burke, Adam Smith and Rousseau.

The speech that follows was delivered in the wake of the slaughter of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC. Cicero had been no supporter of Caesar’s tyranny but, mindful that the republic was bigger than any ruler, he had negotiated a settlement in which Caesar’s late decrees would be honoured. The consul Mark Antony confirmed that he would consent, but then, at Caesar’s funeral, seemed to renege on the commitment by inflaming public opinion against the conspirators. Cicero fled the city, disillusioned at the decline of the republic, but returned, to be greeted by multitudes in the streets. The next day, rather than turn up at the Senate to hear Mark Antony, he pleaded fatigue. The Senate met again a day later, when Cicero delivered this speech.

We know it now as the first in a series of fourteen venomous speeches directed at Mark Antony. In a knowing reference to Demosthenes, who, between 351 and 341 BC, tried to rouse the Athenians against the threat of domination by King Philip II of Macedon, Cicero referred to these speeches as ‘Philippics’. Lest this be thought too much invective to be spent solely on Mark Antony, remember that Cicero’s true purpose was to save the republic. In the Second Philippic, published as a pamphlet rather than spoken, Cicero compares Mark Antony with Catiline. The series then leads towards the explicit conclusion of the Fourteenth Philippic that Mark Antony was the enemy of the people and a threat to the republic. When politics fails, the only option, Cicero warns, is discord. The Philippics are the high point of Cicero’s career. In his fledgling years he had been full of ingenious phrases searching for an appropriate cause. Twenty years before, the Catiline conspiracy had given him his first great moment. The Philippics are his glorious second act. All at once his verbal fluency rhymed with the times.

Before, O conscript fathers, I say those things concerning the republic which I think myself bound to say at the present time, I will explain to you briefly the cause of my departure from, and of my return to the city. When I hoped that the republic was at last recalled to a proper respect for your wisdom and for your authority, I thought that it became me to remain in a sort of sentinelship, which was imposed upon me by my position as a senator and a man of consular rank. Nor did I depart anywhere, nor did I ever take my eyes off the republic …

The opening of a speech, like the first still in a film, should contain the address in miniature. Cicero here defines his Topic: the future of the republic. He gets to the main point quickly, as all speakers ought. The point is the defence of the republic and the liberty of the people against those, the tyrants Caesar and Mark Antony, who would violate its principles. This is rhetoric about crisis which increases the crisis with each utterance. Note how Cicero establishes his credentials as sentinel, senator and consul, which give him standing in the republic. He does this to justify his intervention in a dispute from which he has been absent.

The stakes are high, hence Cicero’s dramatic language. The conspirators against Caesar knew, and Cicero himself knew, that his voice in the Temple of Concord could be decisive. Defeat would probably mean death. There is also a personal frailty on display. Cicero had at first struggled to break into politics because his family were plebeian rather than patrician. If he sounds more than a little defensive, ostentatiously reading out his curriculum vitae, this is why. He also has a material reason for defending his calling. The republic thrives on argument; dictatorship would banish his skill. Cicero’s standing as a man of repute rests on the credentials he begins with and the mastery of argument that he commands.

I declare my opinion that the acts of Caesar ought to be maintained; not that I approve of them (for who indeed can do that?) but because I think that we ought above all things to have regard to peace and tranquillity. I wish that Antonius himself were present, provided that he had no advocates with him. But I suppose he may be allowed to feel unwell, a privilege he refused to grant me yesterday. He would then explain to me, or rather to you, O conscript fathers, to what extent he would defend the acts of Caesar. Are all the acts of Caesar that may exist in the bits of notebooks, and memoranda, and loose papers, produced on his single authority, and indeed not even produced, but only recited, to be ratified? And shall the acts he caused to be engraved on brass, in which he declared that the edicts and laws passed by the people were valid for ever, be considered as of no power? I think, indeed, that there is nothing so well entitled to be called the acts of Caesar as Caesar’s laws.

