![]()

1 Blues and roots

(jazz before 1920)

The spread of jazz in the first two decades of the twentieth century is astounding, given the technological limits of the time. On the basis of a few phonograph recordings, some piano rolls and the wanderlust of early jazz musicians, a style of music that was spawned primarily in black communities of the American South had spread across the country and begun to make inroads around the world. Jazz was already starting to signify freedom and forward thinking, and it would soon lend its name to a euphoric period that saw other musical styles redefined by its feeling and beat.

Roots and routes

There were no audio recordings of jazz before 1917, so we have to turn to other forms of evidence to discover how jazz took shape before 1920 – what we could call the music’s prehistoric period.

must know

Jazz historians usually rely on sound recordings, but for the years prior to 1917 they have had to resort to other evidence, such as accounts passed down by those who heard the music firsthand.

Jelly Roll Morton left piano rolls that offer suggestions of how early jazz sounded.

Even after the startling success of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band’s ‘Livery Stable Blues’ and ‘Dixieland One-Step’ – the first jazz 78 rpm recording and a million-seller upon its release in 1917 – recording companies remained more interested in classical artists and more polite dance orchestras.

The rolls of paper cut by seminal figures like Scott Joplin and Jelly Roll Morton for use in player pianos also provide only limited insight; they fail to capture nuances of touch and accent. Also, in a precursor to the overdubbing of later decades, piano rolls often contained added parts that made the resulting music almost impossible to play by a single pianist.

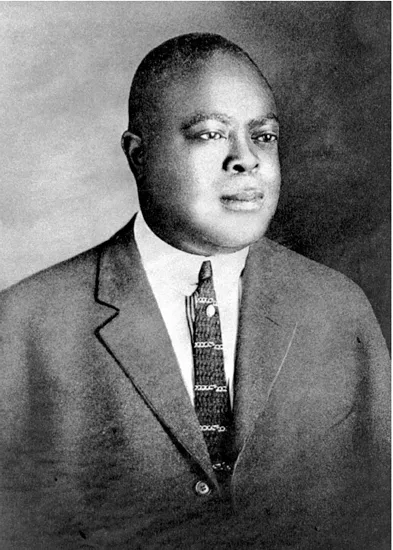

Morton and Joseph ‘King’ Oliver began to record in 1923, but jazz developed at such a rapid pace in this period that the music did not necessarily reflect what these and other artists sounded like 10 or 20 years earlier. Many witnesses who lived in New Orleans and were familiar with the music played there during the 1897–1917 heyday of the city’s infamous Storyville district insisted that the first recordings by Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band represent a significant evolution from his earlier style. Some even swore that the real sounds of Storyville were never captured on recordings.

In the soundbite version of jazz’s origins, rhythmic African music and harmonic European composition merge in the black and Creole neighborhoods of New Orleans, taking root there and then migrating north and east by riverboat just prior to the 1920s. But this capsule creation myth glosses over a far more complex and widespread history. When Morton, Oliver and their peers began to develop what the world came to know as jazz, they were able to draw upon nearly a century of African-influenced musical styles developed all over America and the Caribbean. And many of these innovators didn’t wait for the shutdown of New Orleans’s red light district, or the next paddle wheeler leaving from the local port, to take what they had learned on the road.

Cornetist Joe ‘King’ Oliver was one of the first jazz pioneers to record his music – but not until 1923.

Africa

Africa was an essential source point for jazz music, inspiring such key jazz elements as rhythmic expression, improvisation, call-and-response and narrative techniques, and interactive spirituality.

did you know?

The banjo, a prominent instrument during jazz’s early years, originated in Africa.

In Africa, unlike Europe, rhythm served as the primary element of musical expression, and ensembles composed entirely of percussion instruments created extended polyrhythmic works. African music was not committed to paper; it was an oral (or more accurately an aural) tradition, learned by ear and therefore more naturally subject to spontaneous variation. Techniques such as call-and-response patterns, where a lead voice is answered by the surrounding ensemble, and narrative forms such as the insult-laden songs of allusion from West Africa would reappear as central components of the jazz style.

Africa fed jazz with rhythmic and formal inspirations, and even with an instrument in the case of the banjo.

Religious music

The power of African musical ideas was felt in the Western Hemisphere long before 1900, and far beyond the confines of a single community. Africa influenced evolving styles of religious music, at first through the survival of vodun (voodoo) societies in Catholic portions of the New World, where European religious practices were less likely to be imposed upon the slaves than in the Protestant American South. This gave African religious music a foothold in New Orleans, where the slaves were allowed to dance and play instruments in Congo Square beginning in 1817, as well as in Cuba and Haiti.

Traces of African influence were also entering Christian religious practice. Camp meetings and revivals, popular in rural and frontier America during much of the nineteenth century, frequently featured black preachers who preached in a florid, interactive style that was at times similar to the trancelike states of the vodun societies and anticipated the congregational fervour of later gospel services.

A more formal merger of African and European musical influences led to circle dances or ‘ring shouts’, which were first described in the Civil War period. In these musical expressions, improvised variations on short, rhythmic melodies (later called ‘blue notes’) were created through call-and-response patterns. Concert performances of Negro spirituals, which became popular after the first tour of the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1871, are another example of the African/European synthesis.

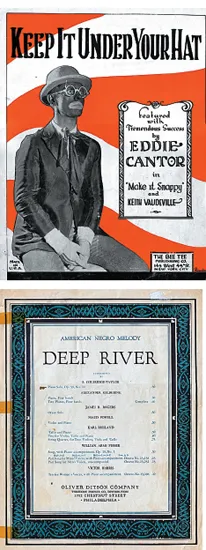

The influence of nineteenth-century minstrelsy and spiritual singing resonated into the following century.

Minstrel shows

American secular music was also showing the influence of Africa in a variety of ways. During the last half of the nineteenth century, minstrel shows were the most popular form of entertainment throughout the country. They presented a caricature of Negro life that lingered until the civil rights era of the 1960s. Minstrel shows mixed dramatic vignettes and vaudeville acts performed by Caucasians in blackface like the popular Thomas D. ‘Daddy Jim Crow’ Rice. They featured stylizations of black music by white composers like Stephen Foster. The shows were a two-edged sword, stereotyping and stigmatizing the manners of the former slaves while also spreading their culture and subtly mocking the mainstream.

did you know?

The cakewalk, a popular dance craze that formed the centerpiece of many minstrel shows, originated on plantations in the American South with slaves who mocked their masters’ behaviour.

Ragtime and blues

As more sophisticated, spontaneous – even revolutionary – styles of African American music arose, minstrel shows helped disseminate them to audiences around the country. Two such styles, which we can consider jazz’s siblings rather than its strict chronological precursors, were ragtime and blues.

did you know?

When Jelly Roll Morton made his invaluable Library of Congress recordings in 1938, he used Joplin’s ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ to illustrate how ragtime had generated – and then been superceded by – the new jazz approach.

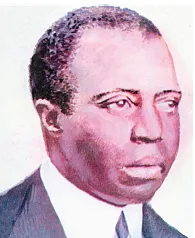

Scott Joplin’s ragtime compositions for solo piano created a phenomenon at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Ragtime

Ragtime was initially a midwestern phenomenon. The style initially became identified with St Louis, Missouri, where Scott Joplin and other itinerant pianists gained initial fame near the turn of the century, and it quickly turned into a popular fad with the rise of the cakewalk. The music is totally composed, with distinct sections usually of 16 bars that suggest a classical rondo. But ragtime’s defining characteristic is its staggered, ragged, syncopated melodies that place accents on unexpected beats and create a momentum anticipating...