This speech registers Cicero’s deep disapproval of the way in which Mark Antony is squandering Caesar’s legacy. Cicero dismisses Mark Antony with bitterly feigned generosity about the privilege of being deemed unwell. Later passages in this Philippic make it clear that Cicero’s absence the previous day had been as pointed as Antony’s is today. Cicero therefore hardly deserves the high moral ground on which he stands to make his central accusation that Antony is betraying the legacy of Caesar. Framed as a battery of rhetorical questions – always a tactic to sound reasonable while delivering a vicious blow – Cicero here fatally undermines Antony’s claim to be the guardian of Caesar’s legacy. Later in the speech Cicero bluntly accuses Mark Antony of ‘branding the name of the dead Caesar with everlasting ignominy, and it was your doing – yours I say’.

The vivid passage about the notebooks shows how a good image adorns an argument. An audience gets only one hearing, and pictures dwell longer in the mind than abstract arguments. As Cicero describes them, we can see the contents of Caesar’s office. This is the only time Caesar is depicted as a person rather than a representative of the lost republic. The image has a brutal purpose. Cicero is insinuating that Antony is abusing his access to Caesar’s private papers, entrusted to his care by Caesar’s widow. Cicero requests that Mark Antony supply an explanation, not to himself but to the fathers of the republic. That act of transference identifies his own status and perspective with that of the wider republic itself.

And yet, concerning those laws that were proposed, we have, at all events, the power of complaining; but concerning those that are actually passed we have not even had that privilege. For they, without any proposal of them to the people, were passed before they were framed. Men ask, what is the reason why I, or why any one of you, O conscript fathers, should be afraid of bad laws while we have virtuous tribunes of the people? … The forum will be surrounded, every entrance of it blocked up; armed men placed in garrison, as it were, at many points. What then? – whatever is accomplished by those means will be law. And you will order, I suppose, all those regularly passed decrees to be engraved on brazen tablets. ‘The consuls consulted the people in regular form’ – (is this the way of consulting the people that we have received from our ancestors?) – ‘and the people voted it with due regularity.’ What people? That which was excluded from the forum? Under what law did they do so? Under that which has been wholly abrogated by violence and arms? But I am saying all this with reference to the future, because it is the part of a friend to point out the evils that may be avoided; and if they never ensue, that will be the best reflection of my speech. I am speaking of laws that have been proposed, concerning which you have still full power to decide either way. I am pointing out the defects; away with them! I am denouncing violence and arms; away with them, too!

There are direct and deliberate echoes of the Philippics of Demosthenes throughout Cicero’s speeches against Mark Antony. Rhetoric, even at this early stage, is already a tradition. We can see this first at the level of style. Cicero’s interest in Demosthenes was a reaction to a movement of orators in Rome known as the Neo-Attics, who criticised the elder statesmen, of whom Cicero was the sovereign example, of being stylistically weighed down by decoration. The criticism, that Cicero was, to use the contemporary term, an “Asiatic” orator, was always unfair; Cicero never set much store by purple prose. He insisted that a sentence needed rhythm rather than the ‘embroidery’ he found in some Greek examples, notably the work of Gorgias. The Philippics are, though, plainer in style than Cicero’s previous work.

Not having a style is, of course, a style of its own. ‘I am no orator, as Brutus is, but as you know me all, a plain, blunt man, that love my friend,’ says Antony in Julius Caesar, which is about as rhetorically effective as it gets. The Philippics do not, by the standards of the day, set off many fireworks. They are exact and precise, perhaps to a fault, and they are rather light on memorable imagery. The picture of Antony’s wife Fulvia, in the Second Philippic, with the blood of innocent soldiers splashed on her clothes, is exceptional. For the greater part, the series is forensically argued.

There are also echoes of Demosthenes in Cicero’s argument. Both profess that liberty is in peril, threatened by a dominant individual whose seizure of arbitrary power must be resisted. This is a threat to peace because, as Cicero argues later, peace follows liberty. Both Cicero and Demosthenes before him were seeking to persuade a divided and hesitant audience to take action. There is a choice for both between self-government and tyranny, between true peace and illusory peace, between liberty and slavery.

What I am more afraid of is lest, being ignorant of the true path to glory, you should think it glorious for you to have more power by yourself than all the rest of the people put together, and lest you should prefer being feared by your fellow citizens to being loved by them. And if you do think so, you are ignorant of the road to glory. For a citizen to be dear to his fellow citizens, to deserve well of the republic, to be praised, to be respected, to be loved, is glorious; but to be feared and to be an object of hatred, is odious, detestable; and moreover, pregnant with weakness and decay.

This short section is a clear definition of the philosophical tradition of the Roman republic. This is the argument that was passed down from the classical world to the European Renaissance. The esteem in which Cicero is held is satirised by Erasmus in his 1528 treatise Ciceronianus, written in the form of a dialogue, which contains a character who has emptied his library of all books except those by Cicero.

The idea of the Roman republic begins with the fact that the central goal of the city was peace. The greatest danger to peace, says Cicero, is discord. The setting for this speech is the Temple of Concord, but how is concord to be attained? Concord requires justice for all, and that can only be achieved if all the citizens live in liberty. There can be no freedom except in a republic, and the citizen of the free republic is the engaged man, the political man. This is an echo of an argument Cicero uses in De re publica, where he suggests that political participation can overcome the constant dangers of complacency, ‘the blandishments of pleasure and repose’.

The law of the republic is a vital institution, but Cicero argues that the actions of those who will defend the republic, even to the extent of murder, are legitimate all the same because they uphold the honour of the republic. The story goes that when Caesar was murdered on the Ides of March in 44 BC by a group of senators who called themselves the liberatores, one of their number lifted his bloodstained dagger and cried out the name of Cicero, imploring him to ‘restore the republic!’ Cicero’s primary objective in the speech was therefore the restoration of the res publica libera – the free republic.

And, indeed, you have both of you had many judgements delivered respecting you by the Roman people, by which I am greatly concerned that you are not sufficiently influenced. For what was the meaning of the shouts of the innumerable crowd of citizens collected at the gladiatorial games or of the verses made by the people? Or of the extraordinary applause at the sight of the statue of Pompeius? And at that sight of the two tribunes of the people who are opposed to you? Are these things a feeble indication of the incredible unanimity of the entire Roman people? What more? Did the applause at the games of Apollo, or, I should rather say, testimony and judgement there given by the Roman people, appear to you of small importance? Oh! Happy are those men who, though they themselves were unable to be present on account of the violence of arms, still were present in spirit, and had a place in the breasts and hearts of the Roman people.

It is evident from this first Philippic that Cicero is vying to be the leader of the political opposition. Look at how brazenly he enlists the audience in his cause. In mocking Mark Antony’s deafness to popular opinion, Cicero casts himself as the tribune of the people. It is a reminder that the verdict on a public speech in a democracy is settled by the audience. This is an indispensable lesson for every speaker, at every level. It’s not, in the end, you who decides whether a passage works. The audience will decide for you.

Mark Antony reacted with fury to the accusation that he disdained his audience, and seventeen days later delivered a withering attack on Cicero’s career in the Senate. Cicero did not attend because his safety could not be guaranteed. Fearful for his life, he published the Second Philippic as a pamphlet and issued instructions through his friend Atticus for it to be circulated carefully and narrowly. The Second Philippic is written as thou...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Speeches

- PROLOGUE: The Perils of Indifference

- CHAPTER 1: Democracy: Through Politics the People Are Heard

- CHAPTER 2: War: Through Politics Peace Will Prevail

- CHAPTER 3: Nation: Through Politics the Nation Is Defined

- CHAPTER 4: Progress: Through Politics the Condition of the People Is Improved

- CHAPTER 5: Revolution: Through Politics the Worst Is Avoided

- EPILOGUE: When They Go Low, We Go High

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

- About the Publisher